The Rise of Fake News

American democracy faces a crisis: media trust collapsed along partisan lines as journalism became a profit-driven commodity rather than public service. The 1987 repeal of the Fairness Doctrine and rise of social media algorithms shattered shared reality citizens need for self-governance.

The Collapse of Shared Truth: How the Destruction of Public Interest Media Broke American Democracy

Central Argument

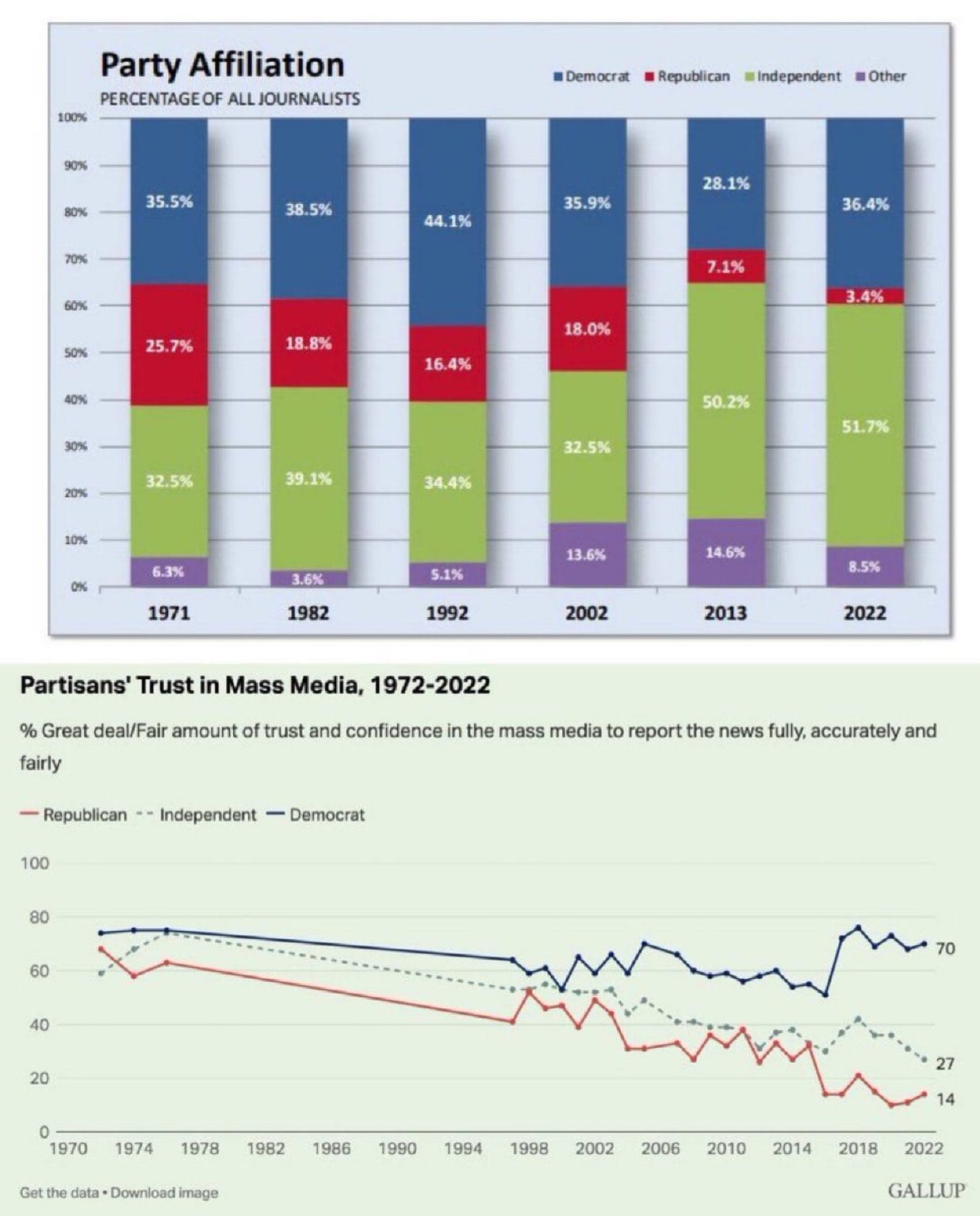

America faces a crisis of truth. Between 1971 and 2022, Republican journalists nearly disappeared from mainstream media, dropping from 25.7% to just 3.4% of the profession. During the same period, trust in media collapsed along party lines. By 2022, 70% of Democrats trusted mass media while only 14% of Republicans did. This is not just political disagreement. This represents the breakdown of a shared reality that democracy requires to function.

The root cause is structural: journalism stopped being treated as a public service and became a profit-driven product. When Ronald Reagan's Federal Communications Commission repealed the Fairness Doctrine in 1987, it marked the moment when neoliberal ideology officially transformed American media from a civic institution into a marketplace commodity. Combined with the rise of social media algorithms designed to maximize engagement rather than inform citizens, this shift has shattered the common ground Americans need to govern themselves.

Part I: Two Americas, Two Realities

Modern America is split into separate information worlds. The numbers show this division clearly. In 2022, Democrats and Republicans did not just disagree about politics. They disagreed about basic facts. Seven out of ten Democrats said they trust mass media to report news accurately and fairly. Only one out of seven Republicans said the same. Independents fell in between at 27%.

This is not normal political disagreement. Throughout the 1970s, roughly 70% of Americans across all parties trusted the news media. Democrats, Republicans, and Independents all watched the same evening news broadcasts and read the same newspapers. They argued about what to do with shared information, not about whether the information itself was real.

The journalist data reveals why this trust fractured. Modern newsrooms have become politically lopsided. Republicans made up more than one in four journalists in 1971. By 2022, they were less than one in twenty. This did not happen because news organizations banned conservatives. It happened because journalism became embedded in cultural and economic environments that naturally select for certain worldviews.

Journalism jobs moved to expensive coastal cities. The profession required expensive college degrees. Newsrooms developed cultural norms that fit urban, educated, socially progressive settings. Conservatives did not feel pushed out by explicit rules. They simply found themselves in spaces where their perspectives seemed out of place. The profession reproduced itself through cultural fit rather than deliberate exclusion.

Part II: From Public Service to Market Product

Understanding this crisis requires looking at how American media once worked. During the 1970s, news operated under different rules. The Fairness Doctrine, established in 1949, required broadcasters to cover controversial public issues and present contrasting viewpoints. Television networks ran news divisions as prestige projects, not profit centers. Journalism schools taught objectivity as a core value. Local newspapers maintained diverse voices and served as community forums.

This system had serious flaws. It excluded many voices, especially from marginalized communities. It often deferred too much to government and corporate authority. But it created something crucial: a baseline shared reality. Americans could fight over what policies to support while agreeing on underlying facts.

The Neoliberal Revolution and the Death of Public Interest Broadcasting

The transformation began with a fundamental shift in how America thought about the economy and the role of government. Starting in the 1970s and exploding in the 1980s, a political philosophy called neoliberalism took control of both major parties.

Neoliberalism is based on one core belief: free markets work better than government at organizing society. The philosophy promotes four main policies:

- Deregulation - removing government rules seen as barriers to business

- Privatization - selling public services and assets to private companies

- Free trade - eliminating barriers to international commerce

- Minimal government - cutting public spending and letting markets solve problems

Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher became the faces of this movement. Reagan won the 1980 presidential election by promising to "get government off the backs" of Americans. He argued that regulations strangled innovation and that private enterprise, freed from government control, would create prosperity for everyone.

Reagan's War on Public Broadcasting

Reagan's neoliberal vision extended directly to media. He did not believe government had any role in shaping how information reached citizens. In his view, news was just another product that the market should control.

Reagan appointed Mark S. Fowler to chair the Federal Communications Commission in 1981. Fowler's philosophy was blunt and revolutionary. He famously said television was just "a toaster with pictures." This wasn't a joke. It was a declaration: broadcasting is not a public trust requiring special treatment. It is an appliance, a business, a commodity like any other.

The old FCC had believed airwaves were a scarce public resource. Because only a limited number of broadcast frequencies existed, the government licensed them with strings attached. Broadcasters had to serve "the public interest." They held a public trust.

Fowler rejected this entirely. He argued that with cable and satellite expanding, scarcity no longer existed. Viewers could change the channel if they wanted different perspectives. The market, through consumer choice, would naturally provide diversity. Government regulation was not just unnecessary but harmful. It created a "chilling effect" where stations avoided controversial topics to escape regulatory burdens.

The Fairness Doctrine Dies: August 1987

The Fairness Doctrine had required two things since 1949:

- Cover controversial issues of public importance

- Present contrasting viewpoints on those issues

It did not mandate equal time or force fake balance. It simply prevented broadcasters from presenting only one side of major public debates. If a station aired an editorial supporting a political candidate, it had to provide an opportunity for opposing views to be heard.

In August 1987, Reagan's FCC voted to eliminate the Fairness Doctrine. The reasoning was pure neoliberal ideology:

Old view: Airwaves are a public resource. Government must ensure citizens hear multiple perspectives to make informed decisions.

New view: Broadcasting is a business. The "marketplace of ideas" will naturally provide diversity. Government regulation interferes with free speech and free markets.

Congress actually passed legislation to make the Fairness Doctrine permanent law. Reagan vetoed it. The doctrine died.

Immediate Consequences: The Rise of Partisan Media

The effects were immediate and dramatic. In 1988, Rush Limbaugh launched his national talk radio show. It would not have been possible a year earlier. Under the Fairness Doctrine, stations airing three hours of conservative commentary daily would have faced regulatory pressure to provide contrasting viewpoints. The business model didn't work under those constraints.

With the doctrine gone, a new model exploded: the partisan echo chamber. Stations could dedicate entire broadcast days to a single political perspective. This was more profitable than balanced news. It built loyal audiences who tuned in not just for information but for validation and emotional reinforcement.

Fox News launched in 1996 with the slogan "Fair and Balanced" while operating as explicitly conservative counter-programming to what it called the "liberal mainstream media." MSNBC followed by positioning itself for liberal audiences. The market provided ideological choices, exactly as neoliberal theory predicted. But it did not provide shared truth. It provided competing realities sold to separate customer bases.

The Telecommunications Act of 1996: Consolidation

The Fairness Doctrine's repeal was just the beginning. The broader wave of media deregulation continued through the 1990s. The Telecommunications Act of 1996, signed by President Bill Clinton, represented the triumph of neoliberal media policy across both parties.

The Act lifted ownership caps that had limited how many media outlets one corporation could control. The stated goal was to increase competition by letting companies grow larger and invest more. The actual result was massive consolidation.

In 1983, 50 corporations controlled most American media. By 2000, that number had fallen to six. By 2020, five conglomerates controlled roughly 90% of what Americans read, watched, and heard. Local newspapers were bought by chains and stripped for profit. Local TV stations became outlets for standardized programming produced by distant corporate headquarters. Diverse editorial voices gave way to cost-cutting and profit maximization.

The neoliberal promise was that deregulation would create competition and diversity. The reality was concentration and homogenization. But not the homogenization of viewpoint. Instead, the homogenization of economic incentive: every outlet, regardless of political slant, optimized for engagement and profit rather than civic function.

Part III: The Destruction of Public Broadcasting

While commercial media consolidated, public media faced systematic defunding. This represents another dimension of neoliberal ideology in action: the belief that government should not be involved in providing information to citizens.

PBS and NPR: The Public Broadcasting Mission

The Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 created the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which funds PBS (Public Broadcasting Service) and NPR (National Public Radio). The goal was explicit: create media outlets insulated from both commercial pressures and direct political control. These institutions would serve the public interest rather than advertiser interest or partisan agendas.

PBS and NPR were never fully publicly funded like the BBC in Britain. They relied on a mix of government appropriations, corporate sponsorships, and individual donations. But federal funding was meant to provide a base that allowed editorial independence.

Decades of Cuts and Political Attacks

Neoliberal ideology has treated public broadcasting as suspect from the start. If markets efficiently provide everything society needs, why should taxpayers fund media? This skepticism has manifested in repeated funding cuts and political attacks.

Reagan tried to eliminate federal funding for public broadcasting entirely in the 1980s. He failed, but he succeeded in reducing it. Every subsequent Republican administration has proposed cuts. The Trump administration's 2018 budget called for eliminating all federal funding for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, arguing it was "no longer necessary" given the "proliferation of media sources."

These attacks have been partially bipartisan. Both parties have treated public broadcasting as a target when looking for budget savings. Federal appropriations for public media have declined dramatically when adjusted for inflation. In 1980, federal funding covered about 40% of public broadcasting budgets. By 2020, it was less than 15%.

The Consequences of Starving Public Media

Reduced federal funding has forced PBS and NPR to rely more heavily on corporate sponsorships and wealthy donors. This compromises the independence that public funding was meant to ensure. Stations must please underwriters. They must avoid offending potential donors. They must run fundraising drives that interrupt programming and favor wealthier, older audiences who can afford membership fees.

More broadly, the weakening of public broadcasting represents a philosophical surrender. It accepts the premise that information should be treated as a market commodity rather than a public good. It abandons the idea that democracy requires a media system designed to inform citizens rather than extract profit from them.

What Was Lost

The United States never built public media infrastructure on the scale of other democracies. Britain's BBC, Canada's CBC, Germany's ARD, Japan's NHK all receive substantial public funding and serve as cornerstones of their national information ecosystems. They have problems and critics, but they provide alternatives to purely commercial media logic.

America's weak public broadcasting system could have served a similar function. It could have provided a common ground, a shared source of information trusted across political lines. Instead, chronic underfunding and political attacks have marginalized it. PBS and NPR now serve primarily as niche products for educated, politically engaged audiences rather than as genuine public squares.

Part IV: The Digital Acceleration

If traditional media deregulation fractured the shared information space, social media atomized it into millions of personalized bubbles. Platforms like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and TikTok introduced a new dynamic: algorithmic curation at industrial scale.

These platforms do not simply transmit information. They actively shape what users see based on predictions about what will keep them engaged. Engineers design algorithms to maximize time spent on the platform, content shared, and emotional reactions triggered. These metrics determine what succeeds and what disappears.

Engagement Over Accuracy

The consequences have been severe. Social media platforms have become primary news sources for large portions of the American population. A 2021 Pew Research study found that roughly half of Americans get news from social media at least sometimes. For Americans under 30, the percentage is much higher.

Yet these platforms operate according to fundamentally different principles than journalism. Traditional news organizations, whatever their flaws, employed editors who made decisions about what to publish based on newsworthiness and verification. Social media algorithms make no such judgments. They optimize for engagement.

This creates systematic bias toward content that triggers strong emotions, confirms existing beliefs, or provokes outrage. Nuanced, balanced reporting performs poorly in this environment. Misinformation, conspiracy theories, and partisan propaganda often perform much better because they are designed to provoke the emotional reactions that algorithms reward.

Personalized Realities

Each social media user inhabits a partially unique information environment curated by algorithms they neither understand nor control. This creates what researchers call "filter bubbles." Users encounter primarily content that reinforces their existing views. Algorithms learn what keeps specific users engaged and serve more of it.

This personalization is far more extensive than old-fashioned media bias. A Fox News viewer and an MSNBC viewer got different perspectives, but they knew about the same events. Social media users can inhabit completely different information universes. Major news stories in one bubble may not appear at all in another. What seems like consensus in one community may be invisible to another.

Research consistently shows this effect. Social media users dramatically overestimate how many people agree with them. They underestimate the reasonableness of people with different views. This happens not because users are stupid or closed-minded, but because algorithmic curation systematically shields them from contrary perspectives.

The Democratization Trap

Social media has democratized information production in important ways. It has given voice to previously marginalized perspectives. It has enabled social movements and citizen journalism. These are real benefits.

But democratizing production without effective quality control has flooded the information ecosystem with content optimized for virality rather than accuracy. Anyone can publish. Anything can go viral. There is no systematic mechanism for distinguishing reliable information from propaganda, misinformation, or outright fabrication.

Traditional journalism had gatekeepers. Those gatekeepers had biases and often excluded important voices. But they also provided some baseline quality control. Social media has no effective gatekeepers at all. The algorithm is the gatekeeper, and it cares only about engagement.

Part V: The Breakdown of Democratic Citizenship

This transformation has corroded the foundations of democratic self-government in several ways.

The End of Shared Deliberation

Democracy requires citizens to engage with opposing arguments, consider alternative perspectives, and negotiate compromises based on common premises. When citizens inhabit separate information ecosystems with incompatible narratives about basic facts, this deliberative process becomes impossible.

Political conflict stops being about competing visions for shared problems. It becomes existential struggle between incompatible realities. Climate change is either a civilizational threat or a hoax. COVID-19 either killed a million Americans or was wildly exaggerated. Elections are either secure or stolen. There is no common ground from which to negotiate because there is no shared understanding of what is actually happening.

The Legitimacy Crisis

When election results, public health measures, or judicial decisions get reported through fundamentally different frames, or dismissed entirely as fraudulent, the losing side increasingly refuses to accept outcomes as legitimate. This is not mere partisan disappointment. It reflects a rational response to genuinely believing that the system has been corrupted or captured by malevolent forces.

The January 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol illustrates this dynamic. The attackers were not cynical opportunists. Many genuinely believed the election had been stolen because they inhabited information environments where that narrative was constantly reinforced. They consumed media that told them democracy was being stolen and they needed to stop it. This was not a failure of civic education in the traditional sense. It was a failure of the information system that fed them a completely false reality.

Weaponized Uncertainty

When mainstream media institutions lack cross-partisan trust, political actors can dismiss inconvenient facts simply by labeling them "fake news" or "mainstream media bias." This strategy does not require proving an alternative narrative true. It merely requires introducing sufficient doubt to paralyze decision-making or delegitimize institutions.

Donald Trump's presidency showcased this tactic systematically. Any negative news coverage could be dismissed as "fake news from the mainstream media." This worked not because Trump proved the coverage false, but because large portions of the Republican base already distrusted those outlets. The lack of shared epistemic authority meant there was no neutral arbiter who could referee factual disputes.

The result is what researchers call "reality apathy." Citizens learn they cannot determine what is true, so they retreat to tribal affiliation as their primary guide. They believe what their side says not because they have verified it, but because they trust their side more than the other. Politics becomes pure identity rather than reasoned deliberation.

The Local News Collapse

While national partisan media expanded, local news infrastructure collapsed. Between 2004 and 2024, more than 2,500 American newspapers closed. Many communities now have no local newspaper at all. These "news deserts" lack any systematic accountability journalism covering city councils, school boards, county commissioners, or local courts.

Local news historically served crucial democratic functions. It covered institutions too small to attract national attention but directly affecting citizens' lives. It provided information relevant across partisan lines because everyone cares about their local school's budget or whether the mayor is corrupt. It built community cohesion by giving people shared knowledge about their immediate environment.

The collapse happened because the economics no longer worked. Craigslist and other online platforms destroyed classified advertising, which had subsidized local reporting. National chains bought local papers, extracted profit, then abandoned them when returns declined. No alternative funding model emerged at scale.

The vacuum has been filled partly by national partisan media and partly by algorithmically-curated social feeds. Neither performs the democratic functions of local news. National media covers local stories only when they fit larger narratives. Social media provides no systematic coverage at all, just whatever happens to go viral.

Part VI: The Neoliberal Trap

All of these failures trace back to a core ideological error: treating information as just another market commodity. The neoliberal argument was that deregulation and market competition would provide diversity and quality. The market would give consumers what they wanted. Bad information would be driven out by good information. Consumer choice would ensure accountability.

This was always theoretically suspect. Information has unique characteristics that make it unsuitable for pure market provision:

Information is a public good. One person's consumption does not reduce availability to others. This creates free-rider problems that markets handle poorly.

Information has externalities. An informed citizenry benefits everyone, including those who did not pay for the information. Markets underprovide goods with positive externalities.

Information quality is difficult to assess. Consumers often cannot judge accuracy without expertise the information itself is supposed to provide. This creates market failure through information asymmetry.

Democratic information has non-market value. The information citizens need for self-governance may not be the information they want to pay for or consume voluntarily.

The empirical record has confirmed the theoretical concerns. Market-driven media has not provided diverse, high-quality information serving democratic needs. It has provided increasingly fragmented, partisan, engagement-optimized content serving advertiser needs and investor returns.

Part VII: Paths Forward

Fixing this crisis requires rejecting the premise that markets alone can provide the information infrastructure democracy requires. Several reforms are necessary:

Rebuild Public Media Infrastructure

The United States needs significant public investment in media institutions explicitly insulated from both commercial pressures and direct political control. This could follow several models:

Expanded public broadcasting with funding levels comparable to the BBC or CBC. Federal appropriations should cover the majority of operating costs, eliminating dependence on corporate underwriters or pledge drives. Editorial independence would be protected through governance structures that keep both political parties and donors at arm's length.

Civic journalism cooperatives owned by journalists and community members rather than profit-seeking investors. These would operate on nonprofit models with revenue from memberships, foundation grants, and civic-minded donors.

Public funding for local news through mechanisms like journalism tax credits, postal subsidies for news distribution, or direct grants to newsrooms serving communities lacking adequate coverage.

The goal is not state-controlled media. It is media structured to serve civic needs rather than maximize profit or partisan advantage.

Regulate Digital Platforms as Public Infrastructure

Social media platforms must be understood as critical infrastructure with profound effects on democratic function. Current law treats them as neutral technology companies with no responsibility for content. This is fiction. Their algorithms actively shape what information spreads and what disappears.

Reform options include:

Algorithmic transparency requirements forcing platforms to disclose how content is ranked and recommended. Independent researchers and regulators should be able to audit these systems.

Mandatory design changes reducing the amplification of misinformation and extreme content. Platforms could be required to slow the spread of novel claims, allow verification before viral distribution, or reduce emotional manipulation techniques.

Public interest algorithms developed by non-profit entities or required as alternative options. These would optimize for democratic values like exposure to diverse perspectives rather than engagement metrics.

Breaking up monopolies to reduce the concentration of power over information distribution. No single corporation should control the information environment for billions of people.

Invest in Media Literacy Education

Citizens need systematic education in evaluating sources, understanding media economics, recognizing manipulation techniques, and navigating complex information environments. This cannot be a one-time intervention but must be integrated throughout civic education.

Schools should teach:

- How to evaluate source credibility and bias

- How social media algorithms work and why they show specific content

- How to recognize common misinformation techniques

- The difference between news, opinion, and propaganda

- How media companies make money and how that affects content

This education must start young and continue throughout life. Adult education programs, public libraries, and community organizations all have roles to play.

Create Economic Models That Reward Accuracy

Journalism needs funding mechanisms that allow professional standards to operate rather than forcing optimization for engagement. Options include:

Nonprofit news organizations funded by foundations, membership fees, and civic-minded donors rather than advertisers or investors demanding returns.

Cooperative ownership where journalists and communities control outlets rather than distant shareholders or private equity firms.

Public subsidies tied to democratic accountability rather than profit. This could include tax credits for journalism jobs, reduced postal rates for news distribution, or direct grants to newsrooms meeting public-interest standards.

Philanthropy at scale with major funders supporting quality journalism as civic infrastructure rather than charitable extra.

The fundamental principle is that information necessary for democracy should not depend entirely on its profitability. Markets have a role, but they cannot be the only mechanism.

Conclusion: Rebuilding the Commons

The data tells a story of institutional failure. The near-disappearance of Republicans from mainstream journalism and the collapse of cross-partisan trust are symptoms of a deeper pathology. The transformation of information from public good to market commodity has shattered the epistemic commons democracy requires.

This was not accidental. It resulted from deliberate policy choices driven by neoliberal ideology. The repeal of the Fairness Doctrine, the deregulation of media ownership, the defunding of public broadcasting, and the failure to regulate digital platforms all reflect a consistent premise: that markets should control information and government should stay out.

That premise has failed empirically. The market has not provided the diverse, accurate information citizens need for self-governance. It has provided fragmented, partisan, engagement-optimized content that serves economic incentives rather than democratic needs.

Reversing this requires policy changes, certainly. But it requires something deeper: rejecting the notion that information is merely another commodity. Democracy cannot function when its members inhabit incompatible realities. Citizens cannot govern themselves when they cannot agree on basic facts.

Restoring American democracy requires reconstructing a shared epistemic commons. This does not mean enforced conformity or suppression of dissent. It means institutional structures that make truth-seeking economically viable and civically valued. It means treating information infrastructure as public goods requiring public investment and democratic accountability.

The alternative is continued fragmentation into mutually hostile tribes, unable to recognize each other's humanity or negotiate shared futures. This is not just a media crisis or a political crisis. It is a crisis of democratic capacity itself.

The path forward exists. Other democracies maintain stronger public media systems and more effective information regulation. The United States once had stronger civic information institutions and could build them again. What is required is not technical innovation but political will: the will to recognize that markets alone cannot sustain democracy, and that public investment in information infrastructure is not government overreach but democratic necessity.

The choice is clear. Continue treating information as a commodity and watch democracy dissolve into tribal conflict over incompatible realities. Or rebuild information as a commons and restore the shared ground citizens need to govern themselves. The data has already shown which path America has been on. The question is whether it will choose a different one.