Architecture of Success

Explore the core thesis of Why Nations Fail by Acemoglu and Robinson, emphasizing the critical role of inclusive versus extractive institutions in shaping national prosperity.

The Architecture of Success: How Nations Fail and Succeed Through Institutional Design

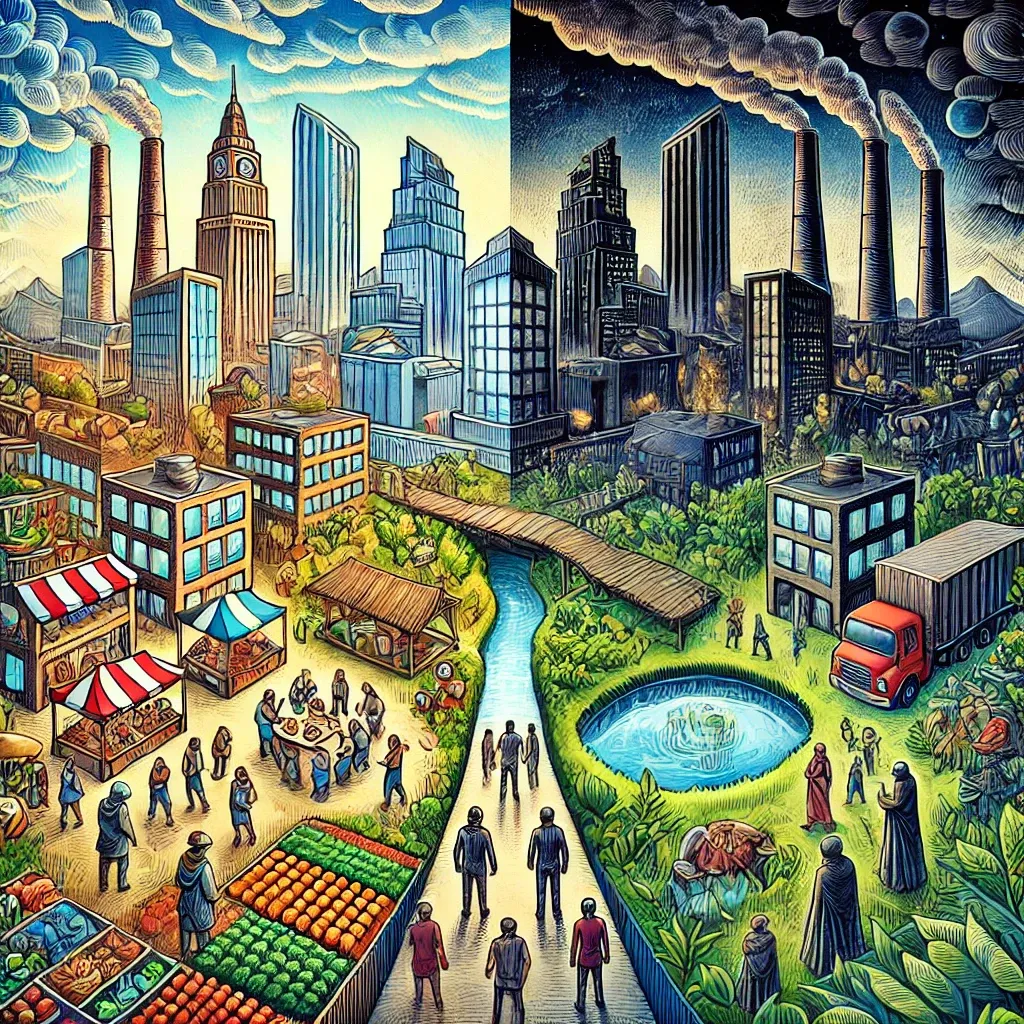

Picture a tale of two cities: one thrives with bustling markets and innovative enterprises, while the other stagnates under the weight of corruption and concentrated power. What separates them isn't resources, culture, or even initial wealth—it's the invisible architecture of their institutions. This fascinating intersection of historical wisdom and modern economic theory reveals a profound truth about why nations succeed or fail.

Let's visit this from the point of view of the "Why Nations Fail" by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson and using this quote as the standard; “Government is instituted for the common good; for the protection, safety, prosperity and happiness of the people; and not for the profit, honor, or private interest of any one man, family, or class of men.” - John Adams

Core principles

"Why Nations Fail" presents a compelling institutional theory of economic development. The core argument is that the success or failure of nations is primarily determined by their institutions, rather than factors like geography, culture, or natural resources. Here are the key principles:

- Institutional Differences: The authors argue that the key difference between prosperous and poor nations lies in their institutions - specifically whether they are "inclusive" or "extractive."

- Inclusive vs. Extractive Institutions:

- Inclusive political institutions distribute power broadly and constrain its abuse

- Inclusive economic institutions protect private property rights, create level playing fields, and encourage investments in new technologies

- Extractive institutions concentrate power among elites and are designed to transfer wealth and resources from the broader population to those elites

- Historical Path Dependence: The authors demonstrate how critical junctures in history (like colonization) set nations on different institutional paths that persist over time.

- Virtuous and Vicious Cycles: Inclusive institutions tend to reinforce each other, creating virtuous cycles of prosperity. Extractive institutions similarly create vicious cycles of poverty.

- Creative Destruction: Inclusive institutions allow for economic "creative destruction" - the process where new innovations replace old ones. Extractive institutions often resist this change to protect established interests.

Critical Junctures: Moments in history where the trajectory of institutions can dramatically shift, creating long-lasting effects through path dependence.

Example: The Black Death in Europe weakened feudal institutions, while in Eastern Europe it strengthened them, creating divergent development paths that lasted centuries

The DNA of Prosperous Nations

Think of institutions as the DNA of nations—they contain the code that determines how a society will develop and function. Acemoglu and Robinson's groundbreaking research in "Why Nations Fail" provides compelling evidence for this genetic metaphor, showing how institutional patterns replicate across generations.

Inclusive Institutions: Systems that distribute power broadly, protect individual rights, and create equal opportunities for economic participation. Like a healthy ecosystem, they maintain balance through diversity and interconnection.

Example: The dramatic divergence between North and South Korea—starting from identical cultural and geographical conditions, their radically different institutions led to vastly different outcomes

The opposite reveals a crucial contrast:

Extractive Institutions: Systems designed to concentrate benefits among a small elite while extracting resources from the broader population. Like a parasitic relationship, they eventually weaken their host system.

Example: Zimbabwe under Robert Mugabe, where initially promising institutions became increasingly extractive, leading to economic collapse

The Mechanics of Institutional Evolution

Acemoglu and Robinson identify several key mechanisms that determine institutional development:

1. The Iron Law of Oligarchy

Institutional Persistence: The tendency of extractive institutions to create powerful beneficiaries who resist reform, creating what economists call path dependence.

Historical Example: The persistence of extractive institutions in colonial Spanish America, despite independence, through what they term "institutional continuity"

2. The Virtuous Circle

Inclusive institutions create what game theorists call positive feedback loops:

- Economic inclusion leads to broader political participation

- Broader participation strengthens inclusive institutions

- Innovation and creative destruction become self-reinforcing

3. The Red Queen Effect

Institutional Arms Race: Named after the Red Queen in Alice in Wonderland, this describes how institutions must constantly evolve just to maintain their position—standing still means falling behind.

Modern Example: The constant adaptation of regulatory frameworks to keep pace with technological change

Critical Historical Divergences

Acemoglu and Robinson's work identifies several pivotal moments that demonstrate their theory:

- The Glorious Revolution in England (1688) This represented what they call a contingent path toward inclusive institutions:

- Limited monarchy created checks on power

- Property rights became more secure

- Financial markets developed

- The Industrial Revolution found fertile ground

- The Americas Divergence The contrast between North and South America provides what social scientists call a natural experiment:

- Different colonial institutions led to different development paths

- The United States and Canada developed inclusive institutions

- Much of Latin America maintained extractive colonial patterns

- The Industrial Revolution's Spread The response to industrialization created what economists call institutional bifurcation:

- Some nations embraced creative destruction

- Others tried to block change to protect elite interests

- The resulting divergence shaped modern global inequality

Modern Applications and Implications

The insights from "Why Nations Fail" yield several crucial lessons for contemporary development:

The Development Trap: The tendency of extractive institutions to create stable but inefficient equilibria that resist change.

Example: The persistence of poverty in resource-rich nations due to what economists call the "resource curse"

When John Adams declared that "Government is instituted for the common good," he wasn't merely making a moral proclamation—he was articulating what modern institutional economics would later prove empirically. Let's unpack this convergence of classical wisdom and contemporary understanding.

Breaking the Cycle

Successful institutional transformation requires what we might call synchronized change:

- Political and economic reforms must reinforce each other

- Broad coalitions must support change

- International context must be favorable

The Role of State Capacity

State Capacity: The ability of governments to effectively implement policies and provide public goods.

Critical Insight: Even well-designed inclusive institutions require state capacity to function effectively

The Universal Pattern Revisited

Acemoglu and Robinson's work reveals a profound truth: the success of nations depends on their ability to create what complex systems theorists call emergent order through inclusive institutions. This order emerges from:

- Broad-based political participation

- Economic opportunities for innovation

- Protection of property rights

- Constraints on power concentration

Looking Forward

The challenges of the 21st century—technological disruption, climate change, global inequality—make understanding institutional development more crucial than ever. The insights from "Why Nations Fail" suggest that success will come to societies that can:

- Maintain inclusive institutions while adapting to change

- Prevent the concentration of power in new domains (like digital platforms)

- Foster innovation while managing its disruptive effects

- Build state capacity while preventing state capture

In this light, Adams' wisdom about government for the common good becomes not just a moral imperative but a practical necessity for national success. The challenge is to apply these insights in an increasingly complex and interconnected world.

The Mechanics of Success

The brilliance of Adams' insight becomes apparent when we examine how successful institutions operate. They create what economists call positive feedback loops—virtuous cycles where good governance reinforces social trust, which in turn strengthens good governance.

Consider these interconnected elements:

- Protection and Safety When a society establishes reliable legal systems and property rights, it creates what game theorists call a cooperative equilibrium. People invest in the future because they trust the system to protect their interests.

- Economic Opportunity True prosperity emerges from what economist Joseph Schumpeter termed creative destruction—the process where new innovations replace old systems. This can only happen when institutions protect competition rather than privileged interests.

- Distributed Power Like a well-designed electrical grid, power in successful nations is distributed through multiple nodes and backup systems. This creates what political scientists call institutional redundancy—protection against single points of failure.

The Meta-Pattern: Coherence Through Competition

Here's where we discover a fascinating paradox: the most stable societies are those that institutionalize controlled instability. They create what evolutionary biologists call adaptive tension—just enough pressure to drive innovation without causing collapse.

Adaptive Tension: The optimal balance between stability and change that drives evolution in complex systems.

In practice: Democratic elections create regular peaceful transfers of power; market competition drives innovation without destroying social fabric

Practical Implications

This understanding yields profound insights for both developing and developed nations:

For developing nations, the path forward requires what we might call institutional bootstrapping—creating virtuous cycles that can overcome historical extractive patterns. This is challenging but not impossible, as demonstrated by nations like South Korea and Botswana.

For developed nations, the key challenge is institutional maintenance—preventing the natural tendency of successful systems to be captured by special interests. This requires constant vigilance and regular renewal of foundational principles.

The Universal Pattern

What emerges from this analysis is a universal pattern: successful nations create what systems theorists call emergent order—complex, adaptive systems that serve the common good not through central control but through well-designed rules of interaction.

Adams' wisdom and modern institutional economics converge on a profound truth: the success of nations isn't determined by resources or initial conditions, but by their ability to create and maintain institutions that harness human potential for the common good. This isn't just theory—it's a practical blueprint for national development that has been validated across centuries and continents.