Value of Money

Explore Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)—a framework that sees money as a state tool, not a market creation. Rooted in Chartalism, MMT explains currency value through taxes, debunks barter myths, and rethinks public spending in today’s fiat economies.

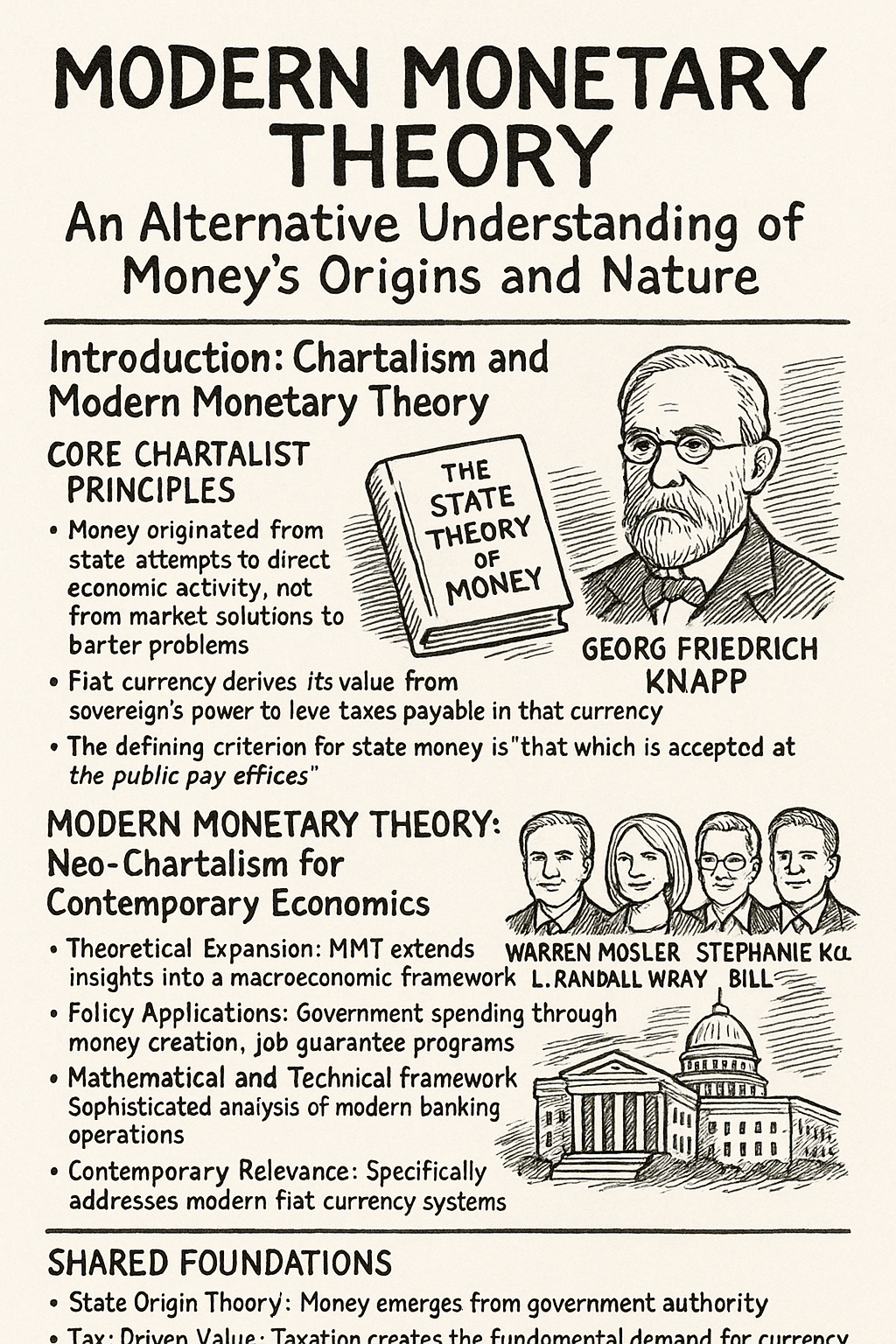

Modern Monetary Theory: An Alternative Understanding of Money's Origins and Nature

Introduction: Chartalism and Modern Monetary Theory

The ideas presented in this analysis represent the contemporary development of a monetary theory known as Chartalism, which has evolved into what is now called Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). Understanding the relationship between these concepts is crucial for grasping the full significance of this alternative approach to money.

Chartalism: The Original Foundation

Chartalism was developed by German economist Georg Friedrich Knapp in his 1905 work "The State Theory of Money" (translated into English in 1924). The term derives from the Latin word "charta," meaning token or ticket. Knapp argued that "money is a creature of law" rather than a commodity, directly challenging the prevailing "metallism" of his era, which tied money's value to precious metals like gold.

Core Chartalist Principles:

- Money originated from state attempts to direct economic activity, not from market solutions to barter problems

- Fiat currency derives its value from the sovereign's power to levy taxes payable in that currency

- The defining criterion for state money is "that which is accepted at the public pay offices"

- Money's acceptance stems from government authority rather than intrinsic value or market convenience

Modern Monetary Theory: Neo-Chartalism for Contemporary Economics

Modern Monetary Theory represents the revival and significant expansion of chartalist ideas for modern economic conditions. Economists Warren Mosler, L. Randall Wray, Stephanie Kelton, and Bill Mitchell are largely responsible for this revival, with Wray referring to it as "Neo-Chartalism" and Mitchell coining the term "Modern Monetary Theory" to describe this updated framework.

Key Evolutionary Developments from Chartalism to MMT:

Theoretical Expansion: While Chartalism focused primarily on explaining money's nature and origins, MMT extends these insights into a comprehensive macroeconomic framework that addresses banking systems, fiscal policy, employment, and inflation in modern fiat currency economies.

Policy Applications: Classical Chartalism was largely descriptive, but MMT provides detailed policy prescriptions including government spending through money creation, job guarantee programs, and deficit spending recommendations based on the understanding that sovereign governments with fiat currencies cannot become insolvent.

Mathematical and Technical Framework: MMT incorporates sophisticated analysis of modern banking operations, sectoral balance approaches, and detailed technical understanding of how money creation works in contemporary economies, building on but going far beyond Knapp's original theoretical foundation.

Contemporary Relevance: While Chartalism emerged as an alternative to gold standard thinking, MMT specifically addresses the realities of modern fiat currency systems and provides tools for understanding economic management in the post-Bretton Woods era.

Shared Foundations

Both Chartalism and MMT share fundamental principles that distinguish them from orthodox economic theory:

- State Origin Theory: Money emerges from government authority rather than market evolution

- Tax-Driven Value: Taxation creates the fundamental demand for currency that gives it value

- Rejection of Barter Mythology: Both theories reject the standard narrative of money evolving from barter systems

- Endogenous Money: Both view money as created within the economy through government and banking operations, rather than being externally determined

The analysis that follows represents this MMT perspective, incorporating both the foundational chartalist insights about money's true nature and the modern policy implications that flow from understanding how contemporary monetary systems actually operate.

The Orthodox Story of Money's Origin

The conventional narrative taught in schools and economics courses presents a linear evolution of money that begins with primitive barter systems. This story typically unfolds as follows:

The Barter Problem: The tale starts with Robinson Crusoe meeting Friday on a deserted island. Crusoe knows how to grow grain while Friday knows how to fish. They attempt to barter these goods directly, but this system proves inconvenient because it requires a "double coincidence of wants" - meaning that when Friday wants to trade fish, Crusoe must simultaneously want fish and be willing to trade grain for it on that exact day.

Evolution to Money: To solve this inefficiency, people supposedly searched for items that could serve as a medium of exchange. They might have started with seashells but eventually settled on gold through an evolutionary process. Gold became preferred because it possessed desirable characteristics: it was valuable, didn't deteriorate over time, and was portable.

The Goldsmith System: However, gold presented a security problem - people worried about theft. This led to the practice of storing gold with goldsmiths, who already had safes and security measures for their jewelry-making operations. Goldsmiths would issue receipts for deposited gold, and people discovered they could use these receipts for transactions instead of the actual gold, since recipients knew they could redeem the receipts for gold whenever needed.

Banking Development: Goldsmiths realized they didn't need to keep all deposited gold in their vaults since not all receipts would be redeemed simultaneously. This insight led to what economists call the "deposit expansion process" - issuing many receipts while keeping only a small fraction (perhaps 10%) of the actual gold for redemption on demand. These goldsmiths essentially became the first banks.

Orthodox View of Money's Nature: In this traditional framework, money exists primarily to "lubricate the market" and make transactions more efficient than barter. Specific money-denominated assets fulfill the medium of exchange function, and while the particular items serving as money have changed over time (from gold to modern currencies), the focus remains on money's role as a medium of exchange. Other functions of money are considered derivative of this primary medium of exchange function.

Fundamental Problems with the Orthodox Story

Lack of Historical Evidence for Barter Economies

The first major flaw in the orthodox narrative is the complete absence of archaeological or historical evidence for economies based on barter systems. David Graeber's influential book "Debt: The First 5,000 Years" (described as a runaway bestseller despite being approximately 5,000 pages long) demonstrates that anthropologists and historians have never discovered any economies anywhere in the world, no matter how far back in history they look, that were actually based on barter systems.

Money Predates Markets

Contrary to the orthodox story, historical evidence shows that money was not invented as a transaction-cost-minimizing device for already existing markets. Instead, money pre-exists markets. This relationship is the opposite of what the traditional narrative suggests.

Money is as Old as Writing

The earliest written records that archaeologists have discovered are all about money and monetary accounts. This reveals that writing itself was not invented by poets or storytellers, but by accountants who needed to keep track of money values and financial obligations. This historical fact demonstrates that money existed before markets developed, contradicting the fundamental premise of the orthodox story.

Complexity Problems with Market Selection

Even Austrian economists, who have long promoted the barter-to-money evolution story, now acknowledge significant problems with their theory. They admit that once you have more than about ten people and ten different commodities, it becomes extremely difficult for market processes of "higgling and haggling" to naturally settle on a single commodity to serve as money. Unless modern computing power is available to process the complex calculations involved, markets cannot efficiently select a single commodity to serve as universal money when dealing with many commodities and many participants.

Authority Involvement from the Beginning

Historical evidence demonstrates that authorities were always involved in monetary systems from their very inception. The creation of money and units of account always involved governmental or religious authorities - it was never a spontaneous market development between individuals like Robinson Crusoe and Friday.

Modern Money Lacks Intrinsic Value

The orthodox story struggles to explain why modern money has no intrinsic value, despite the entire narrative being built around the selection of valuable commodities (like gold) to serve as money. Today's currencies are not backed by or attached to any commodities and possess no intrinsic value. Furthermore, even ancient money, contrary to the goldsmith story, typically lacked intrinsic value as far back as historical records extend.

The Trust Problem and Infinite Regress

When confronted with the intrinsic value problem, orthodox economists often retreat to explanations based on "trust." They argue that people use money because they trust others will accept it - for example, trusting that they can use money at grocery stores or that "Billy Bob" will accept it in payment. However, this creates an infinite regress problem: if money's value depends on trust that others will accept it, what gives those others confidence to accept it? This circular reasoning provides what the some considers "a very thin argument to base the most important institution we have in modern economies" upon.

No Explanation for Money's Origin in the Economy

The orthodox circular flow models of economics cannot explain how money initially enters the economy. There's no clear mechanism described for how money gets into circulation in the first place.

An Alternative Theory: Money's Actual Origins

The Wergild Connection

Since money predates writing, and the first written records already discuss money, we cannot know with certainty how money originated - no one wrote a memo saying "today I invented money." However, the most convincing speculation comes from Philip Grierson, described as "the most famous coin collector in the world," who studied coins extensively at the University of Cambridge in England before donating his valuable collection to the university upon his death.

Grierson theorized that money originated from an ancient tribal practice called "wergild" (meaning "man price" in Germanic). This system was documented by Romans studying German tribal society, though anthropologists find similar practices in virtually every tribal society they encounter.

The Wergild System Explained

Under the wergild system, when someone caused injury to another person - including killing them - a fine was imposed that had to be paid to the victim's family. These fines were paid "in kind," meaning with actual goods like goats, cows, horses, sheep, or chickens. The type and quantity of payment depended on the severity of the injury caused.

The purpose of this system was to prevent blood feuds - the cycle of retributive violence that would otherwise occur (like the famous Hatfield and McCoy feud). Instead of allowing endless cycles of revenge killings, the wergild system provided a way to settle disputes through compensation.

The Intellectual Leap to Money

Grierson's theory suggests that the concept of systematically valuing things emerged from the wergild tradition. This represented a massive intellectual breakthrough because wergild involved comparing the relative values of different items - for instance, determining that one cow was equivalent to one hundred chickens in terms of compensation value.

This was a much bigger conceptual leap than previous measurement systems, which typically dealt with physical properties like length (measured by feet - literally the king's foot - or cubits). The idea of creating abstract units of value that could compare completely different objects was revolutionary.

Connection to Grain Weights

A significant clue supporting this theory is that every ancient money unit was originally the name of a grain weight unit. Examples include the shekel, lira, and pound - all were originally units for measuring grain weight. This suggests that someone had the innovative idea to use grain measurement systems as a way to measure the value of everything, not just grain itself.

Babylonian Implementation

By Babylonian times, this system was fully developed. Price lists showing the equivalents to the "mina" (a grain weight unit) were posted at temples. These temple authorities set the values of all goods and services in the economy. This system allowed people to know the standardized value of everything, as determined by religious and governmental authorities.

The Alternative View: What Money Actually Is

Money as State Monopoly and Social Measurement

Rather than being a market-created medium of exchange, money is fundamentally a state monopoly and a social unit of measurement. In America, for example, when people are asked about the value of any object, they respond in terms of dollars, not in terms of chickens or other commodities. As capitalism develops, an increasingly greater range of things can be measured and valued in terms of money.

State Money of Account

Almost without exception, the money unit of account used in any country comes from the state. Every time a new country is formed, it chooses its own money of account. The United States chose the dollar specifically because Americans didn't want to continue using the British pound after the Revolutionary War. The new nation modeled its currency after Spanish currency as a way to "thumb our nose at England" and assert independence.

Hierarchy of IOUs

The monetary system consists of a hierarchy of IOUs (I Owe You instruments), all denominated in the state's money of account. This includes:

- Bank money

- Government currency

- Private IOUs and debts

In America, all of these are denominated in US dollars. The specific form these instruments take depends on available technology - whether paper money, coins, or electronic money. These are all just different technological ways of recording "tally sticks" or keeping track of debts and credits.

Power-Based Value, Not Intrinsic Value

The value of currency is based on the power of the issuing authority, not on any intrinsic value of the currency itself. Currency doesn't need to have intrinsic value because its acceptance and value derive from the authority backing it.

Currency as Debt Records

Currency itself represents a record of debts, whether printed on paper or stamped on coins. It constitutes a promise to redeem, though the nature of what "redemption" means requires further explanation in the modern context.

Historical State Role

The state has played the central role in money's evolution from the very beginning, contrary to market-origin theories. This has been consistent throughout history and across different civilizations.

One State, One Currency Rule

Looking around the world today and back through approximately 5,000-6,000 years of history, we find what can be called the "one state, one currency rule." Each nation or state has its own currency. When the Soviet Union collapsed, every former member republic chose its own currency rather than continuing to share a common one.

Historically, exceptions to this rule were extremely small and virtually irrelevant. For example, Vatican State used the Italian lira, but this was a minor exception. The only major exception to this historical pattern is the Eurozone, which the some describe as "an experiment in an exception" that "has been disastrous."

Connection to Sovereignty

The one-state-one-currency pattern is not coincidental but is fundamentally tied to sovereign power, political independence, and fiscal authority. This explains why every new nation adopts its own currency as part of establishing its sovereignty.

Taxes Drive Money

The final and crucial element of this alternative theory is that taxes drive money and give it value. It is the power to impose taxes that represents the important sovereign power ensuring that currency has value. People must obtain and use the government's currency because they need it to pay their tax obligations to that government.

This tax-driven demand creates the fundamental value and necessity for currency, making it much more than just a convenient medium of exchange. Instead, it becomes an essential tool of state power and social organization, with its value ultimately derived from the government's ability to require its use for settling tax obligations.

Implications for Understanding Modern Economics

This alternative understanding of money's nature and origins has profound implications for how we think about modern economic policy, the role of government in the economy, and the relationship between fiscal and monetary policy. Rather than money being a neutral tool that emerged from market needs, it is revealed as a fundamental expression of state power and social relationships, with its value and function intimately connected to governmental authority and the taxation system.

The recognition that money predates markets, originates from state authority, and derives its value from tax obligations challenges many conventional economic assumptions and suggests the need for significantly different approaches to economic policy and understanding.