Systemic Analysis of American Democratic Decay and Need for Constitutional Renewal

USA democratic decay? Analyze systemic issues & constitutional renewal. #AmericanDemocracy

The Moral Algorithm and the Architecture of Justice

Abstract

This thesis argues that American democracy has systematically deviated from its foundational moral framework—what John Adams articulated as government serving "the common good" rather than "private interest"—creating a cascading crisis of legitimacy, inequality, and civic breakdown. Through an interdisciplinary analysis integrating historical sociology, political economy, and constitutional theory, this work demonstrates how the transformation of democratic governance into market-driven systems has inverted the relationship between public service and private gain, producing measurable deterioration across economic, political, and social domains. The thesis proposes that restoration requires not incremental reform but structural realignment through constitutional amendment that severs the money-power nexus enabling systematic capture of democratic institutions.

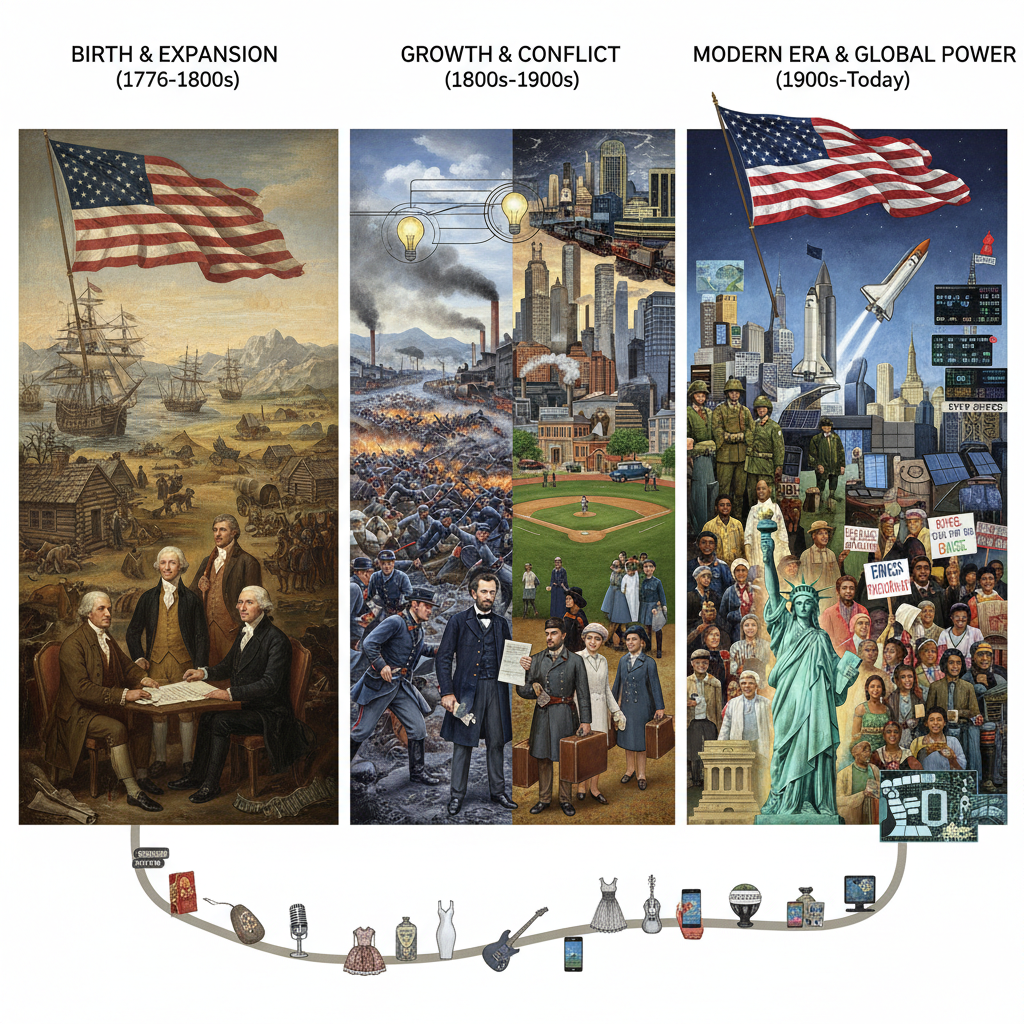

Introduction: The Equality Imperative and the Progress Paradigm

Human beings enter existence in a state of radical inequality—born into circumstances they neither chose nor control, yet which fundamentally shape their life trajectories, opportunities, and capacity to contribute to collective human advancement. This foundational reality creates what we might call the equality imperative: the moral and practical necessity for just societies to construct systems that level the playing field, not by guaranteeing identical outcomes, but by ensuring that accidents of birth do not predetermine life possibilities.

The American experiment was conceived as a systematic response to this challenge. The Founding Fathers, emerging from a colonial experience defined by corporate monopoly and aristocratic privilege, articulated what John Adams said and I call the "Moral Algorithm", a governing principle that subordinates private interest to public good. This algorithm, embedded in founding documents and revolutionary rhetoric, represents more than political philosophy; it constitutes a theory of human progress itself.

Progress, properly understood, is not technological advancement or economic growth in isolation, but the deliberate, generational expansion of human capability and problem-solving capacity. It occurs when societies successfully channel individual potential toward collective advancement, creating conditions where each person can contribute meaningfully to humanity's ongoing development. Conversely, vices—understood systemically rather than morally—are structural patterns that concentrate opportunity, exploit future potential, or suppress human development. The role of government, therefore, is not to judge these patterns but to optimize them: constraining systemic vices while amplifying conditions that unlock human potential.

This framework reveals that contemporary American dysfunction stems not from policy disagreements or partisan conflict, but from a fundamental inversion of the "Moral Algorithm". Where the Founding generation designed government to constrain private power for public benefit, the current system has been restructured to deploy public power for private benefit, a transformation that explains the cascading failures across American society.

Chapter 1: Historical Foundations and the Original Moral Algorithm

The Colonial Laboratory of Corporate Power

The American Revolution was fundamentally an anti-corporate revolution, though this dimension has been obscured in popular historical memory. The Boston Tea Party of 1773 represented not merely resistance to taxation, but organized opposition to what contemporary observers understood as corporate capture of government authority. The East India Company, granted monopolistic privileges by the Crown, exemplified how private interests could co-opt public power to extract wealth from productive communities.

The colonists' experience with the East India Company provided a laboratory for understanding how concentrated corporate power undermines democratic governance. The Company's tea monopoly was maintained not through market competition but through government-granted privileges that prevented colonial merchants from competing on equal terms. This arrangement enriched Company shareholders and Crown officials while impoverishing American communities—a pattern the Founders recognized as antithetical to just governance.

Thomas Paine captured this insight in Common Sense, distinguishing between society and government: "Society is produced by our wants, and government by our wickedness." Society emerges naturally from human cooperation and mutual aid, while government becomes necessary only to restrain those who would exploit cooperative systems for private gain. This analysis positioned American independence not as rejection of governance per se, but as an attempt to create governance systems that served social cooperation rather than private extraction.

Constitutional Architecture and the Common Good Framework

The moral algorithm articulated by John Adams, "Government is instituted for the common good; for the protection, safety, prosperity and happiness of the people; and not for the profit, honor, or private interest of any one man, family, or class of men", represented the constitutional embodiment of lessons learned from colonial experience. This principle established three foundational commitments:

Public Purpose Supremacy: Government authority derives from and must serve collective wellbeing rather than private accumulation. This principle directly contradicted European models where state power served monarchical or aristocratic interests.

Anti-Capture Mechanisms: The explicit rejection of governance "for the profit...of any one man, family, or class" constituted an early theory of regulatory capture, recognizing that concentrated interests would systematically attempt to co-opt public authority.

Adaptive Capacity: Adams's stipulation that government should be reformed "when their protection, safety, prosperity and happiness require it" embedded evolutionary mechanisms into constitutional theory, anticipating that power structures would require periodic realignment to maintain their public purpose.

The Founding generation understood that this moral algorithm required more than philosophical commitment; it demanded institutional architecture designed to prevent concentrated interests from capturing democratic processes. The separation of powers, federalism, and other constitutional mechanisms were intended not merely to prevent tyranny, but to ensure that government remained oriented toward public rather than private purposes.

Early Constraints on Corporate Power

The Founders' wariness of corporate power translated into concrete institutional limitations. Early American corporations were chartered for specific public purposes—building roads, establishing schools, providing municipal services—with strict temporal and geographic limitations. Corporate charters included explicit public benefit requirements and could be revoked for failing to serve community interests.

This approach reflected sophisticated understanding of what we now recognize as the principal-agent problem: how to ensure that entities granted public privileges (corporations) remain accountable to public purposes rather than redirecting those privileges toward private gain. The solution was institutional: tight democratic control over corporate charters, limited scope and duration of corporate privileges, and clear accountability mechanisms.

The contrast with contemporary corporate law is stark. Modern corporations operate under general incorporation statutes that grant broad powers with minimal public oversight, indefinite duration, and legal frameworks that prioritize shareholder wealth over public benefit. This transformation—from corporations as public servants to corporations as private wealth machines—represents a fundamental departure from founding principles.

Chapter 2: The Systematic Inversion—From Public Service to Private Extraction

The Rise of Neoliberal Governance

The transformation of American governance from public service to private extraction did not occur suddenly but through incremental changes that cumulatively inverted the constitutional order. This process, which we can label systematic inversion, represents the conversion of democratic institutions into mechanisms for concentrating wealth and power rather than distributing opportunity and capability.

The Powell Memorandum of 1971 provides crucial documentation of how this inversion was planned and implemented. Lewis Powell's strategic memo to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce outlined a comprehensive campaign to reassert corporate control over American institutions—universities, media, courts, and legislatures. Powell's analysis revealed sophisticated understanding of how ideological change precedes institutional capture: by reshaping how Americans think about the relationship between business and society, corporate interests could legitimize the reconstruction of government around private rather than public purposes.

The Powell strategy succeeded by reframing public institutions as inefficient impediments to economic growth rather than essential infrastructure for collective flourishing. This reframing enabled what political scientists call venue shopping: when democratic institutions resisted corporate priorities, those priorities were pursued through less democratic venues, regulatory agencies, courts, international trade agreements, where corporate influence faced fewer constraints.

The Money-Speech Equation and Democratic Capture

The Supreme Court's equation of money with speech, culminating in Citizens United v. FEC (2010), represents the legal codification of systematic inversion. By treating financial expenditures as protected speech, the Court created a constitutional framework where those with greater wealth enjoy greater political voice, directly contradicting democratic principles of equal citizenship.

This transformation enables what economists call the Cantillon Effect in political systems: those closest to the source of new money (or in this case, political influence) benefit first and most substantially from system changes. Wealthy interests can shape legislation, regulation, and judicial interpretation in ways that create more opportunities for wealth extraction, generating a self-reinforcing cycle of capture and concentration.

The practical mechanics of this system are visible in contemporary legislative processes. Corporate lobbyists often draft legislation that is introduced with minimal modification by elected officials. Regulatory agencies operate through "revolving door" arrangements where officials move seamlessly between government positions and private sector roles in the industries they previously regulated. These arrangements create systematic incentives for public officials to prioritize private interests that offer future employment opportunities.

Policy Consequences: The Privatization of Public Function

Systematic inversion manifests through comprehensive privatization of functions that democratic theory assigns to public authority. This privatization operates not only through direct sale of public assets but through more subtle mechanisms that redirect public resources toward private accumulation:

Financial Privatization: Tax policy increasingly favors capital income over labor income, while public debt instruments provide guaranteed returns to private investors rather than funding public investment. The result is that government debt service increasingly transfers public resources to private wealth holders.

Infrastructure Privatization: Public-private partnerships for roads, schools, prisons, and utilities typically involve public financing with private profit extraction, socializing costs while privatizing returns. These arrangements often cost more than direct public provision while reducing democratic accountability.

Social Service Privatization: Healthcare, education, and social welfare increasingly operate through private entities that extract profit from public funding. Charter schools, private prisons, and managed care organizations exemplify how public purposes become vehicles for private accumulation.

Regulatory Privatization: Industry self-regulation and capture of regulatory agencies enables private interests to write the rules governing their own behavior, eliminating meaningful constraints on rent-seeking behavior.

Each form of privatization follows similar logic: public authority and resources are redirected to generate private returns while costs and risks remain socialized. This pattern directly reverses the moral algorithm by using government power to serve private rather than public interests.

Chapter 3: Systemic Consequences and the Crisis of Legitimacy

Economic Symptoms: Wealth Concentration and Opportunity Hoarding

The systematic inversion of American governance has produced measurable economic consequences that validate theoretical predictions about capture dynamics. Wealth concentration has reached levels not seen since the 1920s, with the top 1% controlling more wealth than the entire middle class. This concentration reflects not market efficiency but successful rent-seeking: the use of political power to extract wealth without creating corresponding value.

Opportunity hoarding represents perhaps the most damaging consequence of systematic inversion. Educational credentialism, occupational licensing, zoning restrictions, and financial barriers systematically exclude capable individuals from economic participation, reducing overall productivity while protecting established interests. These barriers particularly affect young people, minorities, and working-class families, creating what economist Raj Chetty calls the "fading American Dream"—declining rates of upward mobility that contradict core American promises.

The collapse of small business formation illustrates how systematic inversion undermines entrepreneurial capitalism itself. Corporate consolidation, regulatory complexity favoring large firms, and financial system bias toward established players create barriers to new business formation. The result is reduced competition, innovation, and economic dynamism—outcomes that harm consumers and workers while protecting established corporate interests.

Political Symptoms: Democratic Deficit and Legitimacy Crisis

The conversion of democratic institutions into wealth concentration mechanisms has produced a democratic deficit: government responsiveness to public preferences has declined measurably while responsiveness to elite preferences has increased. Political scientists Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page demonstrated empirically that public opinion has negligible influence on policy outcomes when it conflicts with elite preferences, while elite preferences are implemented regardless of public opinion.

This democratic deficit manifests through several mechanisms:

Agenda Control: Wealthy interests shape which issues receive political attention and how those issues are framed. Climate change, inequality, and corporate power—issues where public opinion often conflicts with elite interests—receive less political attention than their objective importance warrants.

Policy Complexity: Legislation increasingly takes forms that obscure redistributive consequences, making democratic accountability difficult. Tax expenditures, regulatory exemptions, and complex subsidy programs transfer wealth upward while appearing technically neutral.

Institutional Capture: Regulatory agencies, courts, and even Congress operate with decision-making processes that systematically favor organized interests over diffuse public interests. The complexity of modern governance creates multiple veto points that well-resourced interests can exploit.

The result is what political scientist Steven Levitsky calls competitive authoritarianism: formal democratic institutions persist while actual democratic control erodes. Elections continue, but electoral outcomes have diminishing influence over policy directions, particularly on issues affecting wealth distribution and corporate power.

Social Symptoms: Atomization and Civic Breakdown

Systematic inversion has degraded the social infrastructure necessary for democratic citizenship. Social atomization—the breakdown of associations, communities, and collective institutions—reflects not cultural change but structural transformation. When public institutions are defunded and privatized, citizens lose venues for collective action and shared identity formation.

The decline of labor unions exemplifies this dynamic. Union membership has collapsed not primarily due to worker preferences but due to systematic legal and regulatory changes that favor employers while constraining worker organization. This decline has eliminated one of the primary institutions through which working people participated in democratic governance, contributing to political disengagement and resentment.

Civic knowledge has deteriorated as educational institutions increasingly emphasize individual economic advancement over collective citizenship. Civics education has been defunded while business-oriented curricula expand, producing citizens who understand themselves primarily as consumers and employees rather than as participants in democratic self-governance.

The mental health crisis, rising suicide rates, and social isolation reflect not individual pathology but social structure breakdown. When people cannot afford housing, healthcare, education, or economic security despite full-time employment, the social contract loses credibility. The resulting anxiety, depression, and despair represent rational responses to systematically irrational arrangements.

Chapter 4: Alternative Frameworks and Constitutional Solutions

Beyond Rights Absolutism: Toward Democratic Constitutionalism

The crisis of American democracy cannot be resolved through conventional political reform because the crisis stems from constitutional-level transformation. Addressing systematic inversion requires constitutional solutions that restore the moral algorithm through institutional design rather than depending on political actors to voluntarily constrain their own power.

The current approach to constitutional interpretation—what legal scholar Mark Tushnet calls rights absolutism—frames governance questions as conflicts between abstract individual rights rather than as design problems for democratic institutions. This framework obscures how institutional arrangements shape the distribution of power and opportunity, focusing attention on judicial interpretation rather than democratic participation.

Democratic constitutionalism offers an alternative framework that emphasizes constitutional design for effective democratic governance. Rather than treating the Constitution as a fixed document interpreted by judicial experts, this approach treats constitutional questions as ongoing challenges in institutional design that require democratic participation to resolve.

Applied to systematic inversion, democratic constitutionalism suggests that constitutional amendments should focus on structural relationships rather than individual rights. The goal is not to grant new rights but to restore institutional arrangements that enable democratic governance to constrain private power accumulation.

The Amendment Strategy: Severing Money from Political Power

The most direct solution to systematic inversion is constitutional amendment that severs the connection between private wealth and political power. This approach targets the root mechanism enabling capture while providing immediate enforcement through existing judicial frameworks.

A comprehensive amendment would establish four principles:

Money Is Not Speech: Overturning the Supreme Court's equation of financial expenditures with protected speech, enabling democratic regulation of political spending without First Amendment conflicts.

Corporations Are Not People: Clarifying that constitutional rights apply to human beings rather than artificial entities, preventing corporate constitutional claims that undermine democratic regulation.

Public Election Funding: Mandating public funding for all federal elections while prohibiting private contributions, ensuring that electoral success depends on public rather than private support.

Revolving Door Prohibition: Barring elected officials and regulatory personnel from private sector employment in industries they oversaw, eliminating incentives for regulatory capture.

This amendment strategy is powerful because it addresses systematic inversion at its source while enabling broader reforms through restored democratic processes. Once private money is removed from politics, democratic institutions can address other aspects of systematic inversion—tax policy, regulatory capture, privatization—through normal legislative processes.

Implementation Through Democratic Mobilization

Constitutional amendment requires extraordinary political mobilization that conventional interest group politics cannot achieve. However, the amendment strategy offers unique advantages for building broad coalitions:

Clarity of Purpose: Unlike complex policy proposals, constitutional amendment provides clear, understandable goals that can unite diverse constituencies around shared democratic values rather than specific policy preferences.

Non-Partisan Appeal: Both conservative and progressive voters support reducing corporate influence in politics, providing foundation for cross-party coalitions that transcend typical political divisions.

State-Level Momentum: Article V amendment procedures enable state-level organizing that can pressure federal action, following successful models like marriage equality campaigns.

Immediate Enforceability: Constitutional amendment creates immediate legal framework for enforcement rather than depending on future political cooperation.

The implementation path involves three phases: education about systematic inversion and constitutional solutions, organization of state-level campaigns for constitutional convention or legislative action, and enforcement through judicial and legislative mechanisms once amendment is ratified.

Chapter 5: Toward Regenerative Democracy

Beyond Neoliberalism: The Economics of Public Purpose

Implementing constitutional solutions to systematic inversion requires economic frameworks that support public purpose rather than private accumulation. Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) provides crucial insights for understanding how restored democratic governance could operate economically.

MMT's central insight—that monetarily sovereign governments are not revenue-constrained but resource-constrained—fundamentally reframes debates about public investment and social policy. Government's fiscal capacity is limited not by tax revenue but by real economic capacity: available labor, materials, technology, and productive capability.

This understanding enables what economist Stephanie Kelton calls purposeful spending: using fiscal policy to achieve full employment, environmental sustainability, and social equity rather than arbitrary budget balance. When government spending is guided by public purpose rather than private accumulation, it can address systematic underinvestment in education, infrastructure, healthcare, and environmental protection.

The Job Guarantee exemplifies how MMT principles could support democratic renewal. By offering employment at living wages to anyone willing to work on socially useful projects, government could provide economic security while addressing unmet public needs. This approach would reduce private sector labor market power while creating economic independence that enables democratic participation.

Regenerative Institutions and Civic Infrastructure

Restored democratic governance requires rebuilding the civic infrastructure that systematic inversion has degraded. Regenerative institutions are designed not merely to provide services but to strengthen democratic capacity through their operation.

Participatory Budgeting enables communities to directly allocate public resources, providing civic education while ensuring that spending reflects local priorities rather than elite preferences. Cities implementing participatory budgeting report increased civic engagement, improved government responsiveness, and stronger community solidarity.

Citizens' Assemblies offer mechanisms for addressing complex policy questions through deliberative democracy rather than special interest politics. Random selection ensures representation while extended deliberation enables informed decision-making that transcends initial prejudices and partisan positions.

Cooperative Enterprise provides economic models that embed democratic values in workplace organization. Worker cooperatives, platform cooperatives, and community land trusts demonstrate how economic activity can strengthen rather than undermine democratic citizenship.

Public Banking enables communities to keep locally-generated wealth within local economies rather than extracting it to distant financial centers. Public banks can provide patient capital for local development while generating revenue for public services.

These institutions are regenerative because they strengthen democratic capacity through their operation rather than simply delivering services efficiently. They provide venues for civic learning, collective action, and shared identity formation that enable ongoing democratic participation.

Global Implications and Democratic Internationalism

American democratic renewal has implications beyond national borders because systematic inversion is not uniquely American. Corporate capture of democratic institutions operates globally through trade agreements, tax havens, and international financial arrangements that constrain democratic sovereignty.

Democratic internationalism offers an alternative to both nationalist isolation and neoliberal globalization. This approach seeks international cooperation that strengthens rather than undermines domestic democratic capacity, supporting global standards for corporate accountability, tax cooperation, and environmental protection.

The Global Tax Justice movement demonstrates how international cooperation can constrain tax avoidance and wealth extraction that undermine democratic governance. By coordinating to eliminate tax havens and implement global minimum tax rates, nations can restore fiscal capacity for public investment while reducing incentives for capital flight.

Climate cooperation provides another venue for democratic internationalism, as climate change requires coordinated action that only democratic governance can legitimately provide. Market mechanisms alone cannot address climate change because they cannot account for intergenerational justice or global equity concerns that require democratic deliberation.

American leadership in democratic renewal could catalyze broader global movements toward post-neoliberal governance models that prioritize public purpose over private accumulation.

Conclusion: Restoring the Moral Algorithm

The systematic inversion of American governance from public service to private extraction represents the core challenge of our historical moment. This transformation has undermined not only democratic institutions but the broader social infrastructure necessary for human flourishing and collective progress.

The documents analyzed throughout this thesis—from Adams' moral algorithm to contemporary analyses of rights discourse and economic policy—converge on a fundamental insight: sustainable human progress requires institutional arrangements that subordinate private accumulation to public purpose. When this relationship is inverted, as it has been in contemporary America, the result is systemic dysfunction across economic, political, and social domains.

The solution requires constitutional-level intervention that restores democratic control over private power accumulation. The amendment strategy outlined here—severing the money-power nexus through constitutional reform—offers the most direct path toward institutional restoration. By removing private wealth from political influence, this approach would enable democratic institutions to address the broader consequences of systematic inversion through normal political processes.

This thesis has demonstrated three crucial points:

Historical Validation: The Founding generation's explicit rejection of corporate power and emphasis on public purpose provides both moral authority and practical precedent for constitutional reform. The American tradition includes robust mechanisms for constraining private power when it threatens democratic governance.

Systemic Analysis: Contemporary American dysfunction stems not from policy disagreements or cultural conflict but from structural transformation that inverts the relationship between public authority and private power. This systematic inversion explains otherwise puzzling patterns across diverse domains—from healthcare costs to political polarization to environmental degradation.

Constitutional Solution: Addressing systematic inversion requires constitutional amendment that restores democratic control over private power accumulation. No lesser intervention can address the structural sources of capture and concentration that generate ongoing dysfunction.

The path forward requires extraordinary political mobilization around constitutional restoration rather than conventional policy reform. This mobilization must transcend partisan divisions by focusing on shared democratic values rather than specific policy preferences. The amendment strategy provides a framework for building such coalitions while creating immediate legal mechanisms for enforcement.

Ultimately, this thesis argues for understanding the American crisis as a constitutional crisis requiring constitutional solutions. The moral algorithm embedded in founding documents provides both the normative framework and practical mechanisms for democratic renewal. Restoring government to its proper purpose—serving the common good rather than private interest—represents not radical innovation but return to foundational principles adapted for contemporary challenges.

The stakes extend beyond American borders because democratic governance faces similar challenges globally. American leadership in constitutional restoration could catalyze broader movements toward post-neoliberal governance models that prioritize human flourishing over capital accumulation. In this sense, constitutional restoration represents both national necessity and global opportunity for advancing human progress through democratic means.

The choice before us is clear: continue the trajectory toward oligarchy and democratic collapse, or mobilize for constitutional restoration that rebuilds government around public purpose. The moral algorithm provides both the destination and the compass for this essential journey.