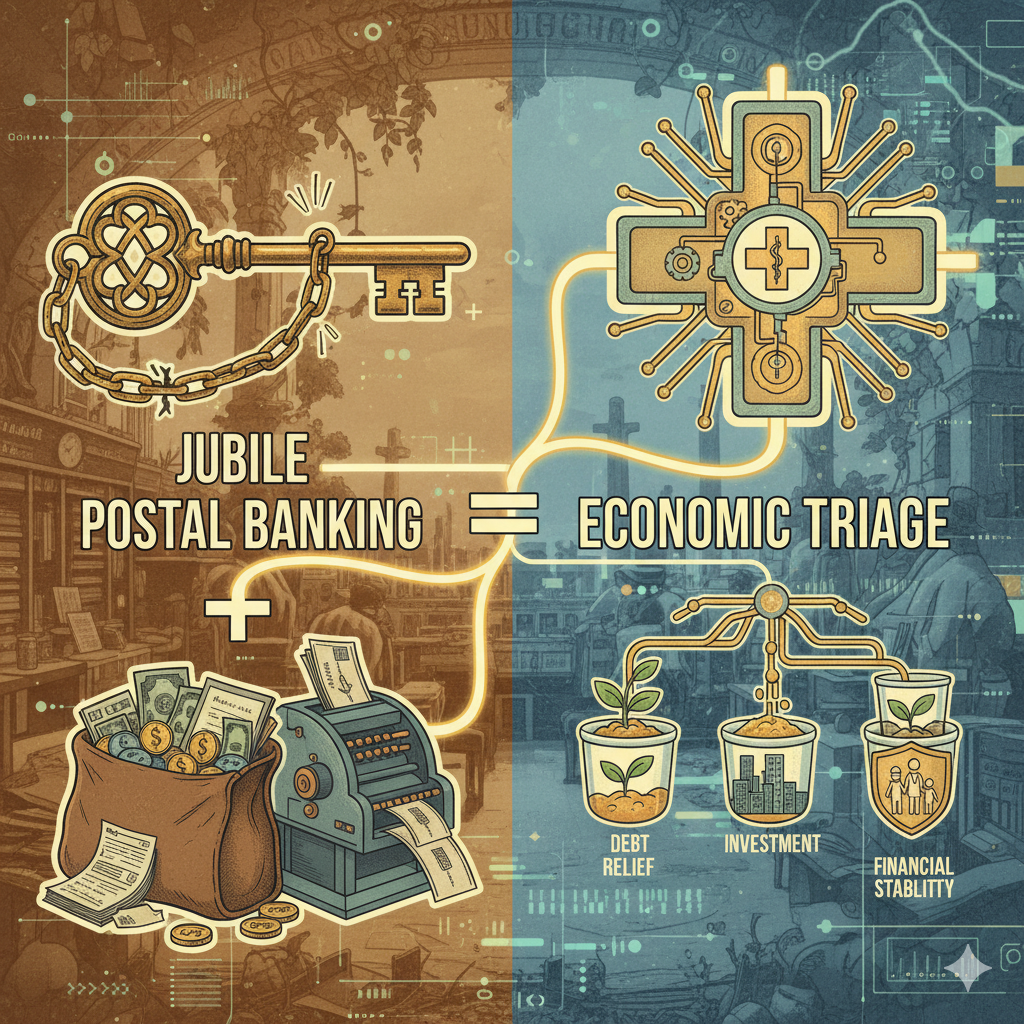

Jubilee + Postal Banking = Economic triage

Each citizen gets $100K in Treasury funds to pay off personal debt and deposit the remainder in a Postal Bank account. This savings backs future self-loans, reducing inequality, boosting money velocity, and ending predatory lending—all via standard public banking mechanics.

Chartalism, Cantillon Effects, and Money Velocity in the U.S. Economy

Introduction

The United States economy today faces persistent wealth inequality, historically low money velocity, and episodes of financial instability. To understand why, we can examine the monetary system through the lenses of Chartalism, the Cantillon effect, and money velocity. These concepts help reveal the root causes (using a "5 Whys" approach) of our current economic reality. We will then analyze a bold policy proposal – a universal $100,000 per citizen transfer with a public Postal Bank – and project its potential effects on inequality, money circulation, and stability. The goal is a comprehensive, up-to-date exploration of why the economy is the way it is, and how the proposed policy might address those underlying issues.

Chartalism and Modern Money Theory

Chartalism, also known as the state theory of money, holds that money’s value derives from government authority – specifically, the requirement that taxes be paid in the state’s currency. In a modern fiat system, the government is the monopoly issuer of currency and must spend money into existence before it can collect taxes. In other words, spending precedes taxation, and taxes serve to create demand for the currency (to avoid tax liability) rather than to fund spending. This Chartalist perspective, revived in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), implies that a sovereign government like the U.S. is not financially constrained in its own currency – the real limit to public spending is the availability of labor, capital, and resources, and the risk of inflation once those real resources are fully utilized.

Under Chartalism/MMT, deficits are not inherently bad; government debt in its own currency is essentially the private sector’s asset (net financial wealth). Money is created “vertically” by government spending and “horizontally” by bank lending, but only the former adds net assets to the private sector. This theory suggests that public policy can use the currency-issuing power proactively – for example, funding a large citizen dividend or job guarantee – as long as it does not push aggregate demand beyond the economy’s productive capacity. Inflation is the key constraint: when the economy nears full employment and output limits, additional government spending can cause demand-pull inflation, which must be managed (e.g. by raising taxes or other measures). In summary, Chartalism provides a framework in which the U.S. Treasury and Federal Reserve could facilitate something like a $100,000 per person transfer without “running out of money”, focusing instead on resource utilization and price stability.

The Cantillon Effect and Inequality

While Chartalism explains how money is created and what gives it value, the Cantillon effect explains who benefits first from new money – and how that can drive inequality. First described by 18th-century economist Richard Cantillon, this effect observes that when new money is injected into the economy, it does not spread evenly to all people. Those closest to the source of money creation (such as big banks, corporations, and investors) get to use the new money before prices rise, reaping outsized gains, whereas those farther away (ordinary workers and consumers) see higher prices before their incomes or liquidity increase. In practical terms, the first recipients of newly created money can buy assets and goods at old prices, while later recipients face the inflation that follows. This tends to widen economic inequality: financial institutions and asset owners benefit, while wage earners lose purchasing power in relative terms.

Recent U.S. economic history provides clear examples of the Cantillon effect. During the response to the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, the Federal Reserve created trillions of dollars through quantitative easing (QE) and other programs. Much of this new money entered the economy via the financial sector – boosting bank reserves, bidding up asset prices (stocks, bonds, real estate), and allowing corporations to refinance or pay off debt. Wall Street and large firms, flush with liquidity, benefited first: they paid down liabilities and enjoyed a stock market boom, while everyday people saw little direct improvement. In fact, many businesses and investors removed money from circulation (using it to deleverage or purchase long-term assets), meaning the broader public eventually suffered inflation (e.g. higher housing and goods prices) without receiving much of the new money – a phenomenon noted as “biflation,” where asset prices soar but consumer purchasing power erodes. In short, policy choices like QE inadvertently “Cantilloned away” a lot of the stimulus: the wealthy gained wealth, while lower-income households mainly got the bill in the form of rising living costs. This helps explain why wealth inequality is so severe today – more on that next.

Wealth distribution in the U.S. is heavily skewed. As of early 2024, the top 1% of households hold about 30% of all wealth, while the bottom 50% hold only 2.5%. This concentration has grown over decades (the top 1% held ~23% in 1989, now over 30%) and has been exacerbated by policies that disproportionately channeled money to the top. The Cantillon effect highlights that how new money enters the economy matters: whether it’s via bank bailouts, asset purchases, or broad-based public spending will determine who prospers. A policy that injects money equally to all citizens (as in the proposed $100k transfer) aims to flip the usual Cantillon pattern – giving the average person direct first access to new money, rather than only banks or insiders. This could have profound implications for reducing inequality.

Money Velocity in the United States

Money velocity measures how fast money circulates – essentially, how often each dollar is spent on goods and services. It is commonly defined as the ratio of nominal GDP to the money supply. A high velocity means money is changing hands frequently (indicating robust economic activity), whereas a low velocity means money sits idle or is hoarded, and the economy is sluggish despite the money supply. In the U.S., money velocity has been on a long decline, and today it languishes near historic lows. For instance, the velocity of broad money (M2) was about 1.39 in late 2024, meaning each dollar was spent ~1.4 times in a year – much lower than in past decades. In the late 1990s, M2 velocity peaked around 2.1–2.2; but it fell steadily after 2000, hitting a record low of 1.13 in Q2 2020 amid the pandemic. Even after the economy reopened, velocity has only inched back up (hovering in the mid-1.3s in 2023–2025). This indicates that despite large increases in the money supply (from Fed easing and deficit spending), much of that money is not actively circulating in purchases of domestically produced goods and services.

Why is money velocity so low? One major factor is the aforementioned inequality and Cantillon dynamics. When more wealth and liquidity concentrate at the top, money tends to sit in investments or savings rather than being spent on everyday consumption. (A billionaire can only spend so much of each extra dollar; the rest might go into stocks or simply remain as excess bank balances.) In contrast, if the same money were in the hands of lower- or middle-income consumers, it would likely circulate faster (paying for groceries, rent, discretionary items, etc.). In this way, extreme wealth concentration drags down velocity – the rich accumulate idle balances while the non-rich lack money to spend, creating a paradox of plenty (high money supply, low turnover). Additionally, the post-2008 era saw banks holding huge excess reserves and corporations stockpiling cash, further dampening velocity. Debt overhang is another culprit: many households devote income to servicing debts (mortgages, student loans, credit cards) rather than spending, which slows the circulation of money. In fact, U.S. household debt remains high at about 68% of GDP as of 2025, a legacy of years of credit-fueled consumption and rising costs. Servicing this debt (which largely flows to creditors and financial institutions) can act like a sink for money that might otherwise boost demand in the real economy.

The low velocity is symptomatic of a broader issue: traditional policy injected a lot of money, but in a way that did not effectively “trickle down” into everyday spending. The proposed Postal Bank policy, by contrast, would directly empower households to spend or pay debts. If every citizen receives funds and many become debt-free with cash in hand, one would expect money velocity to rise – as more people finally have disposable income and pent-up needs to spend on. We will explore that in the policy impact, but first, let’s drill down to the root causes behind the current economic reality using the “5 Whys” technique.

Root Causes of Economic Reality: A “Five Whys” Analysis

At first glance, we see high inequality, low money velocity, and recurring financial instability (crises, bubbles, crashes) in the U.S. economy. Why? We can uncover deeper causes by repeatedly asking “why,” moving from symptoms to underlying structure:

- Why are inequality and wealth gaps so extreme? Because the mechanisms of money creation and economic policy in recent decades have favored capital over labor and the already-wealthy. For example, monetary expansion via banks and markets (QE, low interest rates) boosted asset prices, benefiting the top who hold the majority of stocks and real estate. At the same time, wage growth for the typical worker stagnated and tax policy became less progressive, allowing wealth to concentrate at the top. In short, those closest to new money (banks, corporations) gained first (Cantillon effect), while ordinary people saw little income growth but did face rising asset prices (housing, etc.) that made it harder to get ahead.

- Why did policy choose those channels (banks/markets) to inject money, rather than directly benefiting the public? Because of a combination of institutional design and economic ideology. The U.S. relies heavily on the Federal Reserve and private banks to manage the economy, reflecting a longstanding preference for “market-based” solutions and fear of direct government intervention. When recessions hit, the default response was to cut interest rates and use the Fed to indirectly stimulate spending (through credit and wealth effects) instead of fiscal programs that put money directly in consumers’ hands. Additionally, the prevailing orthodoxy (prior to MMT’s resurgence) treated government deficits as inherently problematic, limiting the use of direct fiscal transfers. This meant stimulus flowed through Wall Street pipes instead of Main Street pockets, by design. In essence, the mainstream economic belief in self-regulating markets and aversion to “printing money” for people led to a reliance on banks as intermediaries, with the unintended consequence of magnifying inequality.

- Why has that orthodox mindset persisted, despite stagnating results? Because it is reinforced by powerful interests and historical narratives. Financial institutions and those benefiting from the status quo have influence over policy and public discourse – their success under the current system is often cited as evidence that the system works (for them, it certainly does). Moreover, memories of 1970s inflation created a political aversion to anything resembling “free money” to the public; instead, policymakers found it more palatable to support financial markets (e.g. bailing out banks in 2008, or corporate bond-buying in 2020) under the rationale of stabilizing the system. The result is a kind of institutional inertia and cognitive capture: economists and officials kept targeting inflation and unemployment with blunt monetary tools, while neglecting the build-up of private debt and inequality. In fact, private debt was largely ignored in orthodox models (which assumed money and credit are neutral in the long run), even as household and corporate leverage soared. This oversight meant growing financial fragility went unaddressed until crises hit.

- Why does high private debt matter for the broader economy (instability and low velocity)? Because excessive debt acts as a drag on spending and a source of fragility. When households are highly indebted, a large chunk of their income goes to servicing loans (interest and principal) rather than consuming goods – this suppresses demand and lowers money velocity. It also makes families vulnerable to shocks (job loss, rate hikes), risking default or bankruptcy. Post-2000, easy credit masked stagnating incomes; but by 2007, households were overextended, triggering a financial crisis when the housing bubble burst. Similarly, corporate debt can fuel investment booms that crash painfully. As economist Hyman Minsky noted, stability breeds complacency and more borrowing until a tipping point. The root cause here is that the financial system was left to expand credit unsustainably, filling the gap that weak wage growth and austere fiscal policy left in consumer demand. In other words, we replaced wage gains with loan growth. This was profitable for banks and kept consumption going for a while, but it set the stage for instability. High debt also meant when the Fed tried to stimulate by lowering rates, it mainly encouraged more borrowing (and asset speculation) rather than broad spending, further entrenching a low-velocity, bubble-prone environment.

- Why were wages stagnating and costs (housing, education, healthcare) rising? This gets into broader structural issues: globalization, technology, weakened labor unions, and policy choices led to weak bargaining power for labor and thus tepid wage growth, even as worker productivity rose. Meanwhile, key living costs soared. These trends meant even before the Great Recession, many Americans lived paycheck-to-paycheck, unable to save – and thus unable to benefit from asset inflation. To maintain living standards, many turned to credit (student loans for expensive college, mortgages for homes in a boom, medical debt for healthcare, etc.). The deeper why here includes deliberate policy choices (deregulation, tax cuts for the wealthy, underinvestment in public goods) that prioritized short-term efficiency or profits over broad-based prosperity. The result is a feedback loop: low wages and high costs force reliance on debt; high debt then locks in low velocity and financial fragility, making the economy overly dependent on continual credit expansion or asset bubbles to sustain growth. This is the reality we find ourselves in: an economy flush with created money yet starved of widely shared prosperity.

In summary, the root causes trace back to how money is created and distributed in our system. The state has the power (as Chartalism notes) to issue money for public purpose, but in practice it ceded much of that power to private credit creation and was timid in using fiscal tools for the common good. The Cantillon effect ensured new money largely enriched those at the top, entrenching inequality. This led to low money velocity (money hoarded by the rich, constrained for the rest) and an economy propped up by debt and asset bubbles – a recipe for periodic crises. Any solution thus needs to directly change the way money enters the economy and who benefits, addressing these structural issues.

The Proposed Policy: Postal Bank + Universal $100k Transfer

Policy Outline: The proposal under examination is as follows – each U.S. citizen would receive a $100,000 transfer from the Treasury, and a new public Postal Bank is established to manage the aftermath. The key conditions and mechanics include:

- Universal Treasury Transfer: Every citizen is granted $100,000 in newly created sovereign money (likely via a one-time increase in public debt or direct money issuance). This is akin to a massive “helicopter money” drop or modern debt jubilee. Importantly, recipients must first use the funds to pay off any personal debt (credit card balances, student loans, mortgages, auto loans, etc.). This immediately wipes out (or at least greatly reduces) household debts nationwide.

- Public Savings Accounts: After clearing personal debts, any remaining funds from the $100k are deposited into a savings account at the Postal Bank in the individual’s name. For example, a person with $30,000 of debt would pay that off and then put the remaining $70,000 into their Postal Bank savings. Someone with no debt would deposit the full $100k. These deposits collectively form a large pool of household savings held in a public institution.

- Postal Bank and Self-Funded Credit Lines: The Postal Bank (run through local post office branches or a federal online banking system) isn’t just a passive vault – it will leverage these deposits to extend credit. Each citizen’s deposit effectively backstops their own line of credit. In practical terms, the bank can create new loans (deposits) for the person, up to the amount of their saved balance, using that balance as collateral. This means if a citizen needs a personal loan in the future (for a car, home improvement, etc.), the Postal Bank can lend them money against their own savings, at low interest, rather than them needing to go to a payday lender or run up a credit card. Essentially, people will be borrowing from themselves (with the public bank as the facilitator), turning their savings into a self-funded credit line.

- Standard Accounting (No Magic): The proposal emphasizes that all this operates within normal banking principles. When the Postal Bank makes a loan, it creates a deposit (just as private banks do) – so money supply can expand as needed to support lending. The Postal Bank would hold reserves at the Fed and meet capital requirements like any bank, ensuring it has enough equity backing and adheres to regulations. Loan repayments would go back to reducing the borrower’s liability and replenishing their available savings/credit. In short, the bank follows “loans create deposits” and uses the Fed’s payment system for settlements, just as private banks do, but the lending risk is secured by each person’s own collateral and ultimately by the sovereign’s support. This keeps the system stable and accountable.

- Capital and Regulatory Constraints: To prevent abuse or over-leveraging, the Postal Bank would operate with prudent constraints. Since loans are backed by the depositor’s own saved funds, default risk is minimal (the bank could automatically deduct from the person’s deposit if needed, much like a secured loan). The bank’s ability to lend might be capped by a ratio (e.g. perhaps it can only lend up to the amount of actual deposits held – a 100% reserve or full collateral model – which is far more conservative than private banks that lend many times their deposits). Additionally, post-policy regulations could restrict traditional banks from returning to predatory high-interest lending, especially now that every citizen has access to low-cost credit. This ensures discipline: the Postal Bank won’t create a reckless credit boom because loans are self-collateralized and profit motive is not driving lending (the aim is public service, not maximizing interest income).

In essence, the policy is a one-time reset of household finances combined with the creation of a public banking option for the future. Every American emerges from the policy debt-free (or much less indebted) and with some positive net worth in savings. They also gain a form of sovereign wealth stake – not exactly like a traditional sovereign wealth fund, but individually held capital that came from the nation’s fiscal capacity. Unlike a basic income meant for spending, this transfer is structured to repair balance sheets and bolster long-term financial security. Let us now analyze the expected effects of such a dramatic policy.

Expected Effects on Inequality, Velocity, and Stability

If implemented, this dual policy (debt jubilee + postal banking) would have far-reaching consequences. Below we break down the key anticipated impacts, linking them to the theoretical principles discussed and providing a projected post-policy scenario:

- Immediate Reduction in Inequality (Wealth and Income): This plan would be fundamentally redistributive in absolute dollar terms (everyone gets $100k) and even more so in relative terms. For a low-wealth household – say the bottom 50% of Americans who currently average only a few thousand dollars in net worth – a $100,000 boost is transformational, increasing their wealth manyfold. For a top 1% household, $100k is a drop in the bucket. Thus, the wealth share of the bottom 50% would climb significantly. (Currently the bottom half hold only ~2.5% of U.S. wealth; after the transfer, they would hold a much larger portion – by our estimates, potentially around 6–10% of wealth, roughly tripling their share – because each of those ~125 million adults gets $100k, totaling trillions in new assets for that group.) Inequality of net worth would therefore sharply decline overnight. Every citizen becomes a saver, with a nest egg or stake they didn’t have before. This democratization of wealth also means more people can invest in their future (education, starting a business, buying a home) without needing to inherit money or take on burdensome debt. Income inequality would also likely fall. By eliminating debt payments, a larger portion of people’s earnings become free for personal use, effectively raising disposable income for the formerly indebted. Many high-interest obligations (e.g. payday loans or credit cards at 20% APR) functioned like regressive drains on income; wiping those out is akin to a significant income boost for lower earners who disproportionately paid those fees. Moreover, with savings in hand, individuals have more bargaining power – they are less desperate and can wait for better job opportunities or demand better pay (potentially putting upward pressure on wages at the low end). Overall, expect a more egalitarian economy: the Gini coefficients for wealth and income would improve as the policy acts like a giant leveling windfall from the public purse.

- Elimination of Household Debt and Interest Burdens: The requirement to pay off personal debt first means the U.S. would undergo a one-time mass deleveraging of the private sector. Trillions in household liabilities (mortgages, student loans, consumer credit) would be wiped out in one sweep. This is effectively a debt jubilee, something proposed by economists like Steve Keen, who argued it’s the only way to truly reduce debt overhang without crushing the economy. Freed from monthly debt service, families would experience a substantial increase in monthly cash flow. For example, a household paying $800 in student loan and credit card payments per month would now keep that $800 to either save or spend. This translates into higher consumer spending capacity (boosting demand) and/or greater financial resilience (ability to save for emergencies). Crucially, by removing the weight of interest payments (often to predatory lenders), the policy stops the wealth transfer from borrowers to creditors that was ongoing. It’s noted that fringe financial fees and interest can consume up to 10% of an underserved household’s income – effectively a poverty trap. With the jubilee, that “tax” on the poor is gone, allowing them to build wealth.

- Rise in Money Velocity and Consumer Demand: With debts cleared and cash in hand, many households would likely increase their spending, especially those who had been liquidity-constrained. We would expect a surge in demand for goods and services – people might finally replace that old car, move to better housing, eat out more, etc. Money velocity should accelerate as this newly empowered middle and lower class actually uses their money, as opposed to it stagnating in bank accounts of the rich. An important nuance: not all of the $100k windfall will be spent immediately – in fact, by design much of it goes into savings – but even the act of paying down debt is part of the circulation (it transfers money to the banking sector, as we’ll discuss). And going forward, the removal of debt-service burdens means higher disposable income each month, which likely translates to steady increases in consumption over time. To quantify the potential effect: total U.S. consumer spending might jump significantly in the short term. If even a fraction of the aggregate $8–10 trillion in leftover cash (after debt payoff) is spent in the first year, that’s a massive stimulus. For instance, if $2 trillion of it is spent on consumption or investment, that alone is ~8% of GDP. This stimulus would drive robust economic growth, potentially pushing GDP higher for a few years. In turn, higher GDP absorbs some of the shock of higher public debt – as one model of a debt jubilee found, the GDP boost helps reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio compared to doing nothing. In other words, while the government’s debt would rise by the cost of the program, the economy’s size would also increase, making the public debt burden more sustainable than feared (especially if interest rates remain moderate). Put simply, forgiven private debt is partly offset by new public debt, but the overall economy strengthens.

- Inflation Impact: Likely Moderate and Manageable: A natural concern is whether injecting such a colossal sum (on the order of $100k × ~250 million adults = $25 trillion) would ignite runaway inflation. The proposal asserts it can be done “without inflationary impact.” While zero inflation is unlikely (there will be some pricing pressure in certain sectors), there are factors that mitigate the effect:In sum, a temporary uptick in inflation is possible – even likely in areas like housing or consumer goods that see sudden demand. But this is not hyperinflation territory, because we’re largely restructuring balance sheets rather than purely doubling everyone’s spendable income overnight. Empirical support: during COVID, the U.S. injected trillions in fiscal stimulus and saw inflation rise to ~9% at peak, now receding. The jubilee’s structure channels much of the money to balance sheet repair and future security, meaning the immediate spending wave might be less than COVID stimulus which was largely direct cash with no strings. Furthermore, any inflation that does occur must be weighed against the enormous reduction in private costs (no loan payments, etc.) – overall purchasing power for essentials might actually improve for most citizens even if prices tick up somewhat, because their debt burden is gone. Nonetheless, careful calibration and perhaps phasing the rollout could be wise to avoid demand overshooting supply.

- Debt Payoff vs. New Spending: A huge portion of the money would go to pay off existing loans rather than immediately chasing new goods. Paying off a loan, in economic terms, destroys that bank-created money (the loan’s principal) as it is removed from the money supply. In this case, new government-created money replaces old private credit. For example, if $17 trillion of the $25T is used to cancel debts, that’s $17T that was already counted in money supply (as bank loans) being extinguished. The net new money injection is the remainder that ends up in savings (say around $8T in our earlier estimate). An $8T net addition is still huge, but it’s smaller than $25T, and it goes initially into savings accounts rather than hot circulation. So the immediate surge in money available to spend is much less than the headline figure.

- Increase in Supply and Investment Potential: With improved finances, there’s potential for a supply-side response: entrepreneurs can invest, people may start businesses, and labor force participation might increase (as folks have means to acquire skills or move to where jobs are). If the policy is accompanied by supportive measures (like incentives to boost housing construction, given many may want to buy homes), the economy’s productive capacity can expand to meet the higher demand, tempering inflation. Also, the Postal Bank credit lines mean many purchases might be done via loans that are repaid, keeping an equilibrium rather than pure cash chasing goods.

- Monetary Policy and Reserves: Banks will end up with a flood of reserves from all the loan payoffs. They won’t suddenly lend it out (since people now have less need to borrow from private banks), so the risk of an out-of-control credit boom is low. The Fed can adjust interest on reserves to keep banks from aggressively trying to create new risky loans. Essentially, the central bank retains tools to soak up excess liquidity or cool demand if inflation starts running too hot. Since MMT-oriented thinking would view taxes as a way to counter inflation, the government could later impose modest taxes on the wealthy (who benefited least from the transfer) if demand needs reining in. Political will aside, technically inflation can be managed by adjusting fiscal and monetary dials once the beneficial effects (debt freedom, etc.) are achieved.

- Impact on the Banking and Financial Sector: Private banks would undergo a dramatic shift. On one hand, they receive a huge inflow of cash from all the loans being paid off. This injects liquidity into the banking system – banks’ balance sheets would suddenly have far more reserves (or treasury credits) instead of loan assets. Bank solvency would generally improve (since loans are paid at full face value, no defaults). However, banks would also lose future interest income from those canceled loans. For example, a bank that had a 5% mortgage will no longer earn that interest for the remaining years – instead, it now holds cash (reserves) earning the Fed’s interest on reserves (which is typically lower). In aggregate, the banking sector becomes safer but less profitable in its old lines of business. This is intentional: the policy essentially squeezes out predatory and high-interest lending, as citizens no longer need to rack up 20% APR credit card debt or payday loans when they have their own savings and Postal Bank access. Private lenders would be forced to compete by offering better terms or pivoting to more productive lending (like business loans, which might still be in demand). The Postal Bank, as a public option, would likely offer low-interest loans (since they are secured by deposits) – this undercuts the usurious rates that payday lenders or subprime consumer finance chargedamericanprogress.org. We can expect the payday lending industry and similar fringe services to wither, as millions of Americans who were unbanked or underbanked now have an account and credit line at the USPSamericanprogress.org. This is a huge plus for financial inclusion: historically, lack of access to banking has hurt low-income and minority communities, forcing them to rely on check cashers and loan sharks. Postal banking would bring affordable financial services to every community, since the USPS network reaches everywhere. By providing basic checking, savings, and credit at nominal cost, it automatically shields vulnerable groups from predatory practices that siphoned wealth (for instance, extremely high interest rates – 400%+ APR – on payday loans effectively taxed the poor). Eliminating those draining costs is identified as a necessary step in tackling the root causes of inequalityamericanprogress.org. There is a potential downside for the financial sector: with less consumer borrowing and a big chunk of existing loans paid off, banks might face a contraction in their loan portfolios. They will have excess funds that need to be put to work – possibly leading them to lower lending standards or chase speculative investments if not guided. To avoid re-inflating a credit bubble, regulators could enforce stricter lending standards going forward (as Steve Keen suggests: curbing loans for pure asset speculation and encouraging loans for productive purposes). Banks could focus on financing businesses, infrastructure, and innovation – things that raise productive capacity – rather than over-lending for, say, luxury real estate or stock buybacks. Meanwhile, if people have more equity (e.g. owning a home outright or with a smaller mortgage), the financial system overall becomes more stable – fewer defaults, less risk of a housing crash, etc. The financial sector’s role would shift from extracting rents to facilitating genuine investment. While bank profits might initially dip, a healthier economy with more demand for business credit could open new lending opportunities. The government might also issue “jubilee bonds” or similar to give banks a safe asset to earn interest on, compensating some lost income (Keen’s proposal included this to get banks on board).

- Household and Macroeconomic Stability: By vastly improving household balance sheets, the policy would likely make the economy more stable and resilient in the long run. Consider financial crises: they often start with too much private debt and an inability to pay. Here, that risk is slashed. Households now have cushion (savings) and no high debt, so a downturn would be less likely to spiral into mass defaults. People could handle shocks better – using savings or Postal Bank credit lines to get through tough times. Poverty and stress would decline, as everyone has a financial floor underneath them. The mental and physical health benefits of relieving debt stress are hard to quantify but very real. Furthermore, with a sovereign wealth stake, every citizen effectively has a bit of capital that grows with the economy (if properly managed). We might analogize it to Alaska’s Permanent Fund dividend, but on a one-time larger scale – giving people a direct share of the nation’s wealth. From a macro perspective, shifting some private debt to public debt could actually reduce the risk of financial collapse. Government debt (especially in a monetarily sovereign nation like the US) is far more durable – it doesn’t have a liquidation trigger, and the Fed can always support it. Private debt, in contrast, can cause bankruptcies and bank failures if not paid. So trading private for public debt, within reason, reduces systemic risk. Additionally, a broad-based increase in consumer demand (from debt-free households) makes recessions less likely; velocity rising means money is circulating to businesses, which can then hire and invest. There is a self-reinforcing effect: when people spend, businesses earn more and can pay workers more, who then spend – a virtuous cycle perhaps rekindled. One must acknowledge the moral hazard question: Does wiping out debt and handing out cash reward bad actors or encourage future reckless borrowing? The plan tries to minimize this by including everyone (so it’s not singling out only those who borrowed irresponsibly – even the thrifty get $100k). Also, since it’s a one-time reset, the expectation is that stricter financial regulation post-jubilee prevents a return to status quo ante. People will know this was a unique event, not to be repeated on a whim. And because the Postal Bank provides a safety net of credit, individuals won’t need to turn to predatory loans in the first place, reducing future risky debt behavior. Essentially, the economy moves to a new footing where credit serves the public, rather than the public serving credit.

- Projected Post-Policy Scenario (One Year Later): Let’s envision the economy a year or two after implementation. Every citizen has been empowered with $100k: all student loans are gone, credit cards paid off, mortgages paid down or eliminated. Household debt-to-GDP plummets from ~68% to near 0% for a time (some mortgages larger than $100k might remain partially, but in aggregate a huge drop). The bottom 50% of Americans, who had virtually no wealth, now collectively hold trillions in deposits. The top 1% see their share of wealth drop (e.g. from ~30% to perhaps ~25%) because the total pie of private wealth increased and was distributed evenly. Consumer spending surges in areas like durable goods, cars, home improvement – GDP in the first full year post-transfer grows at a blistering pace (perhaps the fastest on record) due to the one-off stimulus effect. Unemployment falls as businesses staff up to meet demand. Wages could start rising more broadly because labor can be choosier (with savings to fall back on, fewer workers accept rock-bottom pay). Small business formation jumps up – many people finally have startup capital or feel secure enough to take entrepreneurial risks, which fosters innovation and job creation. The federal government’s debt has increased by the cost of the program (~$25T). As a result, public debt/GDP is higher. But thanks to the growth spurt in GDP, it’s not as high as one might have feared in ratio terms. Moreover, interest rates remain under control because the Fed anchors them (possibly even buying some of the new Treasury issuance as it did during QE). There’s political debate but also public satisfaction – after all, everyone received a substantial benefit, and social outcomes improved (poverty and homelessness markedly decline, etc.). Inflation in the initial year may have spiked in certain sectors: for instance, housing prices likely rose as many new buyers entered the market with down payments ready. To counter this, the government could invest in accelerating homebuilding or impose measures to cool speculation. Overall consumer price inflation might run a bit above trend (say 4–6% for a year) but then stabilizes. Crucially, wage growth for once might outpace inflation, meaning the average American is better off in real terms. The Fed remains vigilant but does not need to induce a recession, since much of the demand was met by increased supply and one-off price level adjustments. Socially, the country experiences a sense of reboot. Think of it as giving everyone a clean slate and a stake: young adults start their working lives unencumbered by student debt, middle-aged folks can actually save for retirement or their kids’ education now, and older folks can pay off medical debts or mortgages, gaining peace of mind. With the Postal Bank accounts, financial inclusion is near-universal – millions who previously had no bank now use the Postal Bank, which offers low-cost services. Communities of color, often targeted by high-cost financial services, particularly benefit from the public banking option and the wealth transfer, beginning to close the racial wealth gap. The Postal Bank itself likely becomes a trusted public institution; it could even expand to offer low-fee checking for everyday use, further undercutting exploitative fees (this aligns with proposals to let USPS offer basic banking to underserved areas). On Wall Street, banks adjust to a new reality. Some consolidation might occur; with consumer lending less profitable, banks focus on commercial lending, wealth management, or other services. Their balance sheets are actually stronger (lots of old bad debts gone), so the risk of a banking crisis is low. They hold a lot of safe assets (Treasuries or reserves) now. Interest rates may be somewhat higher if the government borrowed to fund this (more Treasury supply), but with the Fed’s coordination and the economic boom, markets handle it fine. Investors might initially worry about inflation, but seeing it moderate and the economy’s robust productivity (perhaps spurred by new investment and a healthier workforce), confidence returns.

In a sense, this policy is a bold application of Chartalist/MMT principles – using the government’s monetary power to reset private balance sheets and address inequities directly. It avoids the Cantillon effect by giving everyone the same starting boost (no one is “closer to the faucet” – the faucet was opened above the whole population equally). By doing so, it aims to increase the velocity of money in a healthy way: money flows through productive channels (consumer spending, real investment) rather than pooling in unproductive ones (excess reserves, speculative bubbles). The “five whys” root causes are addressed: lack of purchasing power at the bottom (solved by direct distribution), excessive private debt (solved by jubilee), financial exclusion (solved by postal banking), and the old ideology of trickle-down (replaced by a proactive public boost).

To be sure, such a dramatic intervention would come with challenges – from political feasibility to execution details – but our analysis suggests that the concept, rooted in sound accounting and economic reasoning, could achieve its intended goals. It would create a more equitable, dynamic economy with broadly shared prosperity, higher money circulation, and a more stable financial system. As one economic study noted, the only durable way out of a debt trap is to write off the debt and start anew – this policy does exactly that, while also providing the tools (savings and public credit access) to avoid falling into the same trap again.

Conclusion

The United States stands at a crossroads where the old playbook of indirect stimulus and debt-fueled growth has shown its limits: wealth inequality is extreme, money sits idle at the top while productive Main Street activity lags, and the system’s fragility erupts in crises periodically. By examining the situation through Chartalism, we learned the sovereign government can afford bold action; through the Cantillon effect, we saw that who gets new money matters for fairness; through money velocity, we gauged the malaise in the real economy. Digging into root causes revealed a need to change the very plumbing of our financial system.

The proposed Postal Bank and $100k per citizen policy directly targets those root causes. It uses the federal balance sheet to enrich the private sector broadly (a “people’s QE”), flips the script on money distribution, and builds an inclusive public banking infrastructure for the future. Our analysis indicates this could substantially reduce inequality (potentially giving the lower 50% of Americans a combined trillions in wealth), boost economic demand and growth without uncontrolled inflation, and lead to a more stable, less debt-burdened society. It represents a one-time reboot of the economy’s operating system, after which new rules (capital constraints, lending guidelines) keep things running smoothly.

In a way, it hearkens back to historic resets (like post-WWII debt resets, or ancient jubilees) but via modern monetary institutions. It shows what is possible when policy is guided by an updated understanding of money – one that prioritizes public purpose and broad prosperity over preserving outdated models. While ambitious, such a plan embodies the idea that economic policy should serve the many, not the few, and that sometimes the most direct solutions (give people money, cancel their debts) can be the most effective. The U.S. economy, rejuvenated by this approach, would likely see money changing hands faster, work paying off more fairly, and fewer families lying awake at night under the shadow of debt. That is a vision of economic reality very different from today’s – and perhaps one worth striving for, now that we have traced why things are broken and how we might fix them.

Sources:

- Wray, L. R., Kelton, S., et al. Modern Monetary Theory – core tenets of Chartalism (government as monopoly currency issuer).

- Innes, A. (1914). Credit Theory of Money – money as a government debt redeemable by taxation.

- Wikipedia (2024). Wealth inequality in the United States – top 1% holds ~30.5% of wealth vs bottom 50% only 2.5%.

- Glint Pay (2023). “Understanding the Cantillon Effect” – how first recipients of new money benefit, widening inequality.

- First Digital (2021). “The Cantillon Effect” – uneven diffusion of money, relative prices, and why stimulus via banks led to asset inflation (Wall Street) but limited broad benefit.

- Federal Reserve Economic Data – M2 Money Velocity was ~1.39 in Q4 2024, down from ~2.19 in 1997 and hit a low of ~1.13 in 2020.

- FRED (2025). Household Debt to GDP – U.S. household debt ~68% of GDP in Q1 2025.

- Keen, S. (2020). “Modern Debt Jubilee” – proposal to give everyone money to pay down debt; private debt reduction funded by government-created money.

- Metapolis (2020). A Modern Debt Jubilee – only debt write-offs have historically reduced debt overhang; Jubilee swap of credit debt for fiat money can lower private debt/GDP while only modestly raising public debt/GDP (due to GDP stimulus).

- Center for American Progress (2020). Postal Banking to Address Inequality – postal banking would provide low-cost services, reduce reliance on predatory lenders, and is necessary to tackle root causes of inequality

- U.S. Federal Reserve & FDIC data via CAP – fringe financial services charge up to 400–600% interest, costing unbanked households ~10% of income, illustrating the burden that postal banking could remove.

Citations

Creating a Postal Banking System Would Help Address Structural Inequality - Center for American Progress

https://www.americanprogress.org/article/creating-postal-banking-system-help-address-structural-inequality/

Here’s a mitigation-focused FAQ that addresses the most common concerns and red flags associated with the $100K Postal Banking and debt payoff policy:

💬 FAQ: Risk Mitigation for the $100K + Postal Banking Policy

❓Won’t this cause runaway inflation?

No. The $100K isn’t new consumption money, it’s largely a debt swap. Most of the transfer cancels existing liabilities (credit cards, student loans), reducing net private sector debt. Remaining savings are not spendable cash, but a credit buffer within the Postal Bank. Inflation risk is minimal compared to traditional stimulus.

❓Is this a giveaway for irresponsible borrowers?

No. Everyone gets the same amount, and the policy requires paying down verified debts first. That includes responsible debt like student loans, mortgages, or medical debt. The policy corrects systemic imbalances, not moral failings.

❓Why would responsible savers benefit?

They receive the full $100K. With no debt, they immediately gain a public credit line secured by their own savings, usable for major purchases, education, or emergencies. They also benefit from a more stable economy and higher overall demand.

❓How do you prevent fraud, like fake debts?

The Treasury will partner with the CFPB, IRS, and credit bureaus to verify legitimate debts. Strict documentation and real-time settlement protocols will be required. Fraudulent actors will face penalties and repayment clawbacks.

❓Won’t financial institutions fight this?

Private lenders will resist, but their bad business models (e.g., predatory lending, payday loans) are the problem. This policy doesn’t ban private credit, it simply gives citizens a public option, much like public schools or Medicare.

❓What about constitutional or legal challenges?

The program would be authorized through Congressional legislation, using Treasury’s existing disbursement and tax authority. Debt payoff conditions are no more restrictive than how current tax credits or stimulus funds are used. Legal review will accompany all phases.

❓Won’t markets panic at Treasury issuing trillions?

Treasury would likely fund the program using long-term bonds, possibly supported by Federal Reserve liquidity facilities. Phasing and automatic stabilizers would limit macro shocks. Investors crave safe, long-term assets like U.S. debt, especially in a downturn.

❓Could this trigger bubbles in housing or stocks?

Postal Bank credit will be targeted and capped. Loans must be backed by each citizen’s own stored balance, preventing credit explosions. Capital requirements and use restrictions (e.g., no margin trading) can prevent asset speculation.

❓What if people just withdraw and spend the money?

They can’t. After debt repayment, the remaining balance must be held at the Postal Bank and is only usable as collateral for personal loans. It’s a self-funding savings-credit hybrid, not a cash giveaway.