Gun Violence: From Symptoms to Systemic Solutions

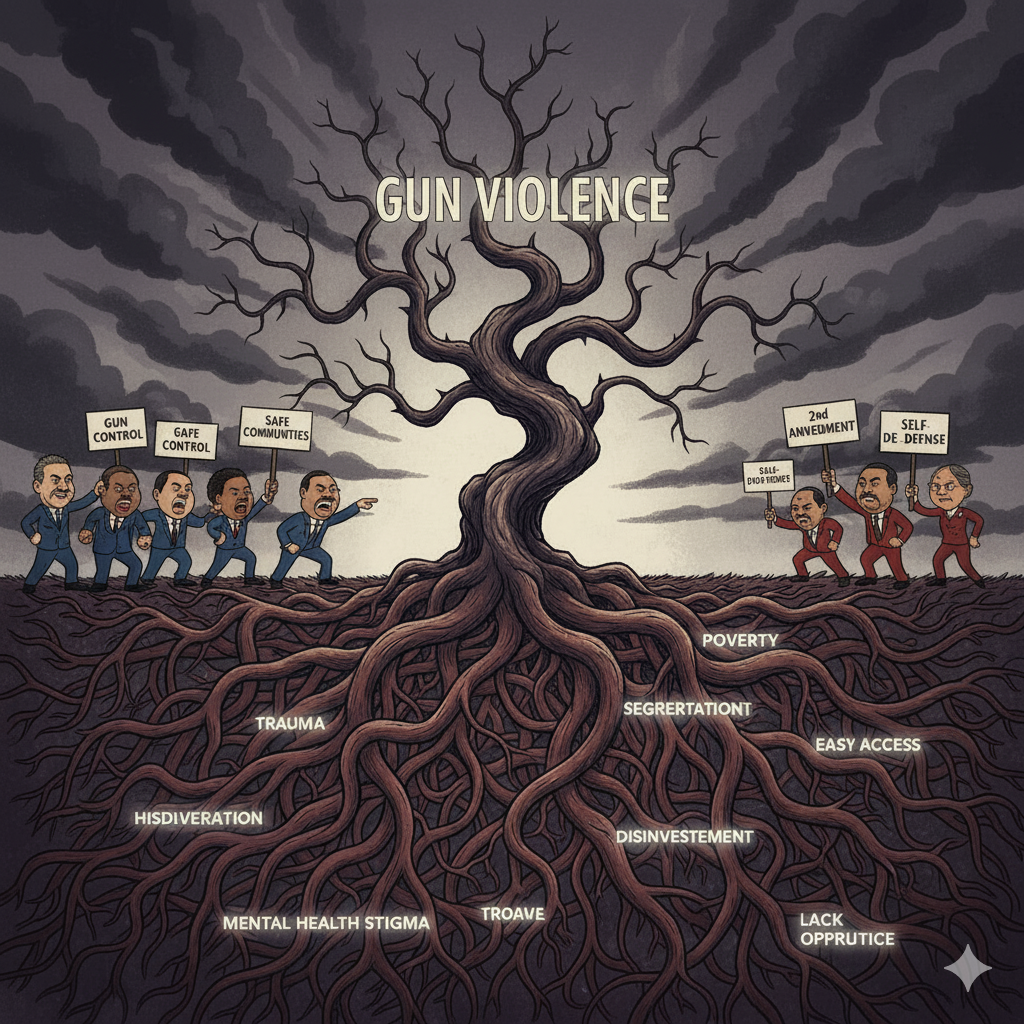

Beyond debates on guns and mental health, this article explores the hidden roots of violence. Using a "5 Whys" analysis, it reveals how systemic inequality fuels violence and proposes Universal Basic Income (UBI) as a foundational solution for lasting safety.

Understanding the Hidden Roots of Gun Violence in America

How asking "why" five times reveals the systemic forces driving violence—and points toward real solutions

When a mass shooting dominates headlines, the public conversation typically follows a predictable pattern. We debate gun laws versus mental health. We argue about security measures versus constitutional rights. We focus intensely on the individual perpetrator, their background, their motives, their warning signs.

But what if we're looking in the wrong place entirely?

Imagine you're a doctor treating a patient with a persistent fever. You could focus solely on bringing down the temperature with medication and that might provide temporary relief. But a skilled physician knows to ask deeper questions: What's causing this fever? What underlying infection or condition is creating these symptoms?

The same principle applies to violence in our communities. The shootings, the homicides, the daily gun violence that rarely makes national news, these are symptoms of deeper systemic conditions that we rarely examine with the same urgency we bring to the immediate crisis.

The Power of Asking "Why"

There's a problem-solving technique used in engineering and business called the "5 Whys"—a simple but powerful method for getting to root causes. Instead of stopping at the obvious answer, you keep asking "why" until you uncover the fundamental drivers of a problem.

Let's apply this lens to gun violence, moving beyond the surface-level explanations toward the forces that actually shape whether communities experience high or low rates of violence.

Why #1: Why do people commit gun violence?

The immediate factors are well-documented: access to firearms, exposure to violence, and unsafe environments. Someone who grows up witnessing domestic violence, neighborhood shootings, or community trauma faces dramatically higher risks of both perpetrating and experiencing violence themselves.

But this raises the next question...

Why #2: Why is exposure to violence so prevalent in certain communities?

Here we encounter what researchers call "concentrated disadvantage", the clustering of multiple risk factors in the same geographic areas. Families struggle with poverty, unstable housing, unemployment, and limited access to quality education or healthcare.

In these environments, violence often becomes normalized as a means of resolving conflicts, gaining respect, or protecting oneself. What sociologist Elijah Anderson termed the "code of the street" emerges, informal rules where violent retaliation becomes expected, even necessary for survival.

But why do these conditions persist in some places while other communities thrive?

Why #3: Why do environments of concentrated disadvantage exist?

This is where we encounter structural inequalities, systems and policies that systematically concentrate opportunity in some places while limiting it in others. Residential segregation separates communities by race and class. Disinvestment in certain neighborhoods reduces access to quality schools, healthcare, and economic opportunities. Discriminatory practices in hiring, lending, and policing create additional barriers.

These aren't accidents of geography or individual choices, they're the predictable results of specific policy decisions made over decades.

Why #4: Why do these structural inequalities persist?

Here we reach the historical and policy roots. Redlining policies that denied mortgages to certain neighborhoods. Urban renewal programs that destroyed established communities. Educational funding systems that tie school quality to local property values. Criminal justice policies that criminalized poverty and addiction rather than treating them as public health issues.

"The past is never dead. It's not even past." William Faulkner

These historical decisions created what researchers call "path dependence", where past choices constrain future options, making change increasingly difficult without deliberate intervention.

Why #5: Why haven't we broken these cycles through intervention?

Finally, we reach perhaps the most important question: why do our current approaches fail to address these root causes?

Fragmented responses treat symptoms in isolation rather than addressing underlying systems. Punitive approaches focus on punishment after violence occurs rather than prevention before it starts. Short-term thinking driven by political cycles interrupts the sustained, multi-generational effort required for systemic change.

Most critically, we've treated violence as primarily a criminal justice problem rather than what public health experts recognize it to be: a preventable epidemic with identifiable risk factors and evidence-based solutions.

The Science Behind the Symptoms

This systems-level understanding isn't theoretical, it's grounded in decades of rigorous research across multiple disciplines.

The Biology of Trauma

Studies on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) reveal how trauma literally rewires the developing brain. Children who experience abuse, neglect, or community violence show measurable changes in brain regions responsible for impulse control, threat assessment, and emotional regulation.

This isn't a matter of weak character or bad choices, it's neurobiology. Chronic stress and trauma create what researchers call "toxic stress," which disrupts healthy brain development and increases vulnerability to violence, addiction, and mental health challenges throughout life.

The Geography of Opportunity

Neighborhood research shows that where you grow up significantly impacts life outcomes, independent of family characteristics. Children in high-opportunity neighborhoods—those with quality schools, economic mobility, and low violence rates—fare dramatically better than identical children in low-opportunity areas.

Harvard economist Raj Chetty's research demonstrates that moving children from high-poverty to low-poverty neighborhoods reduces their likelihood of single parenthood by 28% and increases their lifetime earnings by $302,000. The ZIP code where a child grows up can be more predictive of their future than their individual talents or family structure.

The Social Ecology of Violence

Violence doesn't occur randomly, it follows predictable patterns related to social cohesion and collective efficacy. Communities where neighbors know each other, where residents feel empowered to intervene in problems, and where institutions (schools, police, businesses) are trusted and effective experience significantly lower violence rates.

Conversely, communities where social bonds are weak, where institutions are viewed as illegitimate or harmful, and where residents feel powerless to affect change become vulnerable to violence as an alternative means of social control.

The Moral Algorithm: Rediscovering America's Founding Purpose

Before we explore specific solutions, it's worth examining the moral foundation that should guide our response to systemic violence. Buried within America's founding documents lies what we might call a "moral algorithm", a clear formula for evaluating government action.

John Adams, one of our nation's architects, articulated this principle with remarkable clarity:

"Government is instituted for the common good; for the protection, safety, prosperity and happiness of the people; and not for the profit, honor, or private interest of any one man, family, or class of men and to reform, alter, or totally change the same, when their protection, safety, prosperity and happiness require it."

This isn't merely historical rhetoric, it's a systems-level framework for governance that speaks directly to our current crisis. Adams understood something profound about institutional purpose: government exists to create conditions where all people can flourish, and when it fails to do so, we have not just the right but the obligation to restructure it.

Applying the Moral Algorithm to Modern Challenges

When we apply Adams' criteria to our "5 Whys" analysis of gun violence, the implications become clear:

Protection and Safety: Our current approach, which allows systemic conditions that predictably generate violence to persist while focusing primarily on punishment after harm occurs, fails this test. True protection requires addressing the environmental factors that create danger in the first place.

Prosperity: When concentrated poverty, limited economic mobility, and structural disinvestment characterize entire communities, we're not meeting Adams' standard. Prosperity cannot be reserved for some while others struggle with basic survival, because, as our analysis shows, that inequality ultimately threatens everyone's safety.

Happiness: This isn't about individual contentment, but about what political philosophers call "civic flourishing", the ability of communities to thrive socially, culturally, and economically. Communities plagued by violence, trauma, and disinvestment cannot achieve this fundamental goal of governance.

The moral algorithm demands that we ask: Are our current systems serving these foundational purposes? If not, what changes does protection, safety, prosperity, and happiness require?

From Private Interest to Common Good

Adams' emphasis on avoiding "profit, honor, or private interest" is particularly relevant to how we've approached violence prevention. Too often, our responses serve narrow interests rather than the common good:

- Political interests that prioritize appearing tough on crime over evidence-based prevention

- Economic interests that profit from incarceration, weapons sales, or maintaining inequality

- Ideological interests that prefer simple explanations to complex systems analysis

The moral algorithm redirects our attention toward what actually works to protect and prosper communities, regardless of whether those solutions align with particular political or economic interests.

When we examine policies like Universal Basic Income through this lens, we're asking: Does this intervention serve the common good by enhancing protection, safety, prosperity, and happiness for the people? The evidence suggests it does, not because it's politically expedient or ideologically satisfying, but because it addresses the systemic conditions our analysis reveals as violence drivers.

The Constitutional Imperative for Systemic Change

Adams' framework also provides constitutional legitimacy for the kind of comprehensive reform our analysis suggests is necessary. When he writes about the obligation "to reform, alter, or totally change" systems that fail to serve their purpose, he's not describing revolution, he's describing adaptive governance.

The persistence of violence-generating conditions in American communities represents exactly the kind of systemic failure that demands structural response. Incremental adjustments to a fundamentally flawed approach don't meet the moral algorithm's standard when "protection, safety, prosperity and happiness require" more substantial change.

This constitutional perspective reframes comprehensive interventions like UBI not as radical departures from American values, but as returns to America's foundational principles. We're not imposing foreign ideologies—we're fulfilling the moral promises embedded in our founding documents.

Beyond Individual Solutions: A Systems Approach

Understanding these root causes, and their alignment with our nation's moral foundation—transforms how we think about solutions. Instead of focusing solely on individual interventions, therapy for troubled youth, arrests for perpetrators, security measures for potential targets, we can address the environmental conditions that produce violence in the first place.

Community-Level Interventions

Violence intervention programs like Cure Violence treat gun violence as a contagious disease, using trained "violence interrupters" from the community to mediate conflicts and change social norms around violence. These programs have shown reductions in shootings of 40-70% in target areas.

Trauma-informed schools create environments where students feel safe and supported rather than surveilled and punished. When schools address underlying trauma rather than simply disciplining disruptive behavior, both academic outcomes and violence rates improve.

Structural-Level Changes

Housing policy that promotes integration rather than segregation can break cycles of concentrated disadvantage. Economic development that creates pathways to legitimate employment provides alternatives to underground economies. Criminal justice reform that treats addiction and mental illness as health issues rather than crimes reduces incarceration's destabilizing effects on communities.

Comprehensive community development addresses multiple systems simultaneously—improving schools while creating jobs, enhancing public safety while strengthening social services, building housing while supporting small businesses.

A Systems-Level Solution: The Case for Universal Basic Income

Understanding violence through this root-cause lens reveals something profound: many of the drivers we've identified share a common thread, economic insecurity and its cascading effects. This insight points toward an intervention that could simultaneously address multiple levels of our "5 Whys" analysis: Universal Basic Income.

Consider what a UBI of $2,000 per month for adults and $500 per month for children would mean for the systemic conditions that foster violence:

Interrupting the Poverty-Violence Pipeline

At the most immediate level, UBI would dramatically reduce poverty, the foundation upon which so many other risk factors build. When families have their basic needs secured, the desperate choices that sometimes lead to violence become less necessary. The chronic stress of financial insecurity, which we know literally rewires developing brains toward hypervigilance and aggression, begins to ease.

But UBI's effects would ripple outward through the system. Parents with economic security can focus on nurturing their children rather than working multiple jobs just to survive. Communities with stable incomes can support local businesses, creating the economic foundation for stronger social bonds. Young people with guaranteed income have alternatives to underground economies that often involve violence.

Economic Cushioning and Opportunity Creation

UBI functions as what economists call an "automatic stabilizer", a policy that responds to economic downturns without requiring new legislation or bureaucratic processes. When a factory closes or a pandemic disrupts employment, communities with UBI maintain purchasing power, preventing the downward spiral that often accompanies economic shock.

More intriguingly, UBI could unlock entrepreneurship and creativity in communities that have been systematically disinvested from. When people aren't trapped in survival mode, they can take risks, starting businesses, pursuing education, engaging in community organizing. This economic dynamism creates the legitimate opportunities that serve as alternatives to violence-involved activities.

Breaking Intergenerational Cycles

Perhaps most powerfully, UBI addresses what social scientists call "intergenerational transmission of disadvantage". Children who grow up in families with economic security develop stronger cognitive skills, better emotional regulation, and greater educational achievement. They're less likely to experience the ACEs that increase violence risk, more likely to develop the social bonds that serve as protective factors.

Think of UBI as a form of "social soil"—the basic foundation that allows everything else to grow.

When the ground is fertile, investments in education, healthcare, and community development take root more easily. When it's depleted, even well-designed programs struggle to achieve lasting impact.

The Implementation Challenge: Fiscal Sustainability and Political Will

Of course, implementing UBI at this scale would require fundamental changes to how we structure our economy and allocate public resources. Fiscal sustainability represents the most immediate challenge, funding $2,000 monthly for roughly 260 million American adults would cost approximately $6.2 trillion annually, requiring creative approaches to revenue generation and program integration.

But innovative financing mechanisms exist. Progressive taxation on wealth and high incomes, carbon pricing that generates revenue while addressing climate change, financial transaction taxes that could moderate speculative trading, and consolidation of existing welfare programs could all contribute to funding streams.

More fundamentally, UBI would need to be understood not as an additional government expense, but as an investment in social infrastructure, like roads, schools, or the internet, that creates the conditions for broader economic growth and social stability.

Beyond Silver Bullets: UBI as Part of Comprehensive Strategy

UBI alone wouldn't solve gun violence, no single intervention could address such a complex, multi-layered problem. But it could serve as the foundation upon which other evidence-based interventions become more effective.

Trauma-informed schools work better when children aren't chronically stressed about housing insecurity. Community violence intervention programs have more success when young people have legitimate economic alternatives. Mental health services can focus on healing rather than crisis management when families have stable income.

UBI represents what systems theorists call a "leverage point", a place where small changes can produce significant improvements across an entire system. By addressing economic insecurity, it touches each level of our "5 Whys" analysis simultaneously.

The Path Forward: From Symptoms to Systems

This deeper understanding doesn't diminish the importance of immediate responses to violence, emergency medical care, crisis intervention, and public safety measures remain essential. But it suggests that sustainable solutions require sustained attention to root causes.

Just as public health campaigns eliminated smallpox and dramatically reduced smoking rates through comprehensive, long-term strategies, we can prevent violence by addressing its underlying drivers.

This means:

- Investing in children through quality early childhood education, trauma-informed healthcare, and family support services

- Strengthening communities through community development, resident leadership, and social cohesion programs

- Reforming systems that perpetuate inequality in education, criminal justice, housing, and economic opportunity

- Creating economic security through policies like UBI that provide a foundation for all other interventions

- Sustaining commitment beyond political cycles through dedicated institutions and protected funding streams

Conclusion: The Courage to Look Deeper

The next time gun violence captures national attention, we'll likely hear familiar debates about individual responsibility versus policy solutions, mental health versus gun access, security versus freedom. These conversations aren't meaningless, they address real aspects of a complex problem.

But if we're serious about creating safer communities, we must also have the courage to look deeper. We must ask why some communities struggle with chronic violence while others don't. We must examine the systems and structures that create these differences. We must commit to addressing root causes even when the work is harder, slower, and less politically convenient than focusing on symptoms alone.

The fever tells us something is wrong. But healing requires treating the infection, not just the temperature.

The tools for this deeper work exist. The research is clear. The question that remains is whether we have the collective will to move beyond surface-level solutions toward the systemic changes that can actually prevent violence before it occurs.

Because in the end, the most effective way to stop a shooting is to prevent the conditions that lead someone to pick up a gun in the first place.