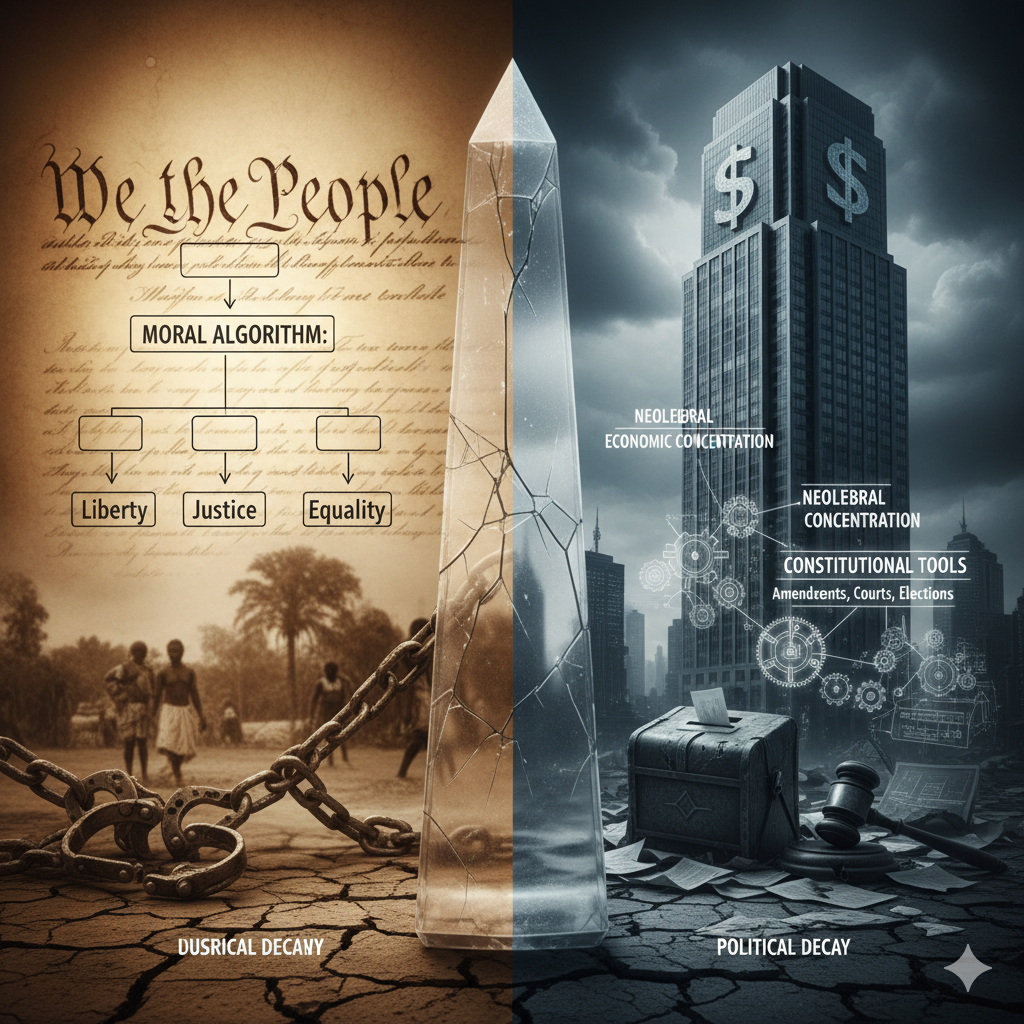

Dichotomy of the USA

The United States Constitution a founding document that encoded both profound inequality and the mechanism for recognizing and correcting that inequality.

A Directional Theory of Political Economy: Beyond Left and Right

Thesis

The conventional left-right political spectrum obscures more than it reveals. A more accurate framework maps political and economic systems along two intersecting axes: the concentration versus distribution of economic power, and the concentration versus distribution of political authority. When we evaluate ideologies not by their position on an artificial spectrum but by their directional momentum (what they move toward), we discover that democracy paradoxically trends toward anarchy through the dissolution of coherent authority, while neoliberalism accelerates toward authoritarianism through the consolidation of corporate power. Only a true republic, where impersonal law holds supremacy over both state tyranny and private oligarchy, can maintain the equilibrium necessary for human flourishing. This balance becomes the foundation upon which basic human needs can be universally met, enabling humanity's evolution toward higher forms of moral and social organization.

The Moral Algorithm: America's Founding Principle

John Adams articulated what might be called America's foundational equation, its "Moral Algorithm," in words that remain radical even today:

"Government is instituted for the common good; for the protection, safety, prosperity, and happiness of the people; and not for the profit, honor, or private interest of any one man, family, or class of men and to reform, alter, or totally change the same, when their protection, safety, prosperity and happiness require it."

This is not merely lofty rhetoric but a diagnostic instrument: a measuring tool for determining whether any political or economic system is moving toward or away from legitimate governance. Adams provides us with a clear criterion: Does the system serve the common good, or does it serve concentrated private interests? And crucially, when it fails this test, it must be reformed or abolished.

The American Revolution itself was a directional judgment made manifest. The Boston Tea Party, mythologized as a simple tax protest, was in fact a rejection of corporate capture of government. The British Crown had granted the East India Trading Company monopolistic privileges and favorable treatment that benefited corporate shareholders at the expense of colonial merchants and citizens. The revolutionaries weren't merely objecting to taxation without representation; they were rebelling against a system where government had been corrupted to serve "the profit, honor, or private interest" of a corporate class rather than the common good.

This historical moment reveals something crucial: the American founding wasn't about choosing between capitalism and socialism, or between democracy and authoritarianism. It was about rejecting any system (regardless of its ideological label) that concentrated power in ways that betrayed the common welfare. The Moral Algorithm provides the metric: measure every system, every policy, every institutional arrangement by whether it moves toward serving collective flourishing or toward serving concentrated interests.

The Economic Axis: Concentration and Distribution of Power

Capitalism and socialism represent opposing gravitational forces acting upon economic power. Capitalism, in its pure form, generates centripetal momentum, drawing wealth, resources, and decision-making authority toward ever-smaller concentrations of private hands. Market competition, despite its theoretical promise of distributed opportunity, produces winners who accumulate advantages that compound over time. Capital begets capital; market dominance enables the purchase of favorable regulation; economic power converts seamlessly into political influence.

Socialism exerts the opposite force, distributing economic decision-making across broader populations through collective ownership and democratic planning. Where capitalism concentrates, socialism diffuses. Yet both systems exist on the same highway. They are not opposites in kind but in direction. Both grapple with the fundamental question of who decides how resources are allocated, produced, and distributed. The difference lies in whether that power flows inward toward concentrated nodes or outward toward distributed networks.

Adams's Moral Algorithm cuts through ideological abstractions to ask the essential question: In whose interest does the economic system operate? When capitalism concentrates wealth and power such that government becomes the instrument of private interests (as it had under British corporate monopolies), it violates the founding principle regardless of its market efficiencies. When socialism creates a new class of party elites who exploit state power for private benefit, it equally betrays the common good regardless of its egalitarian rhetoric.

The critical error in traditional analysis is treating these as binary choices or moral absolutes. Instead, we must ask: in which direction is the system currently moving? Is economic power consolidating or dispersing? And most importantly: is it moving toward or away from serving the common good? A nominally capitalist society with robust antitrust enforcement, progressive taxation, and worker protections may be moving toward the common welfare, while a nominally socialist society with corrupt party elites controlling state enterprises may be moving toward private enrichment.

The Political Axis: From Anarchy to Authoritarianism

The political axis maps the structure of authority itself. At one extreme lies anarchy: the absence of centralized coercive power, where no individual or institution claims the right to rule over others. At the opposite extreme stands authoritarianism: the concentration of political power in a single entity, whether an individual, party, or apparatus that monopolizes the legitimate use of force.

This axis is independent of the economic one, though they interact in complex ways. You can have authoritarian capitalism (fascism, corporatism) or authoritarian socialism (Stalinism, state communism). You can theorize anarchist capitalism (anarcho-capitalism) or anarchist socialism (anarcho-communism, syndicalism). The combinations reveal that economic organization and political authority are separate variables that can be mixed in different proportions.

The republic occupies the crucial center point on this axis. In a true republic, neither individuals nor factions nor economic interests hold ultimate authority. Instead, law itself (impersonal, procedural, and constitutionally constrained) becomes the sovereign. This is Adams's vision operationalized: government as an institution dedicated to the common good, structured so that no "one man, family, or class of men" can capture it for private purposes.

Democracy's Anarchic Tendency

Here lies a profound paradox that few political theorists adequately address: democracy, when unbounded by constitutional restraint, drifts toward anarchy through the fragmentation and delegitimization of authority itself.

Pure democracy operates on the principle of majority rule in all matters. As this principle extends into every domain of governance, several destabilizing dynamics emerge. First, the constant contestation of every decision through majoritarian mechanisms creates radical uncertainty about the stability of law. What one majority establishes, the next may dissolve. No principle stands above the current majority's preferences.

Second, democracy without constitutional limits reduces politics to pure power calculation. Minority rights, procedural protections, and individual liberties become negotiable based on current majorities. This breeds a corrosive form of cynicism: why respect laws that are merely crystallized expressions of current power rather than binding principles?

Third, as democratic participation intensifies and extends to more domains, authority becomes so diffuse that coherent governance becomes impossible. Every decision requires consensus-building among atomized individuals who recognize no authority beyond their own consent. This is not freedom but paralysis: the inability to make collective decisions that bind us over time.

When measured against Adams's Moral Algorithm, unconstrained democracy fails because it cannot reliably secure "the protection, safety, prosperity, and happiness of the people." Governance requires the capacity to act coherently over time, to make binding commitments, to enforce laws that constrain immediate desires for long-term benefit. Anarchy (the endpoint of democracy's directional movement) cannot provide these goods.

The anarchic tendency of unconstrained democracy explains why ancient republics feared it and why the American founders deliberately created a republic rather than a democracy. They understood that democracy, as a directional force, moves away from concentrated authority (which seems desirable) but potentially all the way to the absence of coherent authority, which is incompatible with the common good.

Neoliberalism's Authoritarian Trajectory: The Return of Corporate Rule

If democracy drifts toward anarchy, neoliberalism accelerates toward authoritarianism through the privatization of sovereignty itself: a betrayal of the American Revolution's core principle that uncannily mirrors the very system the founders rejected.

Neoliberalism is not simply "free market capitalism." It is a specific ideological project that seeks to reorganize all of society according to market logic, reducing government functions to the enforcement of contracts and property rights while expanding market mechanisms into every domain of human life: education, healthcare, public safety, even governance itself.

The parallel to British colonial rule is striking. Just as the East India Trading Company received government protection and favorable treatment that allowed it to dominate colonial commerce, contemporary neoliberalism creates regulatory frameworks that privilege corporate interests over the common good. Tax structures that benefit capital over labor, trade agreements that protect investor rights over worker rights, deregulation that removes constraints on corporate behavior: these represent the modern equivalent of Crown-granted monopolies.

The authoritarian momentum emerges from several mechanisms. First, neoliberalism generates massive economic inequality by design, concentrating wealth among those who already possess capital while stripping away the social protections that allowed workers to bargain collectively for better conditions. This economic concentration directly converts into political power through lobbying, campaign finance, media ownership, and the revolving door between corporate leadership and regulatory positions.

This is precisely what Adams warned against: government captured for "the profit, honor, or private interest" of a class rather than "the common good." When pharmaceutical companies write drug regulations, when financial institutions author financial rules, when tech monopolies shape privacy law, we have recreated the exact system of corporate governance that sparked revolution.

Second, neoliberalism achieves what might be called "authoritarian privatization." Functions traditionally performed by democratically accountable governments (from prisons to schools to military operations) are transferred to private corporations accountable only to shareholders. This creates authoritarian power structures (corporate hierarchies are definitionally authoritarian) that are insulated from democratic oversight. You cannot vote out a CEO, and corporate decisions are made through top-down authority, not deliberative consensus.

Third, when neoliberal policies produce social breakdown (rising inequality, precarious employment, collapsing public services), the response is increased surveillance, policing, and incarceration. The state withdraws from social provision but expands its coercive apparatus. This produces the characteristic neoliberal form: a weak social state combined with a strong punitive state. Government abandons its role in ensuring "the protection, safety, prosperity, and happiness of the people" while strengthening its capacity to protect property and enforce contracts that benefit concentrated wealth.

Finally, neoliberalism's claim that "there is no alternative" to market organization is itself authoritarian in character. It places economic arrangements beyond democratic deliberation by declaring them natural and inevitable. This is the soft authoritarianism of technocratic necessity, where experts and markets make the "hard choices" that politics supposedly cannot handle: precisely the kind of rule by unaccountable elites that republics were designed to prevent.

The endpoint toward which neoliberalism trends is not classical fascism but something more subtle: a corporate authoritarianism where formal democratic institutions persist as hollow shells while real power resides in concentrations of private capital that face no meaningful accountability. We vote for politicians who govern an increasingly narrow domain while unelected corporate leadership makes the decisions that actually structure our lives. This is the East India Trading Company model perfected: corporate power exercising governmental authority without the inconvenience of even nominal Crown oversight.

Directional Analysis: The Moral Algorithm as Compass

Evaluating ideologies by their directional movement rather than their left-right position is methodologically crucial. Adams's principle provides the compass: we measure every system by whether it is moving toward or away from serving the common good.

Consider how this transforms our understanding. Traditional left-right analysis categorizes nations by ideological labels that reveal little about their actual trajectory. Directional analysis, measured against the Moral Algorithm, exposes the truth behind the propaganda.

Norway: Equilibrium in Motion

Norway demonstrates what movement toward the common good looks like in practice. Economically, it has maintained distributed prosperity through strong labor unions, progressive taxation, and sovereign wealth management that prevents resource extraction from benefiting only elites. The state owns significant portions of key industries (including 67% of Equinor, the oil company), yet markets function efficiently and entrepreneurship thrives.

Politically, Norway maintains robust republican institutions with strong constitutional protections, an independent judiciary, and low corruption. Power is distributed through proportional representation and active civic participation. Most critically, the system demonstrably serves the common welfare: universal healthcare, free education through university, strong social safety nets, and high economic mobility. By every measure Adams specified (protection, safety, prosperity, happiness), Norway succeeds.

Direction of travel: Norway is moving toward equilibrium, actively correcting when economic concentration threatens to undermine political equality. It neither fragments toward anarchic dysfunction nor consolidates toward authoritarian control. It serves as proof that the Moral Algorithm can be operationalized.

China: Authoritarian Consolidation with Elite Capture

China's trajectory reveals how socialist rhetoric can mask movement toward concentrated power serving class interests. Economically, China has created a system where state-connected corporations and party elites control vast wealth. The "socialist market economy" operates primarily for the enrichment of those with political connections. Income inequality in China now exceeds that of the United States, and wealth concentration rivals any capitalist nation.

Politically, China is accelerating toward extreme authoritarianism. The Communist Party monopolizes all political power, Xi Jinping has eliminated term limits, surveillance systems track citizens' every movement, and dissent is crushed systematically. This is not government "for the protection, safety, prosperity, and happiness of the people" but government for the maintenance of party power and elite privilege.

The system flagrantly violates the Moral Algorithm on both axes. It concentrates both economic and political power, and serves the interests of party elites rather than the common good. Workers have no independent unions, citizens have no political voice, and the state exists to perpetuate the rule of "one man, family, or class of men."

Direction of travel: China is accelerating toward authoritarian capitalism (despite its socialist branding), with both economic and political power consolidating in party-connected elites. This is movement away from the common good toward class dominance.

Cuba: Stagnation in Authoritarian Scarcity

Cuba presents a case of authoritarian socialism that has ossified into a system serving neither the common good nor successful development. Economically, central planning has produced chronic scarcity, with the population lacking basic goods while party elites access special stores and privileges. The system distributes poverty rather than prosperity, failing the "prosperity" criterion entirely.

Politically, Cuba maintains one-party authoritarian control, with the Communist Party constitutionally defined as the "superior leading force" of society. There is no meaningful political participation, no freedom of speech or press, and dissent is criminalized. Citizens cannot "reform, alter, or totally change" their government as Adams insisted is their right.

Cuba does provide universal (if under-resourced) healthcare and education, demonstrating that authoritarian systems can sometimes address basic needs. However, the lack of political freedom, economic opportunity, and capacity for self-governance represents a fundamental failure of the Moral Algorithm. Protection and safety exist primarily for the party; prosperity is absent; happiness is constrained by political repression.

Direction of travel: Cuba is stagnant in authoritarian consolidation. It moved there decades ago and remains frozen, maintaining political authoritarianism while its economic system slowly collapses. It serves the interest of party continuity rather than popular welfare.

Venezuela: Collapse Through Elite Predation

Venezuela demonstrates how rapid movement toward concentrated power can destroy a nation's capacity to serve the common good. Under Chávez and Maduro, what began as populist resource redistribution devolved into kleptocratic authoritarianism.

Economically, Venezuela exemplifies elite capture disguised as socialism. State control of the oil industry and other sectors created opportunities for massive corruption. Party-connected elites siphon billions while the population faces hyperinflation, starvation, and medical supply shortages. This is government explicitly for "the profit, honor, or private interest" of the ruling class.

Politically, Venezuela has accelerated toward authoritarianism: rigged elections, political prisoners, suppression of opposition, military control of dissent, and the dissolution of constitutional constraints. The government serves to maintain regime power, not to provide "protection, safety, prosperity, and happiness."

The result is catastrophic by every measure: economic collapse, mass emigration, humanitarian crisis. Venezuela violates the Moral Algorithm absolutely, with concentrated power serving concentrated interests while the population suffers.

Direction of travel: Venezuela is in rapid authoritarian acceleration with complete elite capture. It moved from democratic capitalism toward what it claimed would be socialism for the people but has arrived at authoritarian kleptocracy serving a predatory ruling class.

Russia: Authoritarian Oligarchy

Russia's post-Soviet trajectory moved from the chaotic fragmentation of the 1990s toward consolidated authoritarian capitalism under Putin. Economically, the state and oligarchs closely tied to the Kremlin control key industries (energy, minerals, banking). Wealth is concentrated among a small elite while the broader population has seen modest gains that can be revoked by political decisions.

Politically, Russia has steadily moved toward authoritarianism: elimination of meaningful opposition, state control of media, constitutional amendments enabling indefinite Putin rule, crushing of civil society, and political assassinations. Elections are performative rather than competitive. Citizens cannot meaningfully participate in self-governance or reform their government.

The system serves the interests of Putin and the oligarchic class connected to him. It provides a degree of stability and modest prosperity compared to the 1990s chaos, but this comes at the cost of political freedom, accountability, and the rule of law. It is explicitly government for the benefit of "one man, family, or class of men" rather than the common good.

Direction of travel: Russia is moving steadily toward authoritarian oligarchy, with both economic and political power consolidating around the Kremlin and connected elites. This is movement away from republican principles toward concentrated power serving private interests.

United States: The Paradox of Aspiration and Betrayal

The United States presents the most complex case because its founding documents encoded the Moral Algorithm while simultaneously violating it through the creation of what might be called a "Club of Whiteness": a structure of inherent inequality that excluded women, enslaved people, and indigenous populations from the common good it claimed to serve.

The Constitution established a goal: a republic where law rules, where government serves the common good, where every person can meet their needs, develop their capacities, and participate as equals in collective self-governance. This was never the reality; it was the aspiration. The founding documents created both the tool (the Moral Algorithm) and the mechanism (constitutional amendment and reform) by which descendants could recognize and address these fundamental flaws.

The historical trajectory shows this tension. The Civil War and Reconstruction, the women's suffrage movement, the labor movement, the Civil Rights Movement, and ongoing struggles for equality represent successive attempts to move the nation toward the aspirational republic rather than the exclusionary reality. Each represented recognition that the system was serving "the profit, honor, or private interest" of some rather than the common good of all.

Current Direction of Travel: The contemporary United States is moving away from its republican aspirations on both axes. Economically, it has embraced neoliberalism aggressively since the 1980s. Wealth concentration now rivals the Gilded Age. The top 1% owns more wealth than the entire middle class. Corporate power writes legislation, funds campaigns, and captures regulatory agencies. This is the East India Trading Company model revived: government serving concentrated economic interests rather than the common good.

Tax policy, trade agreements, labor law, healthcare systems, and education funding all reflect movement toward serving corporate and elite interests rather than ensuring "the protection, safety, prosperity, and happiness of the people." Real wages have stagnated for decades while productivity and profits soared. Economic insecurity has become the norm for the majority while billionaire wealth exploded.

Politically, the U.S. shows troubling movement toward both fragmentation and authoritarianism simultaneously. Democratic norms are eroding, political polarization prevents coherent governance, and constitutional crises multiply. At the same time, executive power expands, surveillance intensifies, money dominates politics, and access to voting becomes contested terrain.

The system increasingly violates the Moral Algorithm. It does not serve the common good but rather concentrated interests: pharmaceutical companies profiting from healthcare scarcity, financial institutions extracting wealth through debt, tech monopolies commodifying human attention, and fossil fuel companies blocking climate action. When the government does act, it often serves these interests rather than the population.

Yet the Moral Algorithm itself provides the diagnostic tool. The Constitution's mechanisms for reform, the tradition of mass movements forcing change, and the explicit standard Adams articulated all remain available. The recognition that the system has failed its purpose is the first step toward the reform, alteration, or total change that Adams insisted was not merely permitted but required.

Direction of travel: The United States is moving away from its republican aspirations on both axes. Economically, it accelerates toward neoliberal concentration of wealth and corporate capture of government. Politically, it shows signs of both democratic fragmentation and authoritarian consolidation, with institutions designed for the common good increasingly serving private interests. The critical question is whether the directional momentum can be reversed using the tools the founders provided.

The Republic as Equilibrium

The republic, properly conceived, occupies the stable center between anarchy and authoritarianism, between concentrated and distributed power. Most importantly, it is the institutional embodiment of the Moral Algorithm: the form of government designed explicitly to prevent capture by private interests while ensuring the common welfare.

It achieves this through several mechanisms. First, constitutional law places limits on all actors: majorities, minorities, governments, and private powers. No faction can claim absolute authority because all are subordinate to fundamental law. This prevents both the tyranny of the majority (democracy's anarchic dissolution of stable authority) and the tyranny of concentrated power (authoritarianism), whether that concentration occurs in the state or in private hands.

Second, republican institutions create balanced tension between distributed and concentrated decision-making. Federalism distributes power geographically. Separation of powers distributes it functionally. Bicameral legislatures require multiple forms of representation to concur. These structures prevent both the paralysis of total fragmentation and the danger of total concentration, while making it difficult for any single interest (including corporate interests) to capture all levers of power simultaneously.

Third, the republic protects a sphere of individual rights that remain beyond legitimate government power regardless of majority will or state necessity. This includes both classical liberal rights (speech, assembly, property) and what we might call social rights (the material prerequisites for autonomous existence). These rights protect individuals from both state tyranny and private power: a crucial addition that addresses the lesson of the Boston Tea Party. Threats to liberty come not only from governments but from concentrated economic interests.

Fourth, and crucially, the republic uses law to regulate economic power, preventing its concentration from undermining political equality. This is not a deviation from republican principles but essential to their maintenance. The founders understood this: they broke up loyalist estates, prohibited primogeniture, and designed a system that was meant to prevent the emergence of an aristocracy, whether titled or moneyed.

Antitrust law, progressive taxation, labor rights, and social provision are modern expressions of the same principle: when economic inequality becomes too extreme, wealthy interests capture political institutions and the republic collapses into oligarchy, a form of soft authoritarianism where government exists for "the profit, honor, or private interest" of a class rather than the common good. The republic must actively prevent this concentration to remain a republic.

The republic's stability depends on active maintenance of this equilibrium. It is not a static achievement but a dynamic balancing act, requiring constant adjustment as new concentrations of power emerge and new threats to rights appear. The republic moves neither toward anarchy nor toward authoritarianism, but holds the center through institutional design and civic commitment, always measured against Adams's standard: does it serve the common good?

Norway demonstrates this balance in action. The United States encoded it as aspiration while violating it in practice. China and Russia show what happens when the pretense of serving the common good masks authoritarian consolidation. Cuba and Venezuela reveal how authoritarian systems, whether frozen or collapsing, cannot deliver on the Moral Algorithm's requirements.

Basic Needs as Precondition for Development

The final element of this framework addresses the purpose of achieving this political-economic equilibrium: to enable human development beyond mere survival. This connects directly to Adams's formulation. Government exists for "the protection, safety, prosperity, and happiness of the people." These are not abstractions but concrete material conditions.

Protection requires security of person and property. Safety requires not merely police but stable social conditions free from desperation. Prosperity means access to the resources necessary for a dignified life. Happiness (in the eighteenth-century sense) means the opportunity to pursue one's conception of the good life, which requires freedom from grinding necessity.

Maslow's hierarchy offers one articulation of this insight: physiological needs must be met before safety concerns can be addressed; safety must be secured before love and belonging become primary; only when these are satisfied can self-actualization emerge. Extended to social analysis, this suggests that a society where many struggle for basic survival cannot develop higher forms of moral and social organization.

When people lack secure access to food, shelter, healthcare, and education, their time and energy necessarily focus on immediate survival. They cannot meaningfully participate in deliberative democracy, engage in creative work, develop their capacities, or contribute to cultural advancement. This is not a moral failing but a material constraint. A republic that fails to ensure these prerequisites has failed the Moral Algorithm: it is not serving "the protection, safety, prosperity, and happiness of the people."

Moreover, extreme material insecurity breeds social pathologies. Competition for scarce resources intensifies group conflict. Fear of deprivation makes people susceptible to authoritarian promises of security. Lack of education prevents critical engagement with propaganda. Economic desperation makes exploitation possible. None of the higher human capacities (compassion, creativity, wisdom, cooperation) can flourish in a context of generalized scarcity and insecurity.

Therefore, the republic's legitimacy depends not merely on procedural correctness but on substantive outcomes. A political system that protects formal rights while allowing mass deprivation is not a true republic but an oligarchy with republican aesthetics: government for the profit of a class rather than the common good. The equilibrium between anarchy and authoritarianism, between concentrated and distributed power, must be calibrated to ensure that every person has access to the material prerequisites for autonomous existence.

This is not utopianism but developmental logic, and it is the explicit purpose Adams articulated. Meeting basic needs universally is not the endpoint of human development but the precondition for beginning it. A government that fails this test has lost its legitimacy and must, as Adams wrote, be reformed, altered, or totally changed.

Norway achieves this, demonstrating that prosperity and security can be universally distributed while maintaining both economic vitality and political freedom. The United States fails this test increasingly, with millions lacking healthcare, housing security, and educational opportunity despite vast national wealth. China provides some basic security while denying political freedom, a partial fulfillment that cannot satisfy the full requirements. Cuba distributes scarcity while preventing self-governance. Venezuela has collapsed into humanitarian crisis. Russia provides modest stability for some while concentrating wealth and crushing dissent.

The pattern is clear: systems that move toward the common good must provide both material security and political freedom. Neither alone suffices. Prosperity without liberty is gilded captivity. Liberty without prosperity is freedom to starve. The Moral Algorithm demands both.

The Constitutional Paradox: The Tool for Its Own Correction

The United States Constitution represents a unique historical moment: a founding document that encoded both profound inequality and the mechanism for recognizing and correcting that inequality. This paradox deserves examination because it illuminates how systems can contain the seeds of their own reform.

The Constitution established the aspiration of republican government serving the common good while simultaneously creating a "Club of Whiteness" that excluded the majority of humans within its borders from that common good. Enslaved people were property, not persons. Women could not vote, own property independently, or participate in governance. Indigenous peoples were not citizens. Poor white men without property were often excluded. The system was designed by and for a narrow class.

Yet the Constitution also established several crucial elements:

First, it encoded the principle that government legitimacy derives from serving the people, not from divine right, tradition, or force. This principle, once established, could be interrogated: which people? Why these and not others?

Second, it created amendment procedures, establishing that the Constitution itself could be reformed when it failed to serve its purposes. This mechanism acknowledged imperfection and provided the path to correction.

Third, it established rights and principles in universal language ("all men are created equal," "we the people") even while denying those rights to most people. This created a contradiction that generations could exploit. Frederick Douglass famously argued that the Constitution was anti-slavery in its principles even if not in its application, and that the task was to make practice match principle.

Fourth, and most importantly for this analysis, it established the Moral Algorithm as the standard by which government could be judged. Adams's formulation became the measuring stick that could be used to indict the system itself. If government exists for the common good and not for the benefit of a class, then slavery violated the founding principle. If government exists for prosperity and happiness, then denying half the population political participation violated the founding principle.

The abolitionist movement, the women's suffrage movement, the labor movement, the Civil Rights Movement: each deployed the Moral Algorithm against the system that had betrayed it. "We hold these truths to be self-evident" became the weapon used to dismantle the exclusions the founders had built. The tool contained the means of its own correction.

This pattern continues. When contemporary activists point out that the system serves corporate interests rather than the common good, they invoke the Moral Algorithm. When they demonstrate that millions lack basic security in the wealthiest nation in history, they measure current reality against the constitutional aspiration. When they show that political power has been captured by concentrated wealth, they use the founders' own principles to indict contemporary betrayal.

The Constitution's goal was a republic where law rules, where government serves the common good, where every person can meet their needs, develop their capacities, and participate as equals in collective self-governance. This was never the reality. It was always the aspiration, the direction of travel the system claimed to pursue even while violating it.

The genius and the tragedy of the American founding is that it created both the problem and the solution. It established systematic inequality while providing the principle by which that inequality could be recognized as illegitimate. It concentrated power in a narrow class while articulating the standard that such concentration violated legitimate governance.

Descendants can recognize these flaws precisely because the Moral Algorithm was embedded in the founding. The system provided the tool for diagnosing its own failures. When it serves "the profit, honor, or private interest of any one man, family, or class of men" rather than the common good, we know it has failed not by external standards but by its own stated purpose.

This is why directional analysis matters so profoundly. The question is never whether any system has achieved perfection. The question is always whether it is moving toward or away from the common good. The United States Constitution established the destination while creating massive obstacles to reaching it. The journey has been long, bloody, and incomplete. But the compass remains: does the system serve the common good, or does it serve concentrated interests?

When the answer is the latter, Adams is explicit: we have not merely the right but the duty to reform, alter, or totally change it. The Constitution itself contains this revolutionary principle. It is, perhaps, the only founding document in history that explicitly authorizes its own overthrow should it fail its purpose.

Conclusion: The Path Forward

This framework suggests a radical reorientation of political analysis and action. Instead of asking whether we should move "left" or "right," we should ask: In which direction are we currently moving, and in which direction should we move? Adams provides the ultimate criterion: Are we moving toward or away from the common good?

The examples of nations analyzed reveal clear patterns:

Movement toward the common good requires balanced distribution of both economic and political power, measured by concrete outcomes (prosperity, security, freedom) rather than ideological labels. Norway demonstrates this is achievable.

Movement away from the common good manifests as concentration of power serving elite interests regardless of whether the system calls itself capitalist or socialist, democratic or revolutionary. China, Russia, Venezuela, and Cuba demonstrate various forms of this betrayal.

The United States occupies a tragic position: its founding documents encode the Moral Algorithm while its founding practice violated it systematically. Its current trajectory moves away from its republican aspirations through neoliberal economic concentration and political decay, yet the tools for correction remain embedded in the constitutional structure.

The directional questions become concrete:

Are we drifting toward the paralysis of anarchy, where no authority can act coherently for collective welfare? Then we need stronger republican institutions, not more democracy.

Are we accelerating toward authoritarianism, whether through state concentration or corporate domination? Then we need constitutional limits, distributed power, and protected rights, not technocratic management or market fundamentalism. The Boston Tea Party was not a rejection of all government but a rejection of government captured by private interests. We need government strong enough to serve the common good and constrained enough that it cannot be captured for private profit.

Is economic power concentrating in ways that undermine political equality, creating a new East India Trading Company model where corporations write the rules that govern them? Then we need policies that distribute economic resources and opportunities, not because equality itself is the goal, but because concentrated economic power inevitably becomes concentrated political power that serves class interests rather than the common welfare.

Are people's basic needs going unmet in ways that prevent their full development and violate the purposes Adams articulated? Then meeting those needs is not charity but the foundation of a legitimate social order: the minimum requirement for government to fulfill its purpose of ensuring "the protection, safety, prosperity, and happiness of the people."

The republic, understood as the system where law rules and power is balanced, becomes not a static form but a perpetual project. It requires constant vigilance against both directions of failure: the dissolution of coherent authority and the concentration of tyrannical power. It demands that we attend not to the ideological labels people claim but to the actual directional movement their policies produce.

Most fundamentally, it insists that political and economic arrangements be judged by the Moral Algorithm Adams articulated: Does the system serve the common good, or does it serve concentrated private interests? When it fails this test (when government exists for "the profit, honor, or private interest of any one man, family, or class of men"), we have not merely the right but the duty to reform, alter, or totally change it.

The highway has two lanes, but it leads somewhere. The American Revolution established the destination: a society organized for the common good, where every person can meet their needs, develop their capacities, and participate as equals in collective self-governance. This is the true test of any system: not its ideological purity but its directional movement toward or away from the conditions that allow humanity to realize its potential.

We know what we're moving away from. We fought a revolution against it. The question is whether we have the clarity to recognize when we're moving back toward it (regardless of the ideological disguises it wears) and the courage to change course when the common good demands it. The Moral Algorithm provides the measurement. Directional analysis provides the method. The constitutional mechanism provides the tool. What remains is the will to use them.