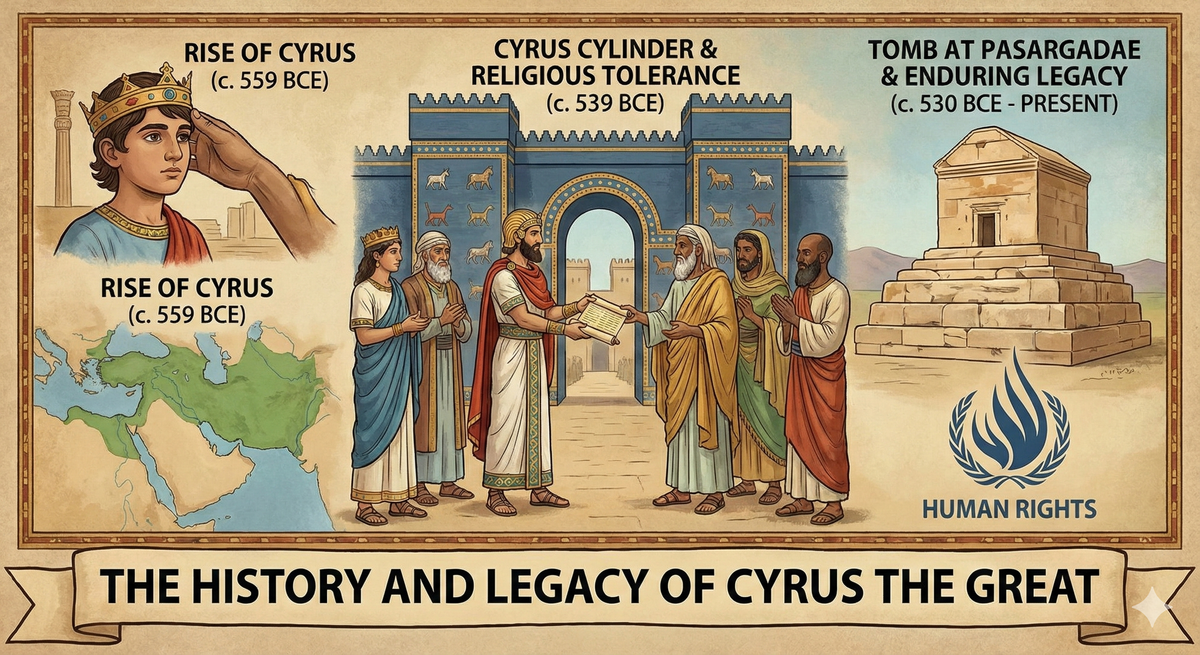

Cyrus the Great

Founder of the Persian Empire, Cyrus the Great is famed for unprecedented tolerance. Upon taking Babylon, he freed slaves and permitted religious diversity rather than imposing his will. His enlightened decrees, recorded on the Cyrus Cylinder, are celebrated as an ancient foundation of human rights.

Cyrus the Great: The Father of Human Rights and the Revolutionary Vision of Empire

Introduction: A Leader Who Changed the Rules

In 539 BC, a Persian king entered the city of Babylon without a battle. His army had cleverly redirected the Tigris River, lowering the water level enough to march through the gap in the walls where the river flowed. The city surrendered. This conquest alone would have made him remarkable. But what happened next changed the course of human history.

This king, Cyrus II of Persia, known to history as Cyrus the Great, did something no conqueror before him had ever done. He told the conquered people they were now partners, not subjects. He freed captives. He rebuilt temples. He declared that all people in his empire had rights that even he, as absolute monarch, could not violate.

This is the story of how one leader created the world's first bill of rights, governed 44% of humanity with unprecedented tolerance, and established principles that still inspire us 2,500 years later. But to understand Cyrus, we must first understand the world that shaped him.

The Ancient Landscape: Aryans, Horses, and the Foundation of Iranian Civilization

The Revolutionary Power of the Horse

Approximately 4,000 years before Cyrus, a people called the Aryans lived in the steppes of Central Asia, probably in what is now Kazakhstan. Archaeological evidence suggests this origin because fire temples form a line from Kazakhstan southward to Iran, with the temples growing progressively younger as you move south. This pattern indicates a migration route.

The Aryans made a discovery that transformed human warfare forever. Horses had been domesticated before, but mainly as food. The Aryans realized something extraordinary: if you jumped on a horse's back, grabbed a fistful of mane to hold on, and squeezed hard with your leg muscles, you could charge at another person while swinging a weapon at their head.

This created an overwhelming advantage. The mounted warrior struck downward at the enemy's head while the enemy could only reach upward to strike the rider's legs. If outnumbered, the mounted warrior simply rode away, too fast to chase on foot. If the enemy tried to flee, the mounted warrior pursued and struck them from behind.

This innovation, combined with the bow and arrow and the spear, represented one of humanity's three greatest weapons technologies. Armed with this military superiority, the Aryans conquered the Iranian plateau and named it after themselves. Iran literally means "land of the Aryans," just as Ireland (Erin in its native language) also derives from the same root.

The Great Dispersal and Cultural Legacy

The Aryans then divided into three major groups, each shaping different regions of the ancient world:

The Indian Branch conquered approximately 70% of the Indian subcontinent, bringing their languages, culture, and social systems to merge with existing populations.

The Iranian Branch remained on the Iranian plateau, becoming the ancestors of the Pashtun, Tajiks, Dari, Baluchi, Sistanis, Kurds, and Persians. These groups would form the cultural foundation of the Persian Empire.

The European Branch followed an unexpected path to conquest. Rather than traveling through Russia and Ukraine, the Celts moved south through Iraq, where they discovered the bagpipe (invented in Iraq, not Scotland). They continued through Palestine and Egypt, crossing all of North Africa. Traditional bagpipe music still exists in Tunisia today as evidence of their passage. They left the bagpipe behind there, crossed the Straits of Gibraltar, and then transformed from migrants into conquerors.

The Celts swept across Europe from Spain to Britain, through Germany and Poland into the Balkans, eventually looping back to conquer central Turkey. The names remain as evidence: Galatia (central Turkey), Galicia (northwestern Spain), Gaul (France), and Galicia (southern Poland) all mean "land of the Celts."

Subsequent waves of Aryans (Romans, Greeks, Albanians, Slavs) followed, ultimately overwhelming the native European population. Only one group successfully resisted for 4,000 years: the Basque people of northern Spain and southwestern France. While politically conquered by Spain and France, they were never ethnically or culturally assimilated or destroyed.

Why Conquered Peoples Look Like Locals

An important principle of genetics explains why Aryan descendants appear so different across regions. When a minority conquering population breeds with a majority local population over 3,000 years, the minority's DNA becomes absorbed by the majority.

This is why Indians with Aryan ancestry look Indian, Europeans with Aryan ancestry look like native Europeans, and modern Turks look Middle Eastern rather than Central Asian (as their ancestors appeared a thousand years ago). The conquerors' genes merged with local populations, creating the physical diversity we see today while maintaining linguistic and cultural continuities.

The Cultural Spectrum of Iranian Peoples

The Iranians who remained on the plateau developed a remarkable range of cultures from north to south, from wild to refined.

The Northern Scythians: Warriors of the Steppes

In the north, stretching from Kazakhstan across southern Russia into Ukraine and modern Romania, lived the Scythians (called Saka in Persian). These were the "uncivilized" Iranians who embodied steppe warrior culture in its most extreme form.

Scythian warriors drank wine mixed with ephedra (a powerful stimulant) from cups made of human skulls. They covered themselves in tattoos and created decorative scars with knives. They were formidable horseback archers, and both men and women fought as warriors.

The Historical Reality of Amazons: The Greek myth of Amazon warriors has a factual basis in Scythian culture. The Scythians maintained all-woman archer divisions famous for their skill. When the Armenians (who also had female archer units) hired a Scythian women's division, something went catastrophically wrong after several years. The Scythian women "snapped" and marched west through northern Turkey to the Aegean coast, then turned south and systematically attacked Greek colonies one after another.

Archaeological evidence confirms this event. Beneath temples in the region lie the burned ruins of older temples destroyed during this rampage. The Scythian women sacked cities from Ephesus to Caria before suddenly stopping and departing. This traumatic event became the Greek Amazon mythology, a cautionary tale that parents used to frighten children into obedience.

The Scythians also invented polo, though their version bore little resemblance to the modern game. Every horseman played for himself, no teams existed, and players could choose whether to strike a sheep's head (tied in skin) toward a pole or simply strike other horsemen with their bats. It was full-contact warfare disguised as sport.

When Russians killed Afghan sheep during their war in Afghanistan, the Afghans found substitute heads and continued playing. The Scythians would not be stopped from their favorite pastime.

The Southern Persians: Refinement and Civilization

Further south, Iranian culture became progressively more "civilized." The Medes ate with their hands, talked during meals, and burped while eating. This offended their southern cousins, the Persians, who considered such behavior barbaric.

The Persians ate with utensils, maintained complete silence while eating, and never released gas from their bodies in public. They viewed themselves as the pinnacle of civilization and questioned why their Median cousins behaved so crudely. This cultural gradient created tension but also demonstrated the diversity within the Iranian peoples.

The Median language is now extinct, but it was very similar to Kurdish and Persian. Speakers of these languages would likely have understood Median, suggesting strong linguistic connections despite cultural differences in etiquette and custom.

The Rise of Empires and the Invention of Money

The Assyrian Dominance and Its Collapse

The western portion of the Iranian plateau fell under the brutal control of the Assyrian Empire, which dominated territory from Egypt to western Iran. The Assyrians were renowned for spectacular artwork and military prowess, but they ruled conquered peoples harshly. Losing to the Assyrians meant suffering.

However, by approximately 685 BC, the Assyrian Empire entered its death throes. Persian and Median resistance gradually carved out independence. The Median state grew powerful enough to become a regional force, and the Persians became a satellite state under Median control.

The Assyrian Empire collapsed around 620 BC, replaced by the Neo-Babylonian Empire, which conquered all of Mesopotamia, Syria, and Palestine. The Babylonians particularly resented Jewish resistance in Palestine. They destroyed Solomon's Temple and forced a large portion of the Jewish population to live in Babylon. These Jews were not slaves (though some Jewish slaves certainly existed in Babylon), but captives. They lived as free people but could not leave Babylon. This system resembled what Europeans would later call serfdom: urban confinement rather than agricultural bondage.

The Revolutionary Invention of Coinage

While empires rose and fell, Greek colonies along the coast of western Turkey (Anatolia) made a discovery that would transform human economics forever. Cities like Miletus and Ephesus, stretching north to Bithynia, created the world's first coins around 600 to 650 BC.

These tiny coins were made of electrum, a natural mixture of gold and silver. Some featured simple designs like a lion's face, while others were just round with a punched dent on the reverse. Because metallurgists had not yet learned to separate gold from silver, the exact value of electrum coins remained somewhat uncertain.

The Economic Revolution: Before coinage, all economic activity operated through barter. This created a fundamental problem that few people consider today: how do you distinguish a slave from an employee when both receive food, clothing, and shelter as payment?

The answer was simple but stark: an employee had the right to quit. A slave did not. In terms of material conditions, both might appear identical. But freedom versus bondage came down to the right to leave.

Coinage eliminated this ambiguity. Now employers could pay wages, and employees could buy their own food, clothing, and shelter. The difference between free and enslaved became immediately visible.

Barter also created absurd inefficiencies. Imagine wanting a dozen eggs but only having a bolt of linen to trade. You visit the egg seller, who does not want linen. So you find someone who wants linen and trades it for salt. Then you return to the egg seller and hope he wants salt. How do you even determine how many eggs equal a bag of salt? The process was a nightmare.

Coins made transactions direct and values measurable. This innovation would prove crucial to the Persian Empire's later success.

Croesus and the Perfection of Coinage

King Alyattes of Lydia, whose kingdom neighbored the Greek colonies, adopted these electrum coins. His son Croesus achieved a technological breakthrough: he discovered how to separate gold from silver in electrum.

This made the kingdom of Lydia extraordinarily wealthy. Merchants preferred Lydian coins because they knew exactly how much gold or silver each contained. Croesus became proverbially rich. Lydian silver coins from approximately 575 BC featured a lion charging a bull, and their purity made them the preferred currency across the ancient world.

Croesus and the Question of Happiness: Before his downfall, Croesus encountered Solon, the wisest man in Athens. Solon had saved Athens from self-destruction during a brutal civil war by creating a republic, then leaving the city to prevent citizens from foolishly electing him king and destroying his creation.

During his travels, Solon visited Lydia. Croesus asked him: "Who is the happiest man on earth?" expecting Solon to acknowledge his vast wealth. Instead, Solon described two young men who carried their frail mother to a ceremony on a litter, then died a few days later. He mentioned a soldier who died in battle defending his city.

Croesus protested, gesturing at his enormous piles of gold. Solon responded with words that would prove prophetic: "We will know whether you were the happiest man on earth when you die, because at that moment we can look at your life and determine. But right now, your story is as yet untold."

This conversation would haunt Croesus after he lost his son to accident, his kingdom to conquest, and his wife to suicide.

The Achaemenid Dynasty and Cyrus's Lineage

The Foundation of Persian Power

A Persian leader named Achaemenes (Hakameish in Persian) emerged as a general during the push against Assyrian control. He may have been legendary rather than historical, possibly created retroactively by later rulers to establish dynastic legitimacy. However, evidence suggests he probably was real, as he conquered approximately half of Elam in southwestern Iran.

The Elamites were a language isolate, meaning no related language exists on Earth. They were neither Aryan nor Semitic but wedged between these two great language families. When the Persians conquered eastern Elam, they established their capital at Anshan, creating the Kingdom of Anshan as a vassal state to the larger Median kingdom.

The Achaemenid family line proceeded: Achaemenes, then Teispes, then Cyrus I, then Cambyses I. Cambyses I would father Cyrus II, who would become Cyrus the Great.

Cyrus's Royal Lineage on Both Sides

Cyrus was born around 600 BC (some sources suggest 590 BC) into remarkable circumstances. His father Cambyses I ruled the Kingdom of Anshan. His mother Mandane was a Median princess, daughter of Astyages, king of the Medes.

When Greeks heard the name "Astyages," they transformed it into "Axyages," demonstrating how names corrupted across languages and cultures. Mandane's mother Aryenis was the sister of Croesus, king of Lydia. This meant Cyrus had royal blood from both Persian and Median lines, plus family connection to the wealthiest kingdom in Anatolia.

The Education That Shaped a Revolutionary

Cyrus spent significant portions of his childhood with his grandfather Astyages, beginning around age six. This extended mentorship proved crucial to his later success. Astyages taught his grandson the Median way of life: eating with hands, talking during meals, making sounds while eating. To young Cyrus, these were not barbaric practices but different cultural expressions.

Beyond etiquette, Astyages provided comprehensive education in leadership. He taught Cyrus hunting, battle tactics, history, mythology, and philosophy. Through years of close contact, Cyrus came to know his grandfather's character intimately and developed profound love and respect for him.

This relationship would later prove critical. When Cyrus decided to unify the Persian and Median kingdoms, he could predict exactly how his grandfather would respond to provocation. This knowledge enabled him to devise a strategy that would seem impossible: defeating his grandfather militarily while preserving their relationship and creating a partnership empire.

Cyrus's Revolutionary Unification Strategy

The Problem of Succession

When Cyrus matured, he decided he would not remain merely king of the small Kingdom of Anshan. He wanted to rule all Persians. However, his father's cousin Arsames held the throne of Persia. Attacking Arsames directly would provoke Astyages, who would send a much larger Median army to punish his grandson's rebellion.

Cyrus understood this with perfect clarity because he knew his grandfather personally. He had lived with Astyages for years, hunted with him, learned from him, and developed deep affection for him. This personal knowledge became strategic advantage.

The Two-Battle Trap

Cyrus devised an elaborate plan. He marched an army into Persia, attacked and captured Pasargadae (the Persian capital), and seized Arsames. Then he immediately retreated with his forces.

Cyrus knew that word would reach Astyages quickly and that his grandfather would send a larger Median army to rescue Arsames and punish this rebellion. He also knew the route this army would take: through Isfahan, down a valley, through a mountain pass on the way to Pasargadae.

Cyrus positioned his forces at that mountain pass and waited. When the Median army arrived, Cyrus ambushed them. The Medes, shocked by this unexpected attack, were defeated and routed back toward Isfahan. This was one of the first times the Medes had ever lost a battle. They were accustomed to victory.

Cyrus pursued his fleeing grandfather and caught him somewhere southeast of Isfahan. He fought Astyages a second time and defeated him again. The old king was stunned. His beloved grandson had just humiliated him twice in battle.

The Unprecedented Reconciliation

After the second defeat, Astyages raised a white flag and approached Cyrus, demanding to know why his grandson had done this terrible thing. Cyrus's response was extraordinary and would define his entire approach to empire:

"You are my grandfather and I love you and I would never do anything to hurt you. I know I have hurt you now, but it is for a greater cause. I am serving the greater good for humanity in this moment."

Cyrus then outlined his plan with stunning boldness. Arsames would not be executed or mutilated (the typical fate of defeated rivals). Instead, he would become a satrap, a provincial governor. He was no longer king of the Persians. Cyrus was.

The Kingdom of Anshan no longer existed as a separate entity. It was annexed. But Astyages would remain king of the Medes. He would not be deposed or humiliated.

The Revolutionary Partnership: Here came the unprecedented element. Astyages and Cyrus would rule together as equals, two kings of equal power jointly governing a united empire. They would build something great together, whether Astyages liked it or not.

This was arguably the worst possible governmental structure. Two rulers of equal power governing a single state creates constant potential for conflict and deadlock, like a marriage where both partners have completely equal authority. Constant argument typically results.

But Cyrus and Astyages made it work because they genuinely loved each other. Their personal bond, built over years of hunting, learning, and shared meals, enabled what should have been an unstable political arrangement. When Astyages died years later, Cyrus became sole emperor, and the Median territories were fully incorporated as satrapies within the empire.

The Philosophy of Conquest: A Revolutionary Approach

The First Conquests: Urartu and Cappadocia

The united Medo-Persian force first conquered Urartu, the Armenian kingdom north of the collapsed Assyrian Empire. They then seized Cappadocia in central Turkey, a region of stunning natural beauty where volcanic activity had created extraordinary rock formations.

These conquests alarmed Croesus of Lydia. His wealthy kingdom now bordered an expanding empire led by a strategically brilliant ruler who happened to be his great-nephew (Cyrus's grandmother Aryenis was Croesus's sister).

Croesus and the Prophecy Fulfilled

Croesus had consulted the Oracle of Delphi, receiving a cryptic prophecy about a great power in the east and something terrible befalling him. The oracle's exact words have been lost to time, but the meaning would only become clear after events unfolded.

Fearing this prophecy, Croesus preemptively attacked the Persian Empire at Pteria. The battle was bloody with massive casualties but ended in a draw. Croesus panicked. His son had died in an accident years earlier, and he remembered Solon's words about only being able to judge a life's happiness at its end.

Believing the oracle predicted his defeat, Croesus set Pteria ablaze and retreated to his capital at Sardis.

The Battle of Thymbra: Strategy Defeats Numbers

Rather than enduring a siege at Sardis, Croesus decided to meet Cyrus in open battle at Thymbra. The size of the opposing armies remains debated. Ancient sources (particularly Xenophon) claimed Croesus commanded over 400,000 men versus Cyrus's slightly under 200,000. Modern historians estimate perhaps 100,000 Lydians against 20,000 to 50,000 Persians.

Regardless of exact numbers, Croesus enjoyed at least 2:1 superiority, possibly as extreme as 5:1. His force was international, including Babylonians and Egyptians, all nervous about this new Persian Empire on their borders.

Cyrus arranged his smaller army in a V-shape with archer towers in the center for elevated firing positions and cavalry on the flanks. Croesus positioned his massive infantry force forward with cavalry on his flanks.

The Psychological Trap: Cyrus's V-formation was deliberately tempting. It appeared vulnerable to a flanking attack. When Croesus launched his cavalry against the Persian flanks, Cyrus waited patiently until the Lydian cavalry was fully committed to combat. Then he sent his own cavalry charging into them.

The Lydian cavalry was forced to retreat in disorder. Cyrus immediately ordered a full-scale attack. The smaller Persian army, better positioned and more cohesively commanded, destroyed the larger Lydian force.

Grace in Victory

Croesus approached under a white flag to surrender. Cyrus's response exemplified a completely new approach to conquest:

"I am not going to hurt you. You are my relative. Why would I hurt you? That's terrible. Do you want to be a minister in my cabinet?"

This was unprecedented. Ancient conquerors typically executed rival kings, enslaved their families, and plundered their cities. Cyrus offered partnership to the defeated.

After Croesus accepted, Cyrus still needed to capture Sardis, which had not surrendered. The Persians built earthen ramps protected by shields so workers could bring dirt without being struck by arrows. Within twelve days, the ramps reached the walls and the Persians captured the city.

Tragically, Croesus's wife panicked during the city's fall and threw herself from the roof. With his son dead from accident, his wife dead from despair, and his kingdom lost, the oracle's prophecy proved grimly accurate: when Croesus crossed the Halys River to attack Persia, a great empire was destroyed, but it was his own, not Cyrus's.

Rebellion and the Completion of Anatolian Conquest

Cyrus appointed a trusted Lydian named Pactyas to collect Croesus's gold and transport it to Pasargadae to become Persian state revenue. Cyrus planned to mint Persian coins eventually but would use Lydian and Ionian coins in the meantime.

Pactyas instead used the gold to hire mercenaries and launched a rebellion to liberate Lydia just weeks after its incorporation into the empire. Cyrus sent General Mazares to suppress the rebellion. Pactyas fled to Greek colonies and hired more mercenaries with Croesus's gold. Mazares defeated him and returned the remaining gold to Pasargadae, ending Lydian resistance.

Mazares continued conquering Anatolia, including Bithynia and other states, until his death. General Harpagus replaced him and completed the conquest of Anatolia, capturing Lycia, Caria, Miletus, Ephesus, and the Greek city-states. These became satrapies within the Persian Empire.

The Revolutionary Principle: Partnership, Not Subjugation

What It Meant to Be Conquered by Cyrus

When Cyrus conquered a territory, he established a radically different relationship with conquered peoples. They received a message that no conquered people had ever heard before:

"You are now part of the Persian Empire with all the rights of membership, as if you were Persians. Armenians have all the rights of Persians. Lydians have all the rights of Persians. You are not subjects. You are partners."

This was revolutionary beyond modern comprehension. Every previous empire had operated on the principle of the conqueror's superiority and the conquered's inferiority. The Romans would later perfect this brutal system: destroy military resistance, enslave massive portions of the population, plunder wealth, then force survivors to Romanize (adopt Roman culture, language, and customs).

Cyrus offered the opposite approach. While the initial act of conquest remained ethically wrong (attacking others is always wrong, in principle), the post-conquest treatment was extraordinary.

The Terms of Partnership:

State coffers were plundered, but individual civilians were not. The wealth of the kingdom became Persian state revenue, but private property was protected.

No cultural subjugation occurred. Conquered peoples were explicitly told to continue speaking their languages, practicing their religions, and maintaining their customs. These were not merely tolerated but celebrated as contributions to imperial diversity.

Local autonomy was preserved. Conquered territories became satrapies (provinces) governed by satraps (provincial governors), often members of local nobility who knew the region and its people. These governors had significant autonomy in local administration while remaining accountable to the central government.

Partnership meant genuine equality. This was not rhetoric. Cyrus created administrative systems, legal protections, and cultural policies that treated formerly separate peoples as equal members of a larger community.

This approach stood in stark contrast to every empire before or since. The underlying principle was both moral and strategic: diversity was strength, partnership created stability, and genuine inclusion generated loyalty that force could never achieve.

The Indian Campaign and Strategic Flexibility

After consolidating control over Anatolia, Cyrus launched a major campaign into India. His armies conquered territory up to the Indus River, incorporating vast regions into the Persian Empire.

When Cyrus crossed the Indus River the first time, he was defeated by fierce resistance. Rather than abandoning the campaign or committing to endless warfare, Cyrus demonstrated strategic flexibility. On a second campaign, he crossed the Indus again but made a crucial adjustment.

Instead of annexing land east of the Indus (which would require permanent military occupation and constant conflict), Cyrus established it as a vassal state. The local rulers remained in power, pledging loyalty and paying tribute to Persia but maintaining internal autonomy. Cyrus then withdrew his main forces.

Everything west of the Indus was fully incorporated into the Persian Empire. The vassal state arrangement east of the river created a buffer zone that prevented future conflict while acknowledging practical limits to direct control.

This decision demonstrated sophisticated strategic thinking. Cyrus understood that empire-building required knowing when to push forward and when to establish stable boundaries. Endless expansion created endless warfare. Strategic boundaries with vassal states created stability.

The Fall of Babylon: Engineering Triumph and Merciful Conquest

The Neo-Babylonian Empire as Final Obstacle

With Anatolia and the Indus Valley secured, Cyrus turned his attention to the last major power in the region: the Neo-Babylonian Empire. This empire controlled all of Mesopotamia, Syria, and Palestine, making it a formidable adversary.

In 539 BC (one of the few firmly dated events in this period), the Persians fought the Battle of Opis. The Neo-Babylonian forces were defeated. Their emperor Nabonidus escaped and fled to another city. Cyrus pursued, captured that city, and continued toward Babylon itself.

The Ingenious Capture of Babylon

Babylon was one of the ancient world's greatest cities, housing approximately 200,000 people. This made it one of the largest urban centers ever built to that point in history. The city's massive walls presented a formidable defensive challenge.

Building earthen ramps (the standard siege technique) would take enormous time and expose workers to constant archer fire from the walls. Cyrus needed a different approach.

The Engineering Solution: The Persians cut a canal and redirected the Tigris River, which flowed through the city. Where the river passed through the walls, gaps existed to allow water flow. Once the water level dropped to less than waist-deep, the Persian army simply marched through these gaps into the city.

Babylon surrendered without a fight. No massacre occurred. No widespread destruction happened. Emperor Nabonidus surrendered and was offered a position in Cyrus's cabinet. The Persian army assumed control of the entire Neo-Babylonian Empire peacefully.

The empire now stretched from Palestine to Pakistan, through all of Anatolia and into parts of Afghanistan. This was the largest empire the world had ever seen.

The Cyrus Cylinder: The First Bill of Rights

The Revolutionary Document

In 539 BC, Cyrus ordered the creation of a clay cylinder inscribed in cuneiform script. This cylinder was written in Babylonian (not Persian), making it accessible to the local population. It was placed in the foundation of the Temple of Marduk as part of the construction sacrifice.

Archaeologists discovered this cylinder with no prior knowledge of its existence. What they found was revolutionary: the world's first bill of rights.

The text now appears in six languages above the entrance to the United Nations building in New York, recognized as a foundational document in the history of human rights.

A second copy was later discovered in Kashan, written in Elamite on a square tablet. This confirmed that Cyrus distributed his bill of rights in every language of the empire, ensuring all peoples could read and understand their rights.

The Three Revolutionary Rights

1. Freedom of Religion (Beyond Tolerance to Active Support)

Cyrus did not merely grant people the right to worship as they chose. He went much further. The empire would actively maintain temples of all religions. If temples were broken or destroyed, the empire would rebuild them.

This was extraordinary. Cyrus was Zoroastrian, yet he provided state funding for temples of all faiths throughout the empire. He believed that religious practice benefited people and society, and that supporting diverse religious traditions strengthened rather than weakened the empire.

As the cylinder states, Cyrus sought "the safety of the city of Babylon and all its sanctuaries." He portrayed himself not as a conqueror imposing foreign beliefs but as a protector chosen by Babylon's own god Marduk to restore order and justice.

2. Abolition of Slavery

Understanding this right requires careful definition given the economic context. In a barter economy without widespread coinage, distinguishing slaves from employees was difficult. Both received food, clothing, and shelter. The fundamental distinction was simple: employees could quit, slaves could not.

Cyrus banned slavery throughout the empire. However, he did maintain a category called serfs, specifically for prisoners of war he feared would become rebels if fully freed. Serfs were essentially free people who could not leave their farms. They could earn income and receive a share of what they produced, unlike slaves who merely stayed alive through their master's provision.

This mirrors the distinction Europeans later made between Russian serfs and chattel slaves. Serfs had limited freedom but genuine economic participation. They were not property.

The cylinder explicitly states that Cyrus "freed [the people] from their bonds," ending the brutal systems of forced labor that previous empires had maintained.

3. Prohibition of Human Sacrifice

Most civilizations in the region practiced human sacrifice: Assyrians, Greeks, Romans. Archaeological evidence includes a 12-year-old boy's skeleton at the foundation of Zeus's temple, sacrificed and then built over.

Cyrus declared this practice finished. No more human sacrifice would occur in the Persian Empire. This represented a profound statement about human dignity and the sanctity of human life.

The Conceptual Revolution: Limits on State Power

The truly revolutionary element was not just these specific rights but the underlying principle: state power has limits.

No one had previously conceived that a king or state could be constrained by law or principle. Kings ruled absolutely. Their will was law. Their power was unlimited.

Cyrus, who was himself an absolute monarch without a parliament or legislature, voluntarily granted these rights to all people in his empire. He declared that even he, as emperor, could not violate these protections.

This was the birth of constitutional government, the idea that fundamental principles exist above and beyond the ruler's personal authority.

The Philosophy of Diversity as Imperial Strength

The Sophisticated Theory

Cyrus articulated a remarkably sophisticated understanding of why diversity strengthens rather than weakens a society:

"Our diversity is what makes us strong. If we have one culture and one language and one religion and a crisis happens, there is one answer we will come up with. But if we have 50 languages and 50 cultures and 50 religions and a crisis comes up, we will have 50 answers, and maybe one of them will be good. If we are lucky, we will get five good ones and we can experiment."

This was systems thinking applied to imperial governance 2,500 years before the term existed. Cyrus understood that:

Homogeneity creates fragility. A single approach to problems means a single point of failure. If that approach proves wrong, the entire system collapses.

Diversity creates resilience. Multiple perspectives generate multiple potential solutions. Even if most prove ineffective, some will work, and the system can adapt.

Innovation requires variation. New ideas emerge from combining different traditions, perspectives, and knowledge systems. A culturally uniform empire cannot innovate as effectively as a diverse one.

Visual Representation at Persepolis

Artwork at Persepolis (built by later Persian kings) depicts this philosophy visually. Reliefs show representatives of all the empire's nations holding hands as they process together, each dressed in their traditional clothes.

Arabs appear in Arab dress. Afghans in Afghan clothing. Jews in Jewish garments. Armenians in Armenian style. Lydians in their traditional fashion. Each distinct, each honored, each participating as equals in the imperial community.

This was not assimilation. This was celebration of difference as contribution to collective strength.

The contrast with later empires is stark. Romans demanded Romanization. Chinese empires demanded adoption of Chinese culture. Islamic empires demanded conversion or subordinate status. European colonial empires demanded total cultural surrender.

Cyrus demanded nothing except loyalty and tax payment. Everything else, people could keep and celebrate.

The Liberation of the Jews and the Temple Reconstruction

Reading the Cylinder and Seeking Confirmation

When the Cyrus Cylinder was placed in the Temple of Marduk, news of its contents spread throughout Babylon. Jewish captives, who had been living in Babylon since the destruction of Solomon's Temple decades earlier, read the cylinder's promises with astonishment.

They approached Cyrus and asked directly: "Is this genuine? Do these promises apply to us?"

Cyrus confirmed they did. The Jews explained they were captives, brought to Babylon against their will. Cyrus's response was immediate:

"Not anymore. You are free. You can live anywhere you want."

The Invitation and the Return

Cyrus then made an invitation. He valued Jewish culture and learning. If some were willing, he would greatly appreciate a Jewish community establishing itself in Isfahan. Some accepted this invitation, and their descendants remain in Isfahan today, maintaining Jewish traditions for over 2,500 years.

The majority of Jews wished to return to Palestine, to their ancestral homeland. Cyrus agreed without hesitation: "Absolutely. I will help you get there if you need support."

The Temple Reconstruction: Sincerity Proven Through Action

The Jews mentioned the religious freedom provision about rebuilding temples. The Neo-Babylonians had not merely destroyed Solomon's Temple but had demolished the entire platform on which it stood, the Temple Mount.

Cyrus asked for the architectural plans. Jewish architects drew up designs showing a giant human-made mesa (a flat-topped elevated platform) with the temple built on top.

When Cyrus saw that the Babylonians had destroyed not just a building but an entire artificial mountain, he recognized the extraordinary hatred that must have motivated such thoroughness. He declared:

"I only know one people on the entire planet who can build mountains."

Cyrus sent a delegation to Egypt and hired Egyptian engineers, who were the ancient world's masters of massive construction projects (having built the pyramids). These engineers came to Jerusalem and built the Temple Mount, creating an enormous artificial platform. Then they constructed Solomon's Second Temple on top of it.

The remarkable elements of this decision:

Cyrus used Persian state revenue (including the gold confiscated from Croesus) to fund the project. He did not ask the Jews to pay for their own temple's reconstruction.

He hired the best engineers available, regardless of cost, to ensure the work was done to the highest possible standard.

He demonstrated that his religious freedom commitments were not merely words but sincere policy backed by substantial resources.

The Romans would later destroy this Second Temple (in 70 AD), but for over 600 years it stood as a monument to Cyrus's genuine commitment to religious freedom and cultural restoration.

Recognition in Jewish Scripture

The Jewish Bible includes extensive praise of Cyrus, using the name "Koresh" (the Hebrew rendering of his name). He appears in multiple books, always favorably.

Most remarkably, the Book of Isaiah calls Cyrus "the Lord's anointed," using the Hebrew word that gives us "messiah." Cyrus is the only non-Jewish person in the entire Bible granted this messianic status.

This recognition demonstrates the profound impact his policies had. For a monotheistic people who believed they were God's chosen nation, to grant messianic recognition to a foreign, non-Jewish king represented extraordinary acknowledgment of his righteousness and justice.

The Administrative Revolution: Federal Empire

The Satrapy System

Cyrus created an administrative innovation that would define the Persian Empire for centuries: the satrapy system. The empire was divided into provinces (satrapies), each governed by a satrap (provincial governor).

Key features of this system:

Local Knowledge: Satraps were often members of local nobility who understood the region's culture, languages, and customs. This ensured governance was informed rather than ignorant.

Significant Autonomy: Satrapies maintained substantial independence in local administration. They could keep their own laws, educational systems, languages, and even local military forces.

Central Accountability: While autonomous in local matters, satraps remained accountable to the central government for tax collection, maintaining order, and implementing imperial policy.

Balance of Power: The system balanced imperial control with local self-governance, preventing both anarchic fragmentation and oppressive centralization.

An Early Federal System

The Persian Empire under Cyrus functioned as an early form of federal government. Each of the many territories enjoyed genuine internal autonomy. They could:

Maintain their own legal systems, as long as these did not conflict with the fundamental rights in the Cyrus Cylinder.

Continue their own educational traditions and teach in their own languages.

Practice their own religions without interference or pressure to convert.

Retain local military forces for regional defense, supplementing the imperial army.

Govern themselves according to traditional customs and practices.

The empire even maintained something resembling a "courthouse" where, at least in theory, even kings could be held accountable for wrongdoing. This suggested an embryonic concept of judicial review, where actions could be evaluated against established principles rather than purely at the ruler's discretion.

The Pragmatic Wisdom of Autonomy

This federal approach was both morally enlightened and strategically brilliant. As long as territories paid taxes and did not rebel, they were free to live as they had before conquest. This created several advantages:

Reduced Resistance: People were far more willing to accept Persian rule when their cultures were respected rather than destroyed.

Efficient Governance: Local governors who understood their regions could administer more effectively than distant Persian bureaucrats ignorant of local conditions.

Economic Prosperity: Cultural stability allowed trade and economic activity to flourish rather than being disrupted by constant conflict.

Information Flow: Diverse perspectives provided better intelligence about threats, opportunities, and emerging issues throughout the empire.

Cyrus understood that a content populace formed the backbone of a strong empire. This was not weakness disguised as mercy. As one ancient observation noted, "Only the strong can be tolerant." Cyrus's restraint was a mark of strength, confidence, and wisdom.

The Origins of Cyrus's Principles

The Zoroastrian Influence

Understanding why Cyrus governed as he did requires examining the religious and philosophical traditions that shaped Persian culture. The most significant influence was Zoroastrianism, founded by the prophet Zoroaster (Zarathustra in its original form).

Core Zoroastrian Concepts:

Asha versus Druj: The fundamental cosmic struggle between asha (truth, order, righteousness) and druj (the Lie, chaos, injustice). This was not merely an abstract philosophical concept but a moral framework for evaluating all actions and decisions.

The Righteous Ruler: In Zoroastrian thought, a just king aligns with asha, governing truthfully and righteously. A tyrant who lies, abuses power, and creates chaos embodies druj. Kingship carried profound moral responsibility.

Ethical Dualism: The universe was engaged in an ongoing battle between good and evil, truth and falsehood, order and chaos. Every person, especially rulers, participated in this cosmic struggle through their choices and actions.

Divine Support for Justice: Rulers who governed according to asha received divine support from Ahura Mazda (the supreme God in Zoroastrian belief). Those who ruled through druj would ultimately fail, regardless of temporary success.

Later Persian kings made these concepts explicit. King Darius I's Behistun Inscription declares: "I ruled by the grace of Ahura Mazda" and "I was not deceitful, I was not wicked. I governed according to asha."

These were not new ideas suddenly invented by Darius. They represented continuation of foundational Persian values that Cyrus had embodied in his governance. While Cyrus left fewer written records than Darius, his actions demonstrated these principles in practice.

Religious Tolerance Rooted in Spiritual Confidence

Cyrus's approach to religious diversity reflected sophisticated theological thinking. While he himself honored Ahura Mazda and ruled according to Zoroastrian principles, he did not enforce Zoroastrian worship on subject peoples.

Historical records confirm: "While he himself ruled according to Zoroastrian beliefs, he made no attempt to impose Zoroastrianism on the people of his subject territories."

This reflected profound spiritual confidence. Cyrus believed that truth and justice would prevail through example, not coercion. He understood that genuine faith cannot be forced. Loyalty earned through respect would always prove stronger than compliance extracted through fear.

This stands in stark contrast to later rulers. King Xerxes, for example, showed less tolerance, removing statues of certain foreign gods, perhaps reflecting a more assertive Zoroastrian stance. This highlights how exceptional Cyrus's open-mindedness was, even within the Persian tradition.

The Practical Foundations

Cyrus's principles also had deeply pragmatic roots. Ruling the largest empire in history required managing extraordinary diversity. A policy of inclusion and local autonomy secured loyalty far more effectively than brutality.

Strategic Benefits of Tolerance:

Reduced Rebellion: Content populations had little motivation to rebel. The cost of maintaining order dropped dramatically when people willingly accepted Persian rule.

Co-opted Elites: By working with local leaders, priests, and nobility rather than suppressing them, Cyrus ensured that influential figures had a stake in the imperial system's success.

Buffer States: Freed populations like the Jews in Palestine became grateful allies. Cyrus strategically positioned returned Jews as a friendly buffer between Persia and Egypt, turning former captives into geopolitical assets.

Economic Integration: Stable, prosperous provinces generated more tax revenue than plundered, rebellious ones. Economic integration benefited both the empire and its constituent peoples.

As one analysis observes, Cyrus understood that "refraining from the exercise of cruel power" was actually a demonstration of strength, not weakness. His restraint unified the empire more effectively than terror ever could.

The Synthesis of Principle and Pragmatism

Cyrus's guiding principles emerged from the confluence of ethical teachings and practical statecraft. Zoroastrian emphasis on truth, justice, and the king's duty to uphold asha provided a philosophical foundation for fair and tolerant rule.

Meanwhile, Cyrus's experiences as a conqueror taught him that generosity could build an empire stronger than fear. This was not naive idealism. It was hardheaded strategic thinking informed by moral principles.

The blend of idealism and pragmatism defined his governance. He believed in the rightness of his principles and also recognized their practical superiority. Justice was both morally correct and strategically effective.

Cyrus's Death: The Final Campaign

The Scythian Campaign

After consolidating the empire from Palestine to Pakistan and through all of Anatolia, Cyrus decided to campaign against the Scythians (Saka) in Central Asia. He captured substantial territory in Afghanistan while fighting these fierce steppe warriors.

During these campaigns, Cyrus killed the king of the Massagetae (a powerful Scythian confederation in modern Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan) and also killed a king in northern Pakistan.

Two queens, each seeking vengeance for their fallen husbands, met and planned together. Queen Sparethra of northern Pakistan and Queen Tomyris of the Massagetae coordinated their forces to set an ambush for the Persian army.

The Battle and the End

By this point, Cyrus was an old man, probably around 60 years old (some sources suggest 70). Despite his age, he personally led his army into what is now Uzbekistan in approximately 530 BC.

The combined forces of Tomyris and Sparethra defeated the Persian army in battle. Cyrus was killed during the fighting.

The Vengeful Aftermath

Tomyris sought vengeance. She had lost her husband and her sons fighting Cyrus. She had watched her people suffer in these wars. After the battle, she found Cyrus's body and personally decapitated him.

She poured wine into an animal skin, dropped Cyrus's head inside, tied it closed, and threw it into a river. This was her final statement: the great conqueror who had shown mercy to so many had met a merciless end at the hands of those he sought to conquer.

Some ancient accounts, particularly Xenophon's, claim Cyrus died peacefully in his capital of Pasargadae. Most traditions, however, agree he fell in combat against the Massagetae. The archaeological and historical consensus supports the violent death in Central Asia.

The Principle Remains

The manner of Cyrus's death does not diminish the extraordinary nature of his life and governance. He died as many ancient kings did, in battle against fierce enemies. But he lived as no king before him had, creating an empire based on partnership rather than subjugation.

The attacking party is always wrong, in principle. Cyrus attacked, conquered, and expanded through military force. That remains ethically problematic. But what he created in the process, the revolutionary principles he established, the human dignity he protected, these transformed human governance forever.

The Empire's Continuation Under Cambyses II

Despite Cyrus's death, the empire he built survived and even expanded. The throne passed to his son Cambyses II, who proved himself a capable, if less innovative, ruler.

Cambyses decided the Scythians in Central Asia were not worth continued warfare. Instead, he turned his attention to the last major unconquered power in the region: Egypt.

The Egyptian Campaign: Cambyses successfully conquered Egypt, bringing the ancient civilization along the Nile under Persian control. He then extended Persian rule into Cyrenaica (eastern Libya) and Nubia (northern Sudan).

This brought the Persian Empire to its maximum territorial extent, stretching from the Indus River in the east to Cyrenaica in the west, from the Caucasus Mountains in the north to Nubia in the south. The empire now controlled territory from modern Pakistan to modern Libya, encompassing dozens of nations, hundreds of languages, and countless religious traditions.

Cambyses ruled for only a few years before his death, leaving the question of succession uncertain.

The Constitutional Debate

After Cambyses died, Persian leadership faced a critical choice. Generals and satraps, including the future King Darius, gathered to determine the empire's political structure.

By this point, Cyrus's principles had transformed even his initially skeptical followers. Many had questioned why Persians should treat conquered peoples as equals. But decades of experience had proven Cyrus right. The empire was stable, prosperous, and strong precisely because of its inclusive policies.

The council members wanted to continue Cyrus's vision but debated the best governmental form. They discussed three options:

Actual Democracy: Direct popular voting on policy, with no elections (elections exist in republics to choose representatives; democracies have no elections because people vote directly on policies).

Electoral Republic: Representatives elected by the people to make decisions on their behalf, either through popular vote or hereditary succession.

Continued Monarchy: A single ruler with absolute authority, governing according to established principles.

This debate occurred before Athens became a democracy. Solon had created a republic in Athens decades earlier, but Cleisthenes had not yet convinced Athenians to adopt direct democratic governance. The Persian leadership was considering these options independently, not copying Greek models.

After extensive deliberation, they chose to continue the monarchy. Darius became the next emperor, and he would prove to be one of Persia's greatest rulers, expanding on Cyrus's administrative systems, building roads, establishing a postal service, and creating standardized laws.

The Legacy: Why Cyrus Still Matters

Ancient Recognition

Cyrus earned extraordinary recognition in his own time from peoples across the ancient world:

The Persians fondly called him "father" for his benevolent leadership and the pride they felt in the empire he created.

The Greeks hailed him as "a worthy ruler and lawgiver," remarkable given Greek prejudices against "barbarian" (non-Greek) peoples. The Greek historian Xenophon wrote the "Cyropaedia," portraying Cyrus as the ideal ruler who governed by persuasion and example rather than force.

The Jews revered him as "the Lord's anointed," the only non-Jewish figure granted messianic status in the Bible, in recognition of his liberation of their people and reconstruction of their temple.

The Babylonians welcomed him as a liberator chosen by their own god Marduk to restore order and justice after years of incompetent rule.

The Lydians, Armenians, Egyptians, and countless other peoples incorporated into the empire acknowledged him as a just ruler who respected their dignity even in conquest.

Even the Romans, who came centuries later and normally scorned foreign kings, admired Cyrus as a model ruler. His reputation transcended cultural boundaries because his principles addressed fundamental human needs: dignity, freedom, justice, and respect.

Alexander's Acknowledgment

Two centuries after Cyrus's death, Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire. When Alexander reached Pasargadae, he paid respects at Cyrus's tomb and reportedly modeled aspects of his own policy on Cyrus's example of combining military power with generous treatment of conquered peoples.

Alexander's acknowledgment demonstrated that even a conqueror recognized the wisdom in Cyrus's approach. Military victory was temporary. Building lasting systems of governance required the kind of inclusive, respectful policies Cyrus had pioneered.

Medieval and Renaissance Influence

Through Greek and Roman writings, Cyrus's fame as a wise and benevolent conqueror entered Western political imagination. Medieval and Renaissance thinkers studied ancient accounts of his governance, drawing lessons about leadership, justice, and the relationship between rulers and ruled.

The American Founding Fathers read Xenophon's "Cyropaedia." Thomas Jefferson owned multiple copies. The book influenced their thinking about how leaders could secure voluntary loyalty by respecting people's rights and beliefs rather than ruling through fear and coercion.

This represented a remarkable chain of influence: a 6th century BC Persian king's principles, transmitted through Greek writings, studied by 18th century American revolutionaries designing a new form of government. Cyrus's ideas about limiting state power and protecting individual rights echoed across 2,300 years.

Modern Human Rights Recognition

In the 19th century, archaeologists rediscovered the Cyrus Cylinder. Its translation revealed the extraordinary nature of Cyrus's bill of rights. While scholars caution that the modern concept of human rights did not exist in the 6th century BC, the principles Cyrus established resonate powerfully today:

Freedom of worship and active state support for religious diversity.

Freedom from slavery and forced labor, with human dignity protected by law.

Prohibition of human sacrifice, affirming the sanctity of human life.

Limits on state power, establishing that even absolute monarchs could not violate fundamental rights.

Cultural autonomy and celebration of diversity as societal strength.

These principles found later expression in documents like the Magna Carta (1215 AD), the English Bill of Rights (1689 AD), and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948 AD). While Cyrus's cylinder was not a direct influence on these documents (it remained buried and unknown until the 19th century), it represented humanity's first articulation of these fundamental concepts.

The United Nations recognized this historical significance by displaying the Cyrus Cylinder's text in six languages above the entrance to its headquarters. The cylinder is often called "the first Declaration of Human Rights," symbolic recognition of Cyrus's revolutionary principles.

Contemporary Relevance

In 1971, the Shah of Iran cited the Cyrus Cylinder in celebrations, and October 29 (the traditional date of Cyrus's coronation) is sometimes honored as "Cyrus the Great Day" or "Human Rights Day."

Cyrus's tomb at Pasargadae remains a powerful national symbol in Iran, visited by people who see him as a foundational figure of Iranian identity and statehood. Millions refer to him as "Father Cyrus," maintaining reverence for his vision of just rule across 2,500 years.

The Enduring Questions

Cyrus's legacy raises profound questions that remain relevant today:

Can diverse peoples live together in a single political community? Cyrus proved they could, governing 44% of the world's population (approximately 59 million of 112 million people) with remarkable stability through policies of inclusion and respect.

What makes a government legitimate? Cyrus demonstrated that legitimacy comes from serving people, protecting their dignity, and respecting their autonomy, not from terrorizing them into submission.

Is diversity a weakness or a strength? Cyrus argued persuasively that 50 different cultures facing a crisis would generate 50 potential solutions, while a homogeneous culture would generate only one. Modern research on innovation and problem-solving confirms his insight.

How should power be limited? Cyrus established that even absolute rulers should voluntarily constrain their power according to fundamental principles. This planted the seed for constitutional government and the rule of law.

Can conquest ever be ethical? Cyrus's example suggests that while the initial act of attacking others remains wrong in principle, post-conquest treatment matters enormously. Partnership is morally superior to subjugation, even if conquest itself cannot be fully justified.

Conclusion: The Revolutionary Who Changed Governance Forever

Cyrus the Great ruled for approximately 20 years, from roughly 550 BC to 530 BC. In historical terms, this was a brief period. Yet its impact echoes through 2,500 years of subsequent human history.

He created the largest empire the world had seen to that point, not as an end in itself but as a platform for revolutionary principles of governance. He demonstrated that:

Diversity strengthens societies when differences are celebrated rather than suppressed.

Individual rights exist independent of state power and should be protected by law.

Religious freedom includes not just tolerance but active support for all faiths.

Cultural autonomy enables people to maintain their identities while participating in larger political communities.

State power has limits that even absolute rulers should respect.

Partnership creates stability more effectively than subjugation and terror.

Human dignity must be protected regardless of people's origins or beliefs.

These were not abstract philosophical concepts to Cyrus. They were practical policies implemented throughout his empire, backed by substantial resources, and enforced through administrative systems that outlasted his death by centuries.

The moral complexity of his legacy remains. He was a conqueror who attacked others, and that act of aggression was ethically wrong. Many people died in his campaigns. Families were destroyed. Cities were besieged. The principle holds: the attacker is always wrong.

But what he built through those conquests was extraordinary. He showed humanity a better way to organize diverse peoples, protect human dignity, and govern with justice rather than terror. He proved that tolerance was not weakness but strength, that respecting differences created unity more lasting than forced uniformity.

Future empires would sometimes echo elements of his approach, though rarely as consistently or genuinely. The Romans valued legal plurality but brutally exploited conquered peoples. Islamic empires protected "People of the Book" but maintained explicit hierarchies. European colonial empires demanded total cultural surrender. None matched Cyrus's comprehensive vision of genuine partnership and equality.

His influence extends beyond specific policies to fundamental concepts about human society. The idea that government legitimacy comes from serving people rather than dominating them. The principle that diversity generates resilience and innovation. The understanding that force can conquer but only justice can build lasting peace.

Today, when we debate immigration policy, religious freedom, cultural integration, minority rights, and the limits of government power, we engage with questions Cyrus first addressed 2,500 years ago. His answers remain surprisingly relevant: celebrate diversity, protect dignity, limit power, respect autonomy, build partnerships.

We live in a world of nation-states, many claiming ethnic or cultural homogeneity as their basis for existence. Cyrus demonstrated that a different model is possible: political unity across cultural diversity, strength through variation, stability through respect.

The challenge he poses to us is clear. If one man 2,500 years ago, leading an absolute monarchy without modern technology or communication systems, could govern half the world's population with tolerance and respect, what excuse do we have for failing to do the same today?

His tomb at Pasargadae has stood for over 2,500 years, a monument to principles that transcend time and culture. The inscription attributed to it (though possibly added later) captures his legacy perfectly:

"O man, whoever you are and wherever you come from, for I know you will come, I am Cyrus who won the Persians their empire. Do not therefore begrudge me this bit of earth that covers my body."

This simple humanity, this acknowledgment of shared mortality and common human experience, characterized Cyrus's approach to governance. He saw conquered peoples not as inferior beings to be exploited but as fellow humans deserving of dignity and respect.

That revolutionary vision, first articulated in clay cylinders buried in temple foundations, now stands above the United Nations headquarters, reminding us of principles discovered long ago but still imperfectly implemented. Cyrus the Great showed us what is possible. The question remains whether we will finally learn the lesson.