Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work

AI's ultimatum: A future of amplified human genius or mass job obsolescence? The choice will define our economy, our careers, and our very purpose. We must navigate this revolution wisely, for humanity's future hangs in the balance.

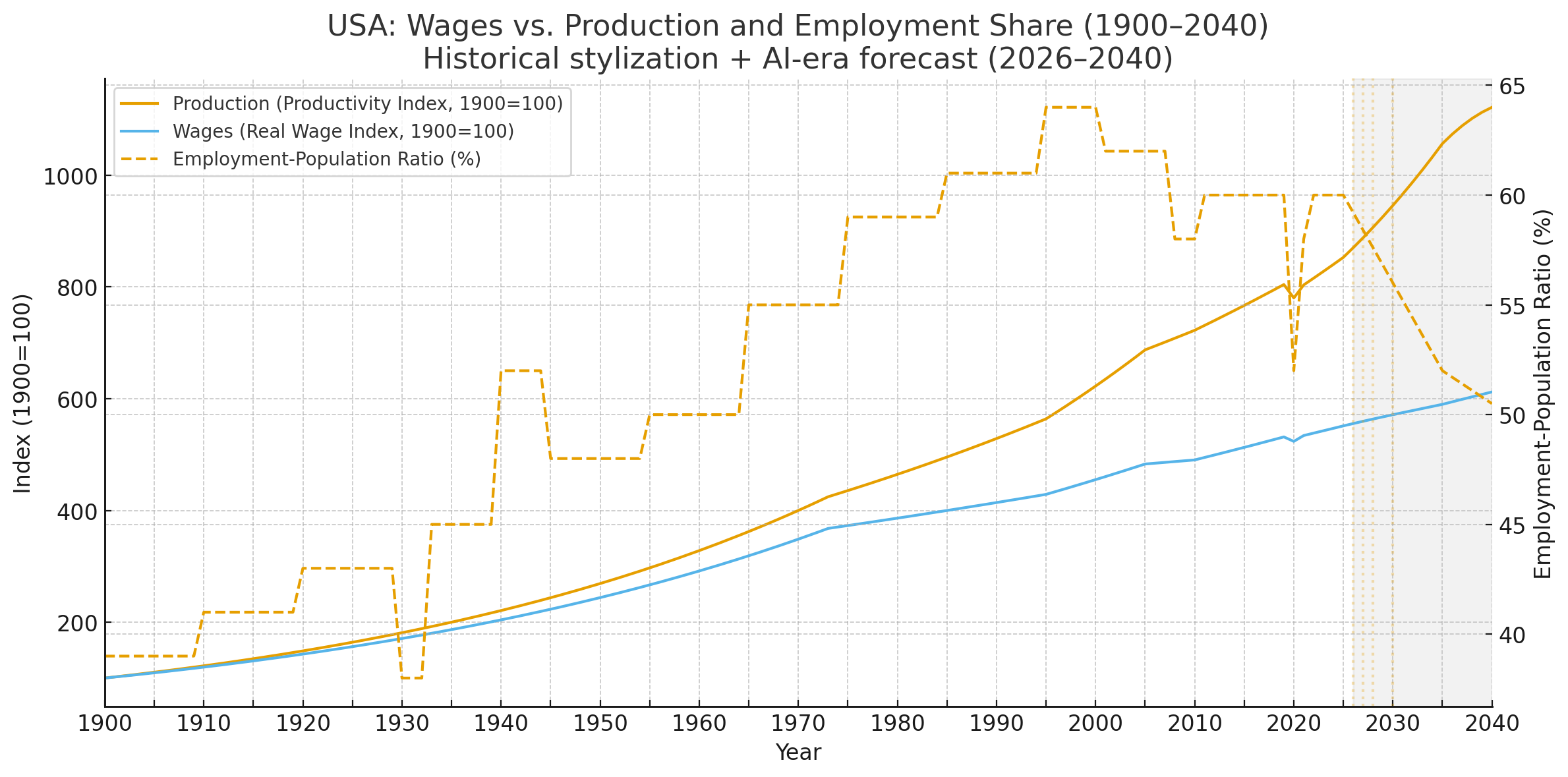

For decades, a simple promise underpinned the American economy: as the nation produced more, its workers earned more. This chart reveals how that promise began to fracture in the latter half of the 20th century starting after 1971 when the Powell memo was produced, as productivity gains (the solid orange line) soared away from real wages (the blue line).

Now, as we enter the AI era, we are confronted with a forecast that threatens to shatter that promise entirely. Productivity is projected to explode to unprecedented heights, yet this growth may come at a devastating cost: a sharp, historic decline in the share of the population with a job (the dashed line).

This visual presents the central dilemma of our time: Will AI be a tool for universal prosperity, or will it create a world of immense wealth for a few while leaving the majority behind? The diverging paths on this chart represent the two futures we must now choose between, setting the stage for a critical analysis of the choices that lie ahead.

The 2020 Fulcrum: When Musical Chairs Became Economic Doctrine

This chart reveals a century-long transformation in the relationship between production, compensation, and employment, with 2020 emerging not as an anomaly but as a compressed demonstration of forces that the forecast projects will unfold systematically through 2040.

For seven decades, productivity and wages moved in near-lockstep, the signature pattern of industrial capitalism's implicit social contract: technological progress meant broadly shared prosperity. That coupling fractured in the 1970s, creating the now-familiar divergence where productivity climbs while wages plateau. But the employment trajectory tells a more unsettling story.

The employment-population ratio oscillated through economic cycles but maintained basic stability, until the forecast period beginning around 2026. The projected decline from roughly 60% to 52% by 2035 represents a structural shift, not a cyclical downturn. The productivity curve continues its acceleration even as tens of millions transition out of traditional employment, suggesting an economy increasingly capable of generating output with progressively less human labor input.

2020 serves as proof-of-concept. The pandemic forced an unplanned experiment in economic elasticity,how much employment could compress before output suffered critically. Remote work adoption, automation acceleration, and supply chain restructuring weren't temporary adaptations but demonstrations that production functions could operate with fundamentally different labor coefficients. Companies discovered that physical presence and employment were more separable than institutional inertia had assumed.

The musical chairs metaphor becomes literal in this projection: the game's structure now guarantees exclusion. Unlike previous technological disruptions that destroyed jobs in one sector while creating them in another, AI and automation appear as horizontal forces affecting cognitive labor across industries simultaneously. The result is not economic stagnation but rather abundance without employment—productivity that keeps playing even after the music stops.

A Comprehensive Analysis

Perspectives on Employment, Economic Transformation, and Social Adaptation

Divergent Perspectives on AI's Employment Impact

The Pessimistic View: Displacement of Half the Workforce

One perspective argues that it is inevitable that machines will displace at least half the workforce, and possibly more. This view, developed over 16 years of analysis, stems from the prediction that AI and robotics will reach a point where they match and then exceed the capability of most typical average workers. The core concern is that for the majority of people who come to work and perform relatively routine, predictable tasks, machines will simply become better at just about everything these workers can do, making it very difficult for them to find a market for their skills.

This perspective emphasizes that while not everyone will lose their jobs, those with particular talents, personality traits, and unique capabilities will have better prospects. However, for the broader workforce performing standard tasks, the outlook is concerning. The fundamental issue is that AI represents a technology that directly challenges humanity's core competence: intelligence and cognitive capability. Unlike previous technological revolutions that automated physical labor, AI targets the very thing that has historically allowed humans to adapt and remain relevant in the workforce.

The Optimistic View: Technological Progress as Economic Growth

The contrasting perspective emphasizes that true economic growth comes from only one source: technological progress. This view holds that if society wants to produce more using fewer resources—including human labor, energy, and capital—the only way to achieve this is through technological advancement. AI represents a huge leap forward in this progress.

However, this optimistic stance comes with important caveats. The proponent of this view explicitly states they don't want to overstate their optimism. They acknowledge that in almost every period of huge technological progress throughout history, society has moved to a better era, but these transitions have caused significant pain along the way. The example of the Industrial Revolution is instructive: while economists describe it as fantastic economic progress, they often overlook the harsh realities documented by writers like Charles Dickens. The human cost during transitions can be substantial.

The key insight from this perspective is that managing the downsides of technological change is the critical task for society and policymakers. The benefits of AI are not in question; rather, the challenge lies in ensuring these benefits are distributed fairly and that the transition period doesn't leave vulnerable populations behind.

AI as a Unique Technological Revolution

Direct Challenge to Human Comparative Advantage

AI is fundamentally different from previous technological innovations. Throughout history, automation has replaced physical labor and routine manual tasks, but humans could always adapt by leveraging their cognitive capabilities. AI changes this dynamic entirely. For the first time, technology is advancing to displace what sets humans apart: our intelligence and cognitive capability. This is our comparative advantage, and AI directly targets it.

This makes AI unique among all technologies. Previous innovations required humans to shift from physical work to cognitive work. AI challenges the foundation of human adaptability itself. When machines can think, reason, and solve problems as well as or better than humans, the traditional escape route of moving to more intellectually demanding work becomes less viable.

Comparison to Internet and Computing Revolution

There is debate about whether AI represents a truly revolutionary change or more incremental progress similar to the internet. The internet brought massive changes but didn't fundamentally alter how lawyers, accountants, or plumbers do their core jobs. However, one perspective challenges this characterization, arguing that computing and the internet have fundamentally transformed knowledge work.

Consider academic work: the number of papers academics can now write has increased dramatically because of computing power. Researchers can access and download census data during a podcast conversation, whereas just a couple of generations ago, obtaining census data was a laborious process involving punch cards. This accessibility has fundamentally changed productivity and made jobs better in many ways. The question is whether AI will have similarly transformative—or even more dramatic—effects across all sectors of the economy.

The Scope of Change: Walmart CEO's Assessment

Walmart CEO Doug McMillan recently stated that AI is going to change literally every job. This raises the question of whether such claims are accurate or hyperbolic. The discussion suggests that while AI may not completely transform every single job function, its impact will be far-reaching and significant. The technology's ability to handle cognitive tasks means that even jobs we might consider relatively safe from automation could see substantial changes in how they're performed.

Historical Parallels and Agricultural Transformation

History provides crucial context for understanding potential AI-driven changes. Agriculture offers the most dramatic parallel: at one point, almost all people on the planet worked in agriculture. The share of the global population engaged in farming has plummeted dramatically, yet this massive displacement didn't result in permanent widespread unemployment. Instead, humanity found new types of work.

However, the transition wasn't smooth or painless. The jobs people initially left farms for—primarily in factories—were not necessarily better at first. Early industrial work often featured harsh conditions, long hours, and didn't immediately improve living standards. Only over time did working conditions improve and new opportunities emerge that were genuinely better than agricultural labor.

Today, many people work in jobs that didn't exist generations ago. Creating podcasts, teaching at universities, and countless other modern professions represent work that our ancestors couldn't have imagined. Most people today would much rather have contemporary jobs than work in fields. This historical perspective suggests that while AI may eliminate many current jobs, entirely new categories of work may emerge.

The critical questions become: What new things will arrive? At what pace will they arrive? Will we like these new jobs? Are they better than the ones they replace? The importance of managing the transition period cannot be overstated, as history shows transformation takes time and can cause significant hardship before benefits materialize.

The Economics of Wage Competition and Displacement

Cost Competition: Machines Must Be Cheaper, Not Just Capable

An important economic principle governs whether AI will actually replace human workers: it's not enough for machines to be able to do a job—they must be able to do it cheaper than humans. This creates a potential scenario where instead of mass unemployment, we might see widespread wage depression. Humans could retain their jobs by accepting significantly lower compensation.

This wage competition dynamic means that white-collar workers, in particular, may face downward pressure on their salaries. Before we see widespread unemployment affecting 50% of the population, we're likely to see real reductions in the compensation people receive. This represents a different but equally concerning form of economic disruption.

Historical examples support this pattern. There are still people using manual carpet weaving looms today, despite mechanized alternatives existing, because human weavers are cheaper than the mechanized production in certain contexts. The interaction of technology capability with cost considerations determines actual displacement patterns, not capability alone.

The AI Investment Bubble Risk

Beyond direct job displacement, there's concern about an AI investment bubble. If this bubble bursts, it could be devastating to the economy. The technology sector's enthusiasm for AI has driven massive investment, and a sudden collapse in confidence or valuation could trigger broader economic disruption. This risk exists alongside and potentially compounds the employment challenges AI presents.

Differential Impacts Across Job Categories

White-Collar Work: Unexpected Vulnerability

Initial concerns about AI focused primarily on white-collar cognitive work, and these concerns remain valid. Knowledge workers who process information, analyze data, write reports, and perform other intellectual tasks find themselves in AI's direct line of fire. These jobs were once considered safe from automation precisely because they required human intelligence and judgment. AI challenges this assumption.

The vulnerability of white-collar work means that college-educated professionals with historically stable careers may face unprecedented disruption. Lawyers, accountants, financial analysts, writers, and many other professional categories could see significant portions of their work automated or augmented by AI systems.

Robotics and Physical Labor Automation

While AI gets significant attention, robotics is making enormous parallel progress and shouldn't be left out of the discussion. The way robotics is advancing is significant for blue-collar and physical work. In environments like Amazon warehouses, robotic systems are already quite disruptive. Observations from even a decade ago showed clearly which direction warehouse automation was headed in terms of reducing human workers.

However, not all physical work is equally vulnerable to automation. Some trades are particularly resistant to robotic replacement, at least in the near to medium term.

Skilled Trades: Relative Safety from Automation

One of the best career moves in the face of AI advancement may be entering skilled trades like electrical work or plumbing. These jobs are remarkably hard to automate because they require physical dexterity, problem-solving in unpredictable environments, and adaptation to unique situations. To automate a skilled tradesperson would require something like C3PO from Star Wars—a very advanced humanoid robot capable of navigating diverse physical spaces, manipulating tools with precision, and adapting to unexpected conditions.

Such advanced robotics are quite a ways off. While we might develop AI that can diagnose legal problems or write software code relatively soon, creating robots that can rewire a house or fix a leak in a cramped basement remains a much more distant prospect. This makes skilled trades an attractive career path for those concerned about AI displacement.

Timeline and Pace of Transformation

The rate of AI advancement is rapid, and predictions become difficult because the landscape can change completely in just four or five years. A college freshman choosing a major today faces an uncertain job market by graduation. This accelerating pace makes long-term career planning particularly challenging.

The discussion emphasizes that massive economic and social disruption is likely to occur long before any existential doomsday scenarios. While some worry about AI potentially wiping out humanity, more immediate concerns about job displacement and economic upheaval will manifest first. These near-term challenges require urgent attention and policy responses.

Technology advancement doesn't guarantee that resulting jobs will be better. Society needs focused discussion about which jobs and tasks machines will replace and how we feel about those changes. The technology itself is neither inherently good nor bad; the outcomes depend on how we choose to deploy it and manage its impacts.

Social Cohesion and Distributional Challenges

The Distribution Problem: Who Benefits?

A central concern is ensuring that AI's benefits don't accrue only to a small group of Silicon Valley elites or technology company executives. The distributional question—how to ensure benefits reach everyone rather than concentrating among a few—represents one of the most critical challenges facing society.

The goal should be mitigating downsides while making upsides better for as many people as possible, not just a narrow segment of the population. This requires intentional policy design and social structures that don't currently exist in their necessary form.

Erosion of Trust and Social Fabric

One perspective identifies the loss of social cohesion as potentially more concerning than job loss itself. Already, society shows signs of fragmentation, with declining trust in each other, government institutions, and professional experts like doctors. We have vaccines that cure diseases like measles, yet people fear getting them. This illustrates how even with technological solutions, a fractured society may fail to adopt them.

If people retreat into silos of mutual aggression and suspicion, this could erode all of AI's potential benefits. We might develop incredible medical breakthroughs but fail to use them because communities don't trust the medical profession or scientific establishment. We could create tools to improve living standards dramatically, but if society lacks cohesion, these improvements might go unused or be distributed so unequally that they increase rather than decrease social tensions.

This social dimension represents an underappreciated risk. The technological capabilities matter less if social trust and cooperation deteriorate to the point where society cannot collectively benefit from innovations. The interaction between AI development and existing social trends toward polarization and distrust could prove more dangerous than the technology itself.

The Future Role of Education

Questioning the Value of College

Prominent figures in technology are challenging traditional education paths. Sam Altman has expressed envy of Generation Z college dropouts because they have mental space to build startups. Peter Thiel has propagated growing skepticism about whether college degrees are worth the time and money invested. These perspectives raise important questions about education's role in an AI-driven economy.

Young people increasingly ask, "What's the point of college?" This questioning reflects both the high cost of higher education and uncertainty about whether traditional degrees will remain valuable when AI can perform many tasks currently requiring advanced education.

Shift from Vocational to Liberal Arts Education

Looking toward a future where fewer traditional jobs exist, the intensely vocational bent of higher education may shift back toward general liberal arts education. Rather than focusing narrowly on getting a job in a specific area, education could focus on making people better citizens, more broadly and flexibly educated individuals, and stronger critical thinkers.

This represents a potentially positive development if society can keep people motivated to continue learning. Education should teach people how to think, how to be good citizens, and how to be active lifelong learners, rather than simply preparing them for specific job functions. The challenge lies in maintaining motivation when the connection between education and employment becomes less direct.

There's explicit rejection of the purely vocational question: "What kind of job am I going to get from this education?" Education's purpose extends beyond immediate employment to developing thinking skills and learning capacity that serve individuals throughout their lives, especially in a rapidly changing world.

Paying People to Stay in School

One suggestion involves potentially paying people to remain in educational settings. As job opportunities contract and traditional employment becomes less available, keeping people engaged in learning could serve multiple purposes: personal development, skill building for an uncertain future, and providing structure and purpose during an economic transition.

However, significant questions remain about motivation and goals. What are people doing in school? What are they trying to accomplish? What drives them if not immediate career preparation? These represent unanswered challenges that both universities and society must address.

AI's Impact on Educational Integrity

Education itself is undergoing profound shifts because AI can complete assignments. When students use AI to cheat, traditional forms of education become meaningless. Schools, universities, and educators are trying to figure out how to adapt to this reality. The challenge is redesigning education so it remains valuable and authentic in an age where AI can generate essays, solve problems, and complete most traditional homework.

This adaptation must happen both at institutional levels—how universities structure learning—and at societal levels—how we think about education's purpose and value.

Explosion of Alternative Education Models

The expectation is that alternatives to traditional four-year colleges will proliferate. Online degrees and programs involving AI tutoring people will emerge as potentially reasonable alternatives to conventional university education. Some of these may rise to the point where they offer genuine alternatives to traditional degrees.

This diversification of educational pathways could democratize access to knowledge and skills, though questions remain about quality, recognition, and whether these alternatives will truly provide equivalent value to traditional education.

Career Advice for Young People

Should Students Still Attend College?

Despite uncertainties about education's value, the advice remains that college is still worthwhile. However, the focus should be less on specific majors and more on the kinds of skills students develop. What matters isn't necessarily the particular subject studied, but rather the capabilities and ways of thinking students acquire.

Valuable Skills and Disciplines

Understanding people emerges as one of the most valuable skills in an AI-driven future. Psychology therefore represents a discipline where students can never go wrong. Since human interaction and emotional intelligence are areas where AI struggles, these skills become increasingly valuable.

Economics also offers valuable preparation because it provides an analytical framework for thinking about how people make choices. This systematic thinking about human behavior and decision-making complements pure human understanding with structured analysis.

Working with people, team building, and collaborative skills should be emphasized because these are areas where AI is not yet good—and may not be for some time. Jobs requiring genuine human connection and interpersonal dynamics will be more resistant to automation.

The Importance of Creativity

Creativity represents another critical area for development. Throughout history, when technology has made societies richer, those societies found more money to pay for art and creative expression. This pattern suggests significant space for creativity in the future economy.

Students should build out their creative sides. Musical theater, visual arts, and other creative pursuits represent valuable areas of study. Even if one perspective jokes about this meaning entertaining wealthy people, the underlying point is serious: creative work that requires genuine human insight and expression will remain valuable.

Genuine creativity—not just pattern recognition or recombination, but true creative insight—is very hard for AI to replicate, at least currently. This makes it a valuable area for human specialization.

Core Skills Over Specific Majors

The consensus is that focusing on core skills and talents matters more than the specific major chosen. Given how rapidly the landscape changes, attempting to predict which specific field will be valuable in four or five years is nearly impossible. A college freshman's major today might prepare them for a job market that looks completely different by graduation.

Therefore, the emphasis should be on developing flexible capabilities: critical thinking, problem-solving, working with people, creative expression, and the ability to learn and adapt. These meta-skills will serve students regardless of how the specific job market evolves.

The Optimistic Case: AI as Tool for Human Amplification

Despite concerns, there's significant optimism about AI's potential. Both perspectives in this discussion agree that AI will be the most powerful tool humanity has ever had to amplify our intelligence and creativity. This amplification should allow enormous progress across numerous domains.

Scientific fields stand to benefit dramatically. Medical research, in particular, could see breakthrough after breakthrough as AI helps researchers analyze complex biological systems, identify drug candidates, and understand disease mechanisms. The potential for curing diseases, extending lifespans, and improving health outcomes is substantial.

Technology development itself will accelerate as AI assists in engineering, materials science, energy research, and countless other fields. Living standards could improve dramatically if AI helps solve problems of energy efficiency, resource management, and production optimization.

The fundamental promise is that AI should, in the long run, make everyone better off. However, realizing this optimistic scenario requires successfully navigating the transition period and solving the distributional challenges. The benefits won't automatically flow to everyone; intentional effort is needed to ensure broad-based improvements in human welfare.

Looking Ten Years Ahead: Hopes and Fears

Primary Economic Concerns

Looking forward, the greatest worry from the pessimistic perspective centers on economic impact rather than existential risk. While doomsday scenarios where AI wipes out humanity might someday be real concerns, massive economic and social disruption will arrive long before any such scenarios materialize.

This disruption could manifest through job automation, as discussed extensively, but also through the bursting of the AI investment bubble, which could be devastating to the broader economy. Over the next ten years or so, these represent the two big fears that could materialize.

The Danger of People Being Left Behind

There's genuine fear that some people will be left behind during the next decade. Not everyone will successfully navigate the transition to an AI-driven economy. Some workers will struggle to find new roles, some regions will lose major industries, and some communities will face economic devastation.

However, one perspective argues that the bigger fear isn't job loss per se, but the loss of social cohesion. Social fragmentation is already underway, and its acceleration could prove more damaging than employment challenges. If society lacks trust and cooperation, even beneficial technologies won't improve collective welfare.

What Success Looks Like

The optimistic vision ten years hence involves AI delivering on its promise as an amplification tool. Medical breakthroughs would improve health and longevity. Scientific advances would address climate change, energy needs, and resource constraints. Productivity improvements would raise living standards.

Critically, these benefits would be distributed broadly rather than concentrating among a wealthy elite. Society would successfully manage the employment transition through some combination of new job creation, education adaptation, social support systems, and possibly new economic models that don't require everyone to work traditional jobs.

Social cohesion would be maintained or restored, allowing communities to trust institutions, trust each other, and collectively benefit from technological advances. Education would successfully adapt to prepare people for meaningful lives in an AI-augmented world.

The Path Forward

Ultimately, both perspectives agree that society must figure out how to adapt to AI's dangers while ensuring benefits reach everyone. This requires active management rather than assuming positive outcomes will automatically emerge. Policy makers, businesses, educational institutions, and civil society all have roles to play.

The conversation makes clear that neither technological determinism nor pure optimism is appropriate. AI presents genuine risks alongside enormous opportunities. The challenge is navigating between unrealistic pessimism that ignores potential benefits and naive optimism that downplays real dangers.

Success requires acknowledging that transformation takes time, that pain during transitions is real and must be addressed, that distributional questions cannot be ignored, and that social cohesion matters as much as technological capability. These lessons from history and economic analysis should guide how society approaches the AI revolution.

Fundamental Questions Requiring Answers

This discussion raises but doesn't fully resolve several critical questions that society must grapple with:

- How do we maintain human dignity and purpose in an economy where traditional employment may not be available to everyone?

- What economic structures can ensure AI's benefits are distributed broadly rather than concentrating wealth further?

- How can education systems adapt to remain relevant when AI can complete most traditional assignments and assessments?

- What policies can help workers transition from displaced jobs to new opportunities without suffering devastating economic hardship?

- How do we prevent or reverse the erosion of social trust that threatens to undermine collective benefits from technology?

- What distinguishes human capabilities that should be preserved and cultivated versus tasks that should be handed to AI?

- How quickly will different sectors and job categories face AI disruption, and can we predict this well enough to prepare?

- What role should government play in managing AI's economic impacts versus leaving adaptation to market forces?

These questions don't have easy answers, but addressing them thoughtfully will determine whether AI becomes a force for broad-based human flourishing or a source of economic disruption and social fragmentation. The technology itself is neither inherently beneficial nor harmful—the outcomes depend entirely on the choices society makes in deploying it and managing its consequences.